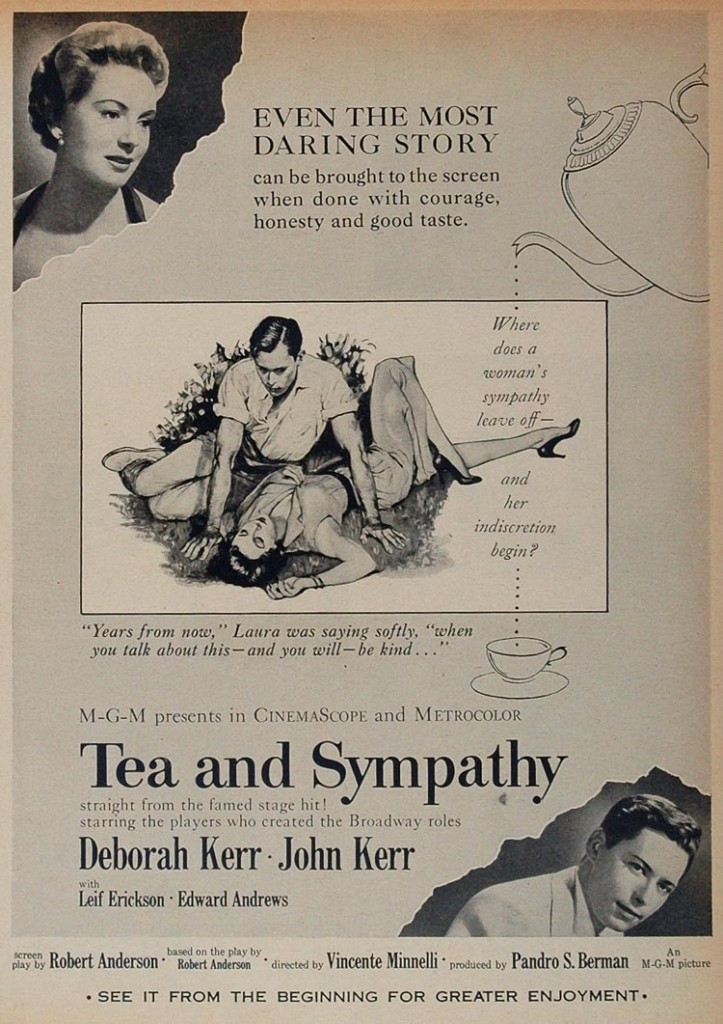

Above: A poster advertising Vincent Minnelli’s Tea and Sympathy (1956)

A still from Vincent Minnelli’s Tea and Sympathy (1956)

20th November 2012, GLT3 5.30pm

Dr Gary Needham, Nottingham Trent University

Revisiting Tea and Sympathy (1956): Minnelli, Hollywood, Homosexuality

Despite never once mentioning the word homosexuality, Tea and Sympathy nonetheless seems to say a lot about homosexuality in the 1950s. An effete young man, nicknamed ‘Sister Boy’ by his Fraternity, struggles with his unmanly ways only to be rescued by an older woman, the housemaster’s wife played by Deborah Kerr, who commits a sacrificial act of adultery in order to ‘cure’ his masculinity of its feminine ills. She tells him in the play/film’s most famous line: ‘Years from now when you talk about this, and you will, be kind’.

A minor, often forgotten work of Vincent Minnelli and 1950s Hollywood, Tea and Sympathy is known as a risible film that is often flagged up as key example of Hollywood’s disservice to homosexuality: it features heavily in The Celluloid Closet. Based on a successful Broadway play and released at the height of the ‘Lavender Scare’, Tea and Sympathy has been used in many an argument to illustrate a range of problematic assumptions, representations, and ideas around homosexuality and the regulatory and apparently regressive nature of Hollywood. Tea and Sympathy does confirm and conform to a number of these arguments, it caused trouble at MGM and is unquestionably problematic yet, as I will explore in this paper, there seems to something more complex and subtle going on in Tea and Sympathy: the simple misery it narrates is often contradicted by the mise en scene. Minnelli makes reference through film style to other closeted artists working in a mire of contradictions, for example, J. C. Leyendecker, central to the production of representations of American masculinity. Furthermore, a number of key scenes (‘beefcake on the beach’ and ‘fraternity pyjama fight’ mainly) tell us a good deal about the relationship between homosociality, homoeroticism, and Hollywood and the contradictions inherent in ideas that 1950s homosexuality was only visible and knowable as gender inversion.