Next week, over 2,700 medievalists will convene at the annual Leeds International Medieval Congress. As usual, several members of the MEMS community will be participating … Read more

Category: News

MEMS Fest 2024 – announcing our new committee

We are delighted to announce our new MEMS Fest 2024 committee who will be running our 10th annual festival on Friday 14th and Saturday 15th … Read more

MEMS celebrates funding success for doctoral scholarships

MEMS is celebrating a significant funding success. In partnership with King’s College London, it has been awarded a prestigious Doctoral Scholarships Programme by the Leverhulme … Read more

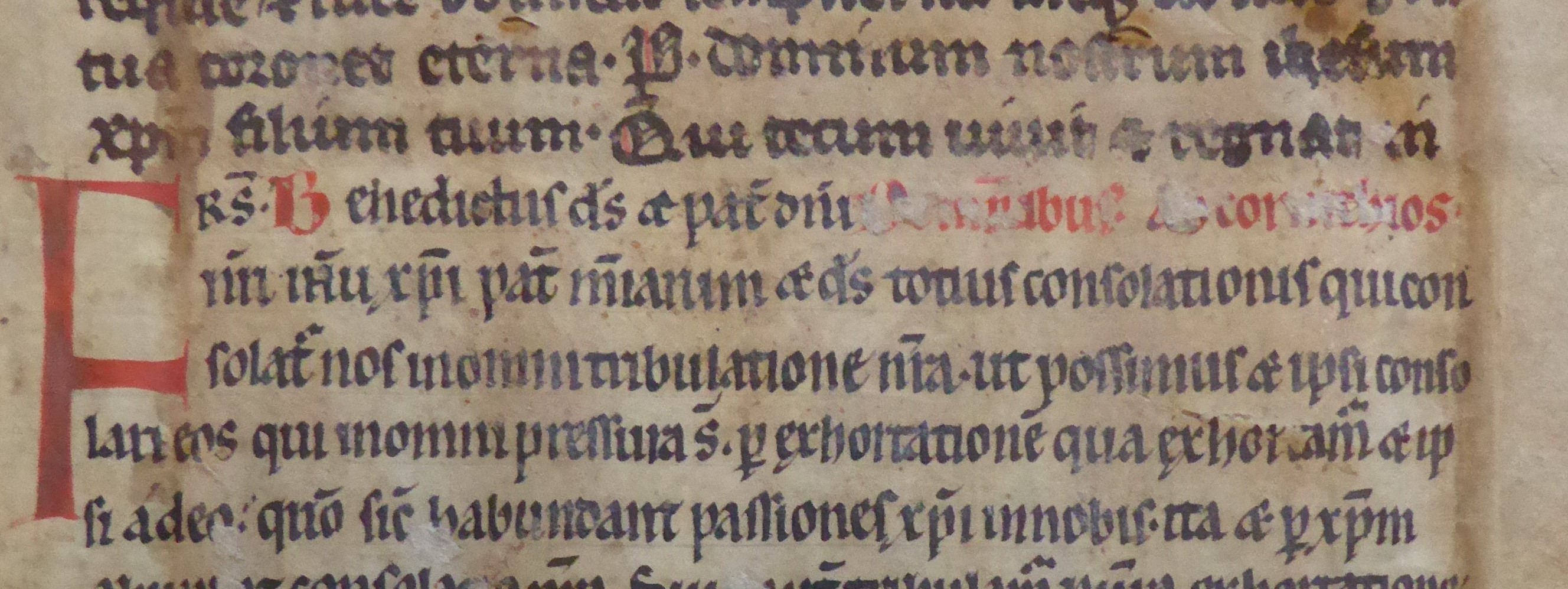

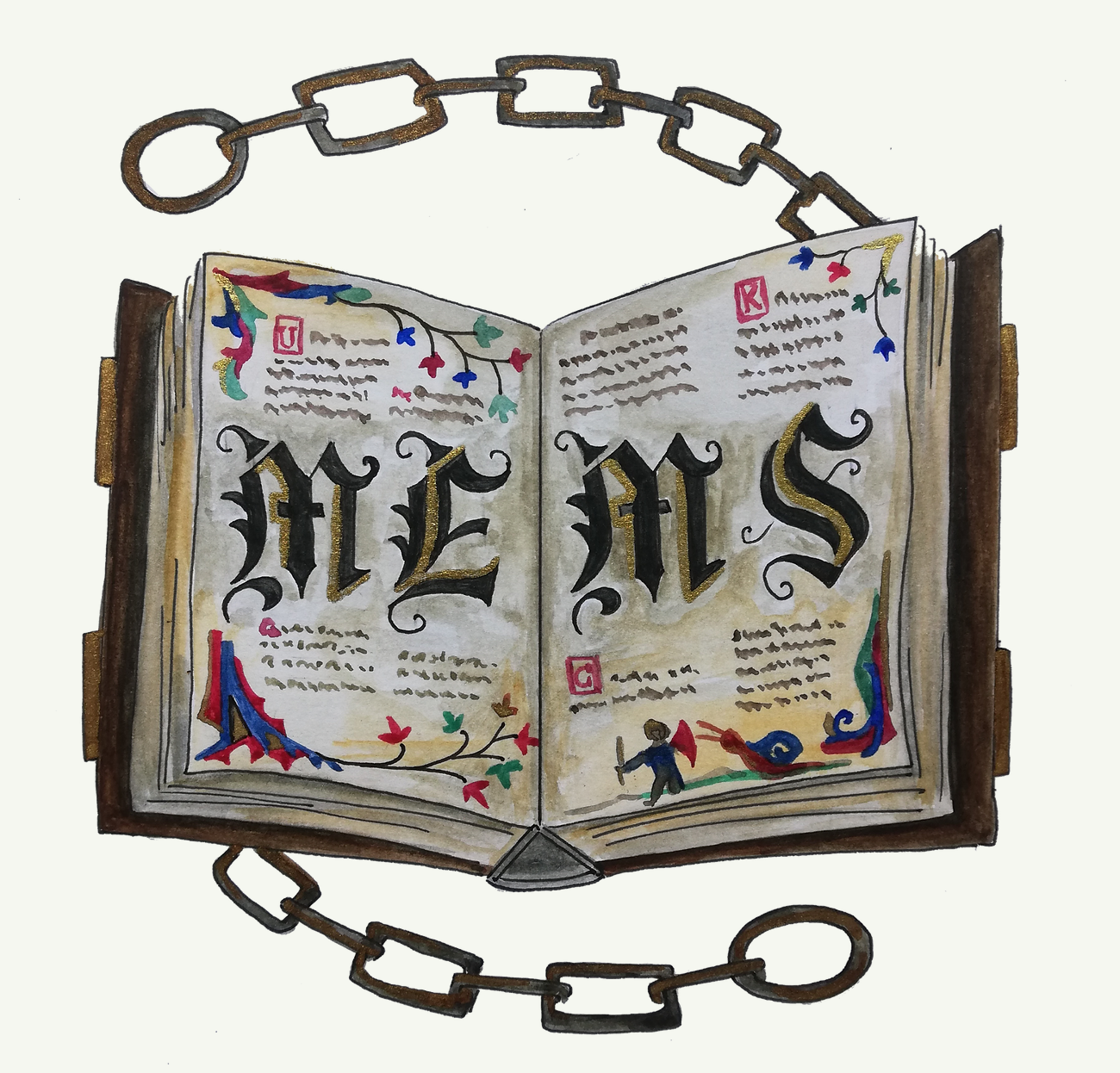

MEMSLib: the new team get to work

We are delighted to introduce the new team responsible for MEMSLib, our award-winning student-led resource project. MEMSLib is a digital library which provides curated listings … Read more

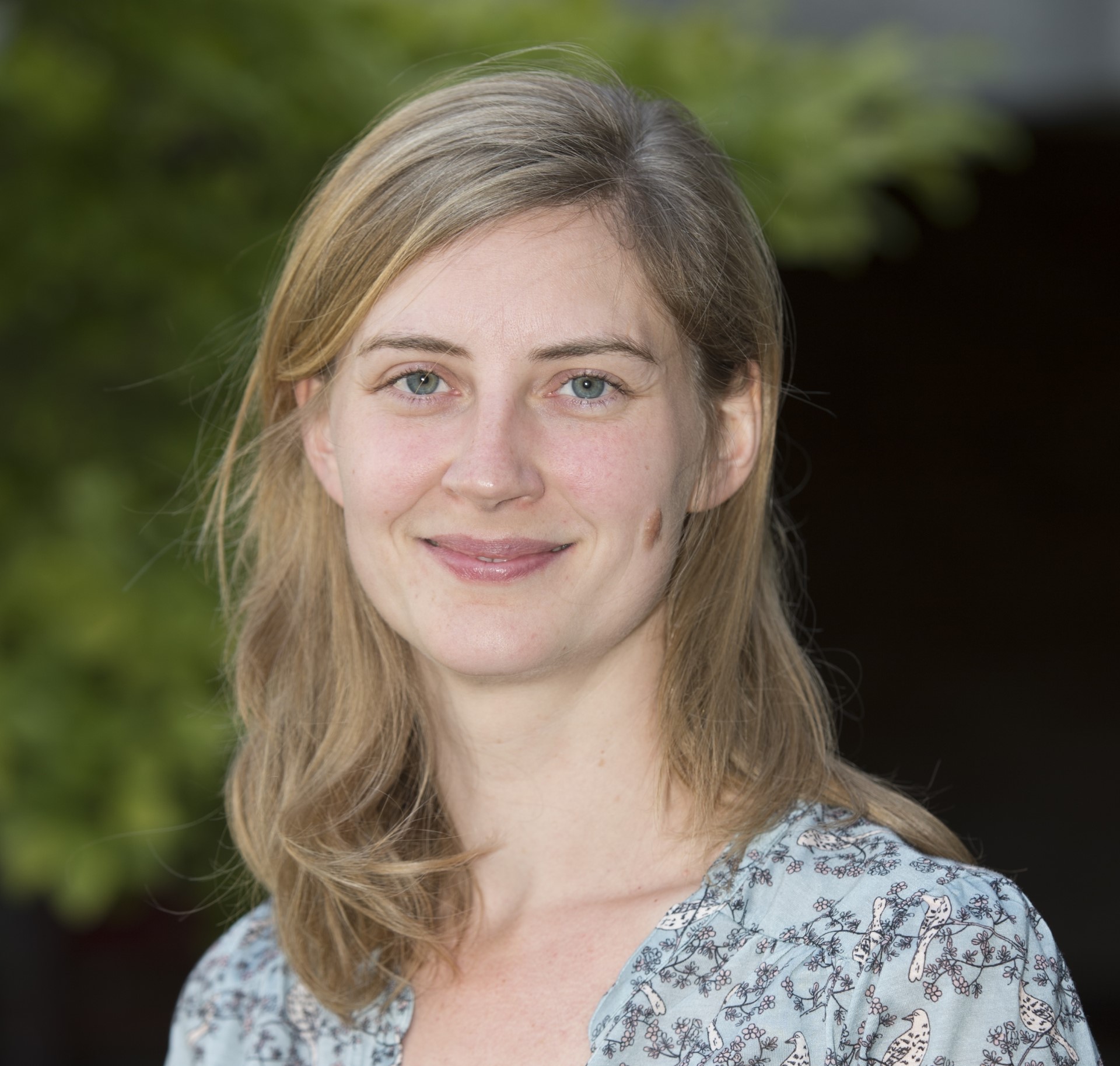

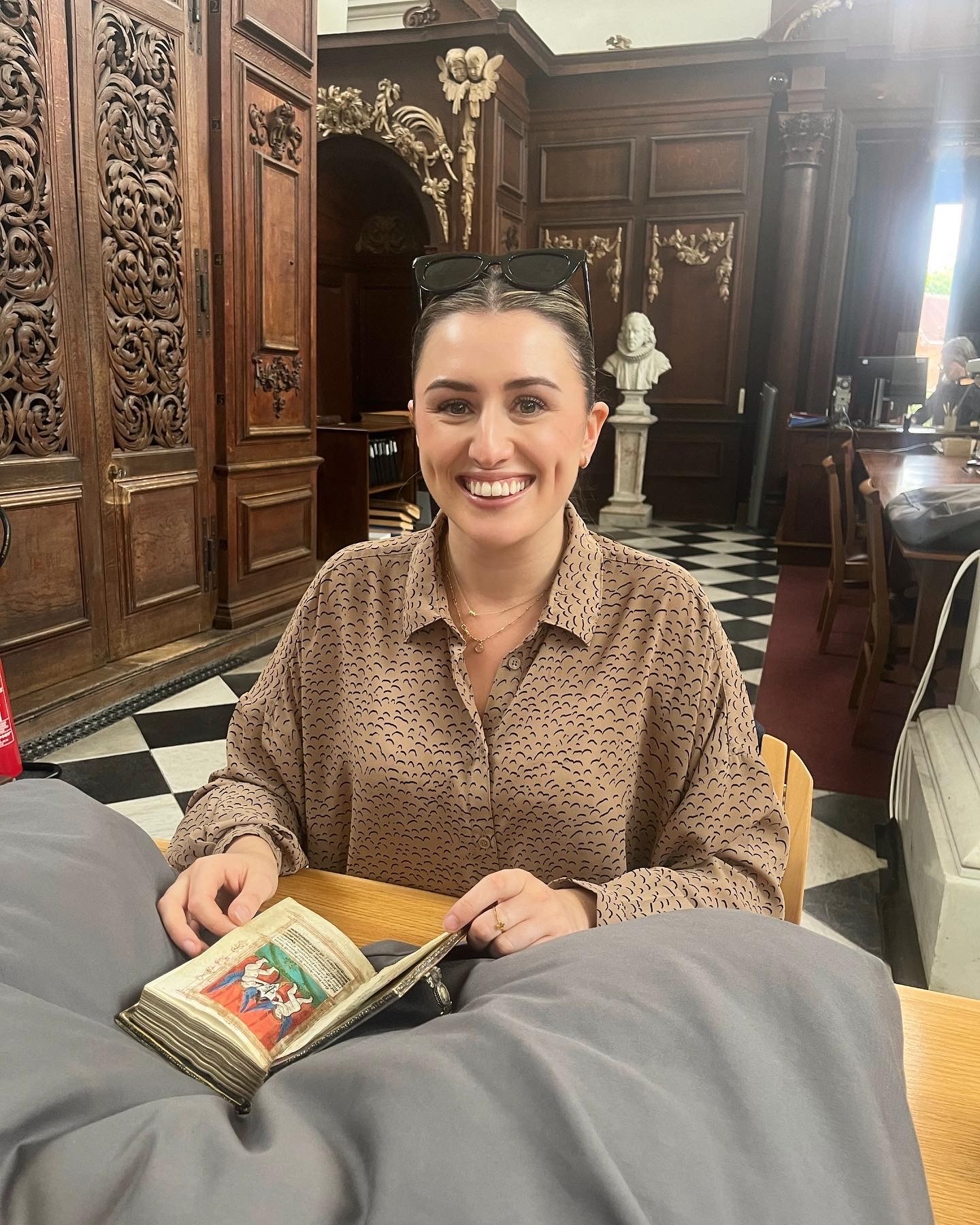

MEMS welcomes new director, Dr Suzanna Ivanic

We are delighted to announce the appointment of a new director of MEMS, Dr Suzanna Ivanic. Suzanna is Senior Lecturer in Early Modern History in … Read more

MEMS art historian on TV again

One of the stars of MEMS can be seen on television, again. Dr Emily Guerry is a medieval art historian and former Co-Director of the … Read more

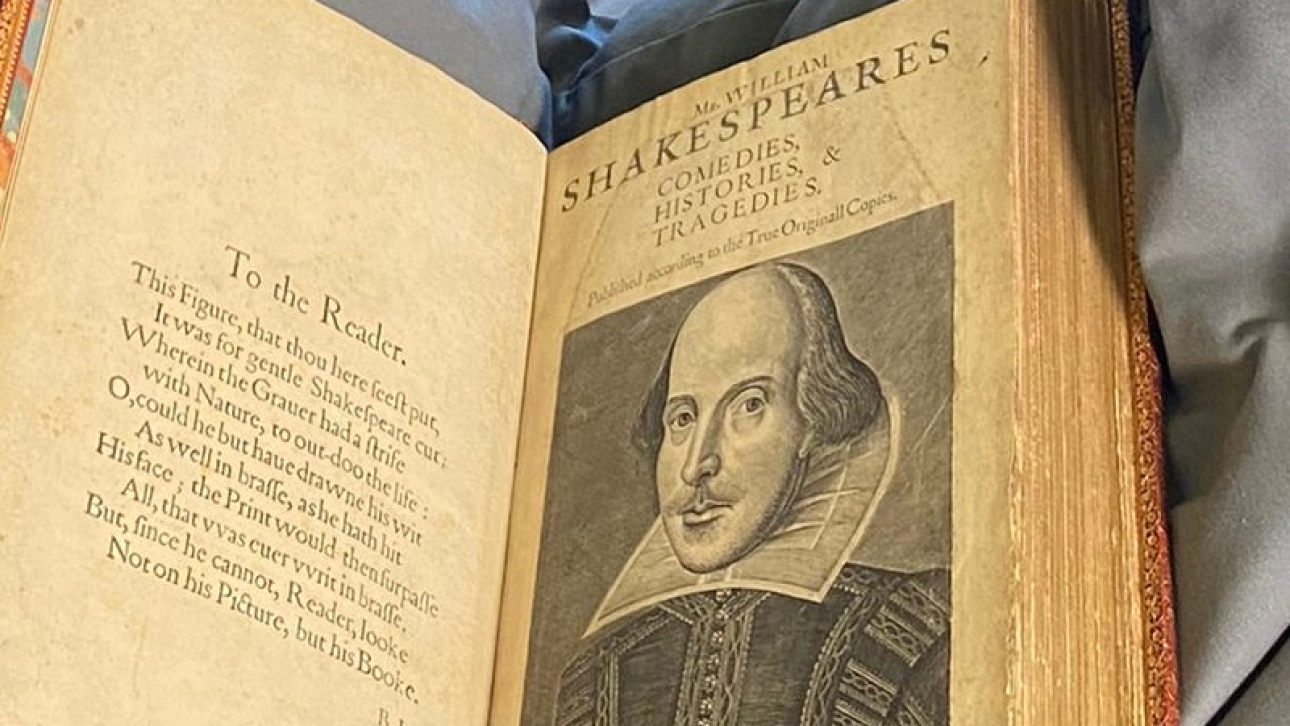

Celebrating Four Hundred Years of Shakespeare’s First Folio

This year marks the quatercentenary of the publication of what is now known as the First Folio of William Shakespeare’s Comedies, Histories, & Tragedies. More … Read more

MEMS alumna in the news again

Graduates of the MEMS MA make good use of their training. An outstanding example of this truth is how the research of Kate McCaffrey has … Read more

Dr Suzanna Ivanič wins the Society for Renaissance Studies Biennial Book Prize 2022

Congratulations to Dr Suzanna Ivanič for winning the Society for Renaissance (SRS) Biennial Book Prize 2022 for Cosmos and Materiality in Early Modern Prague (Oxford: … Read more

Monograph shortlisted for Society for Renaissance Studies book prize

Recognition for research in the Centre for Medieval and Early Modern Studies continues, as Dr Suzanna Ivanic’s monograph Cosmos and Materiality in Early Modern Prague … Read more