Join us in Canterbury and online for the eigth annual MEMS Festival at the University of Kent. We invite abstracts of up to 250 words … Read more

Month: March 2022

MEMS students enjoy exclusive access to three London exhibitions

On Thursday 10 February, 15 MEMS MA and PhD students enjoyed a special field trip to three exciting collections in London, where we were guided … Read more

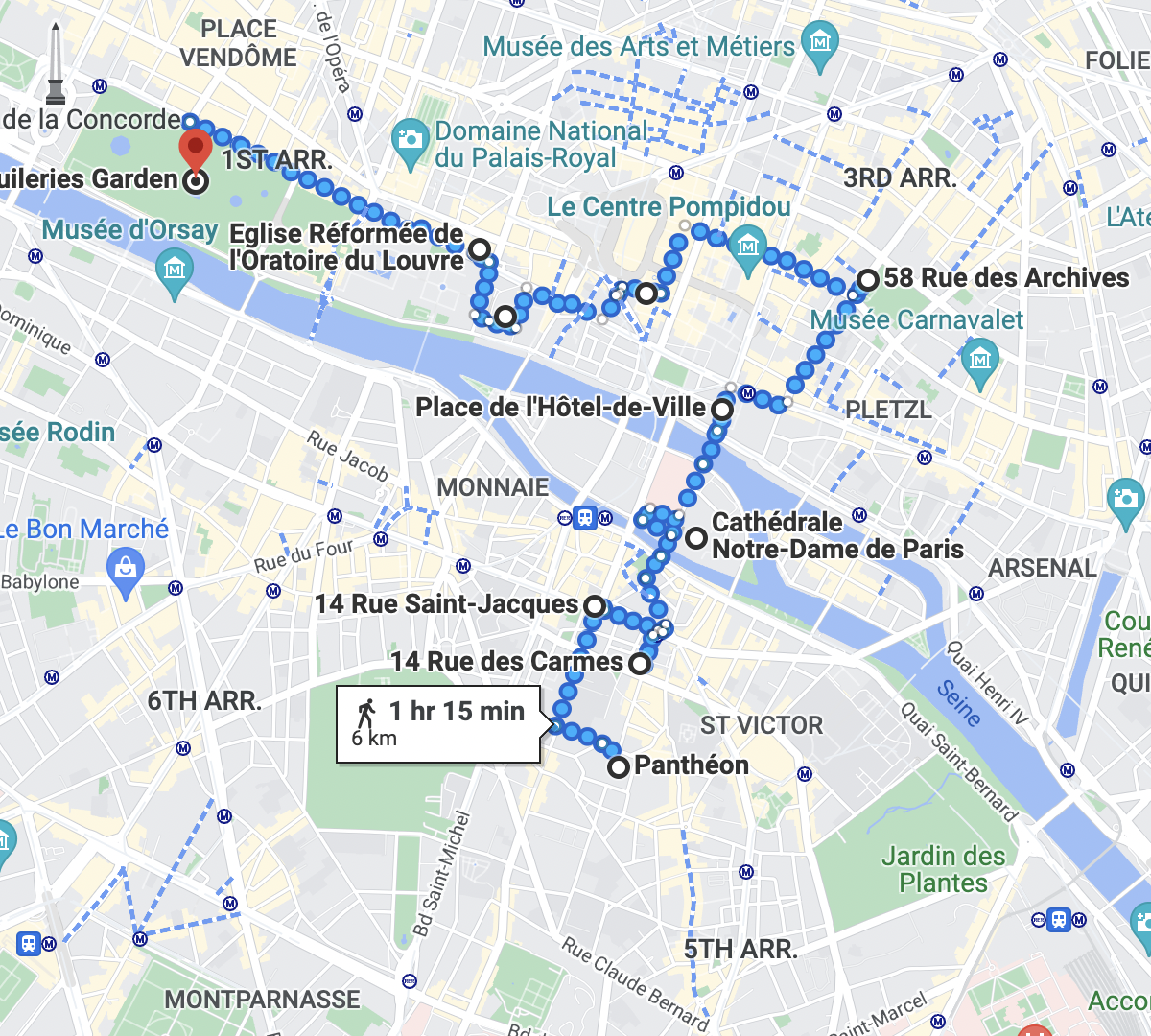

MEMS students take part in special St Bartholomew’s Day Massacre walking tour

By Jessica Falkner, MA student, Centre for Medieval and Early Modern Studies In the early hours of 24 August 1572, the Saint Bartholomew’s Day Massacre … Read more