Posted by Sarah

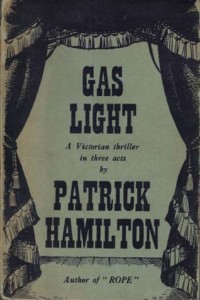

Discussion of Gaslight began with similarities and differences between the UK and US versions which allowed the analysis of melodrama at a very specific textual level; this included comments on characterisation, plotting, direction and performance; we also spoke about Guy Barefoot’s piece which compared the two films and the original play. Do log in to leave your comments, or email me on sp458@kent.ac.uk.

The largest part of our discussion focused on similarities and differences between the UK (1940, Thorold Dickinson) and US (1944, George Cukor) versions. Changes to the names of the two main protagonists were immediately obvious: Bella Mallen (Diana Wynyard) becomes Paula Alquist (Ingrid Bergman) while Paul Mallen (Anton Walbrook) is Gregory Anton (Charles Boyer) in the later version. Character changes also occurred at a less surface level. The concerned cousin Vincent Ullswater (Robert Newton) and determined ex-policeman B.G. Rough (Frank Pettingell, providing much of the film’s comic relief) of the UK version are amalgamated into the detective Brian Cameron, played by Joseph Cotten in the Hollywood film. The comedy function of Rough’s ex-policeman is displaced onto nosy neighbour Miss Thwaites (Dame May Whitty) in Cukor’s version. This allows for the Hollywood film to retain some of its British flavour with the employment of the well-known British character actress.

The creation of the Brian Cameron character was thought to be connected to Hollywood’s concern with portraying romantic relationships. Cotten’s character is younger than Pettingell’s, and provides a potential love interest for Paula. Hollywood’s focus on romance was also thought to be a reason for the fact Cukor’s film spends a fair bit of time recounting the courtship of the married couple, while the British film does not. Dickinson’s film begins with the murder of the aunt, and then skips forward to the arrival of the married couple twenty years later.

Characters’ motivations were felt to be less convincing in the earlier film. The victim is the husband’s elderly Aunt rather than the wife’s younger more glamorous aunt. This meant that the husband has less reason to drive his wife mad. Bella also seemed to be more easily victimised – when asked to betray her husband she stated the fact that he had already betrayed her was ‘different’ – while Paula was more willing to stand her ground. This was noted especially as in the Hollywood version the heroine suffers doubly: she loses not just her husband’s love and very nearly her mind, but also her beloved Aunt. This difference in the heroines’ behaviour might have been because of the shifts in ambiguity. In the earlier film the husband’s menacing behaviour was quickly established while the 1944 version kept us guessing for a lot longer. The ambiguity in Dickinson’s film lay in Bella’s character at the very end. Bergman played the scene, in which she brandishes a knife at her tied up husband and states she is not doing so, in the certainty we knew that she was toying with her husband. However, Wynyard seems very genuinely on the brink of madness. Lingering close up shots of Walbrook’s face led us to wonder if she was indeed going to stab him, or perhaps even cut him free.

Cukor’s film was more insidious, driven by psychology, any included many stylistic flourishes. The later film included several shadowy and painstakingly composed shots. The earlier version’s main gestures to style were the superimposition of Bella’s face on her clockwork music box which she starts to drown out the noisy footsteps above her. Also appearing towards the end of the film is the canted frame which coincides with the increased concern with hysteria. Indeed it was noted that while the British version told the story in a straightforward, possibly workmanlike manner, which was more plot driven, the American film appeared more polished, paced, with its elements better integrated. Things were told rather than shown, and if shown done so quickly, in Dickinson’s film, and there was less character evolution.

Arguably the British film’s approach chimes more with melodramatic sensationalism. It is interesting that while the UK film made it onto to our long list of melodramas, the US film did not (http://blogs.kent.ac.uk/melodramaresearchgroup/2013/03/03/unmissable-melodramas-the-long-list/ ). The Hollywood version’s genre is described as mystery, its subgenre psychological by the American Film Institute Catalog: http://www.afi.com/members/catalog/DetailView.aspx?s=&Movie=1552. Are these differences between the two films therefore related to what melodrama is (its relationship to the sensational) and what it is not? Or should both (or neither!) films be considered melodramas. Does the fact that Bergman’s character arguably experiences more suffering than Wynyard’s qualify the Hollywood version as melodrama?

Although the British film was much shorter and seemed more direct, there were some scenes which seemed unnecessary in terms of plot. There is a fairly long scene in which higher class children play in the park, while street urchins are seen outside the gates. As well as pointing to Bella’s childless status, and thereby linking her hysteria more closely to her gender, this comments on the British pre-occupation with issues of class. This was also the case for the extended musical hall visit in which the husband and the maid, Nancy, sat in the balcony with the hoi polloi below them in the stalls. This may well have also been a gesture to the film’s stage origins.

Guy Barefoot’s piece on the recreation of the Victorian in the twentieth century prompted some interesting discussion. This was largely related to melodrama more broadly. We considered the apparent contradiction between the resurgence of melodrama, and the recreation of the Victorian era, and the fact this was on the whole negative: the period was one of ‘darkness and fear’ (p. 95). Barefoot’s quoting of Christine Gledhill’s assertion that melodrama became more popular in America than Europe (p. 95 from Home is Where the Heart Is BFI, 1994, p. 25) and the fact that a return to the Victorian and to melodrama occurred in the 1940s (p. 101)(well-represented by the success of Gas Light in the theatre and on the screen) were also useful. These led us to ponder just when and where melodrama was popular, both in the theatre and the cinema and what insights such knowledge would provide.