Stand-up comedy tends to work best when people have paid to watch it. If you run a comedy night in a pub and let people come in for free, people don’t come especially to see it, they just wander in randomly. Rather than entertainment, the stand-up becomes little more than an unwelcome interruption to a quiet night out. If people don’t want to laugh they won’t laugh, even if the comedians are really good.

Stand-up comedy tends to work best when people have paid to watch it. If you run a comedy night in a pub and let people come in for free, people don’t come especially to see it, they just wander in randomly. Rather than entertainment, the stand-up becomes little more than an unwelcome interruption to a quiet night out. If people don’t want to laugh they won’t laugh, even if the comedians are really good.

This makes stand-up at festivals a potential problem. The people who wander into the tent where it’s taking place are just generalised fun-seekers rather than punters who are actively seeking a good laugh. The comedy I programmed at the Playhouse at Lounge on the Farm last Friday night was exactly like that. People wandered in and out throughout the three hours of the show, and they were as likely to lie flat out on the rugs strewn over the grass as sit on the bales of hay provided for seating.

In this atmosphere, it’s near-impossible to establish the essential call-and-response rhythm of joke-laughter which stand-up relies on. The comedians are all ex-students from the stand-up course I teach as part of the drama degree at the University of Kent, and although they’ve all got at least twenty shows under their belts, I’m worried that they might not be able to adapt to this strangely spaced-out audience.

In fact, the show is fine. The audience response is ragged but respectable – a few solid but diffuse laughs followed by a quite patch, an isolated laugh from a punter at the back followed by a big laugh with spontaneous applause. Outrageous gags go down well, an obvious example being Carys Williams’ ukulele song about kinky sex. Jokes about the immediate circumstances are also enjoyed, but ask them too many questions and they get tired.

Perhaps my favourite moment is when Liz Page is about to launch into a routine about fellatio, and suddenly notices an angelic child with a mop of blond hair, hugging a red balloon, and staring earnestly up at her. Playing the dilemma brilliantly, Liz points the child out, wonders whether she’ll leave it with permanent emotional scars, then performs the routine by conjuring up appropriate euphemisms. Because we can see the fix she’s got herself into, we share her comic agony, and enjoy the way she wheedles her way out of the situation.

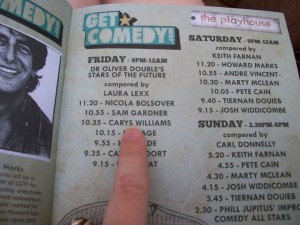

To be fair, the audience’s reaction comes and goes throughout the evening, but that’s no reflection on the comedians’ talent. The very good professional comedians who play the Playhouse the following night and Sunday afternoon get much the same kind of reaction.

To be fair, the audience’s reaction comes and goes throughout the evening, but that’s no reflection on the comedians’ talent. The very good professional comedians who play the Playhouse the following night and Sunday afternoon get much the same kind of reaction.

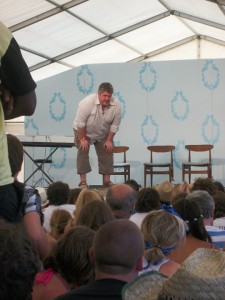

The only exception is the excellent impro comedy show hosted by Phill Jupitus on the Sunday. The tent is simply packed, and there’s a big crowd watching from outside. The difference is that these people have definitely chosen to be here, drawn by Jupitus’s TV fame. Having said that, reputation might have brought them here, but it’s sheer talent that keeps them. Onstage, Jupitus is cheerfully aggressive, ridiculing someone’s hat here and telling someone to fuck off there, yet somehow still coming over as a big softie.

The only exception is the excellent impro comedy show hosted by Phill Jupitus on the Sunday. The tent is simply packed, and there’s a big crowd watching from outside. The difference is that these people have definitely chosen to be here, drawn by Jupitus’s TV fame. Having said that, reputation might have brought them here, but it’s sheer talent that keeps them. Onstage, Jupitus is cheerfully aggressive, ridiculing someone’s hat here and telling someone to fuck off there, yet somehow still coming over as a big softie.

The improvisation is standard fare, but expertly performed – not just by Jupitus, but also by the excellent comics who join him onstage. Richard Vranch proves as able off the keyboard as on, Andy Smart exudes blokey charm even when taking on female roles, and Steve Steen has a rare comic delicacy which defies his short, round frame. While this show is on, the tent is longer holding a weird festival audience – it’s transformed into a genuine comedy gig.