One of the great pleasures involved in working on the Lady’s Magazine is talking to people about it. I love surprising people with its diverse contents and am yet to find a subject (from the reception of Dryden to recipes for the cure of various skin disorders) about which it does not say something interesting across the course of its long run. (Keep testing me, people!)

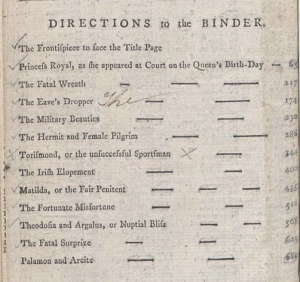

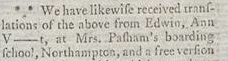

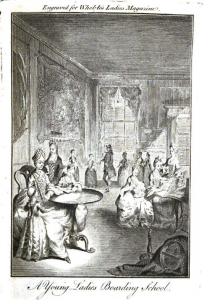

Frontispiece to LM IV (1773). Image © Adam Matthew Digital / Birmingham Central Library. Not to be reproduced without permission.

But while it is very easy to say what is in the Lady’s Magazine, characterising what it is really about is much harder. In part, this is because every time you think you have hit upon the thing that holds the periodical together (fashion, class, morals or women’s issues – whatever they might be) you read something that throws you completely. This is, in part, because the multi-authored, multi-vocal format means that the only consistent thing about the magazine is its inconsistency. Even when a contribution is not in active dialogue with another it buffets up against the articles it appears alongside, creating a range of possible meanings only some of which could have been in the control of the magazine’s editors.

I plan to say more about the production of meaning and ways of reading the magazine in future posts. Here, though, I just want to focus briefly on one of the many consistent inconsistencies of the magazine: its attitude to boarding schools. It’s a subject I have become increasingly fascinated by, not least because it speaks to one of the key things that I now am coming to think holds the magazine together: the question of women’s education.

Koenraad has already noted on the blog that a small but significant number of Lady’s Magazine contributors (particularly of enigmas, rebuses and translations in response to the monthly translation competitions that ran in the magazine’s early years) were boys and girls. We know this because their age sometimes appears alongside their contributions or because they are accompanied by the name of the school they attended.

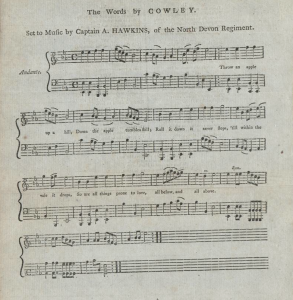

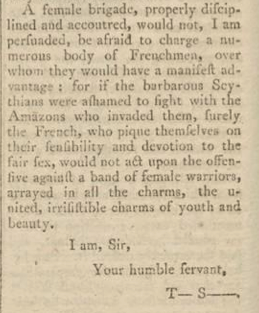

LM, IV (May 1773): 23. Image © Adam Matthew Digital / Birmingham Central Library. Not to be reproduced without permission.

Pupils wore the name of their school alongside their signatures like a badge of honour. Meanwhile, the ubiquity with which the names of establishments such as Mrs Pasham’s boarding school, Northampton, Pimlico boarding school, or Brown and Reynolds’s school in Stepney, appear seems to suggest that headmasters and governesses saw their pupils sending in contributions to the magazine as an effective (and cheap) form of advertising.

It was a game that the magazine was not only willing to play but of which its editors recognised the necessity. As they acknowledged on many occasions, boarding schools were a potentially large market for their periodical, and being put on school library shelves was important for the magazine’s continued success. This was not just a matter of securing subscriptions, as the editors made clear in the ‘To our Correspondents’ column in the September 1775 issue. After boasting of the ‘infinite pleasure’ they had in acknowledging ‘the receipt of hints from the most celebrated boarding schools in six counties, during the course of th[e] month’, the editors went on to ricochet flattery back and forth between its boarding school patrons and itself. If ‘the governesses of these seminaries are the best judges of what will contribute to the amusement, polishing, and refinement of their pupils’ then their approval of the magazine could not better convince the magazine’s editors of ‘our own importance, at the same time as we shall receive an incontrovertible proof of their sincere attachment to the good of the younger part of the sex, who have the benefit of their instructions’ (LM VI [Sept. 1776]: n. p.).

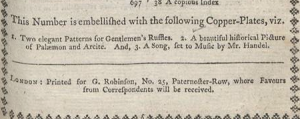

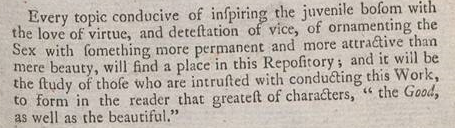

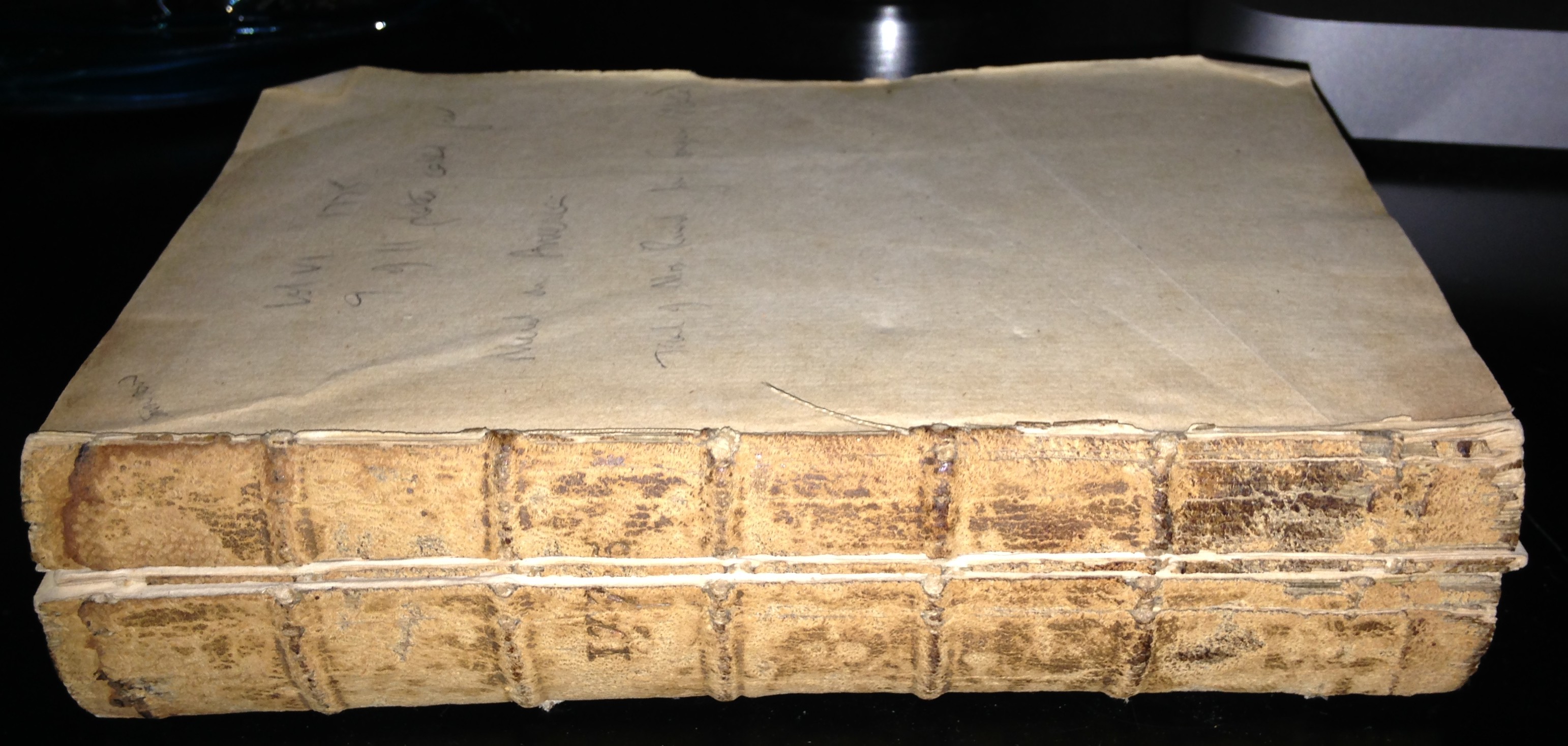

LM II (Sept 1771). Image owned by the author.

But the esteem was not always mutual. In September 1785, for instance, a correspondent who went by Modestia wrote to the magazine’s agony aunt, Martha Gray (aka The Matron), to complain about the periodical’s publication of one of its resident physician, Dr Turnbull’s, columns on male midwifery. The issue at stake was not exactly the content of the column, but its availability to young readers ‘of both sexes’. If the magazine were ‘only to be locked up in our closets with our family medicines the discussion of such subjects might be allowable’, Modestia admitted. Given, however, that it was ‘extensively perused by young ladies at their boarding schools’, it could be ‘productive of awkward situations’. The ’embarrass[ment]’ of ‘the governess’ when posed with difficult questions arising from such content is offered up as the principal source of Modestia’s unease, but she closes, somewhat elliptically, by noting that young boarding school misses are at precisely ‘that time of life when novelty strikes us in the most forcible manner, and puts our ideas into motion’. The Matron politely brushed aside Modestia’s complaint (and completely ignores her implicit suggestion that such material might make young girls sexually inquisitive or even sexually active) by noting that precisely the same impressionability her correspondent fears ensures that young girls ‘may be easily diverted from such subjects, which they cannot understand, and turned to others more suitable to their age, and more adapted to their comprehension’ (XVI: 472). If the compliments of boarding school mistresses were gladly accepted and publicised, their complaints were hardly taken seriously.

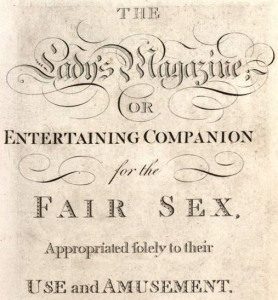

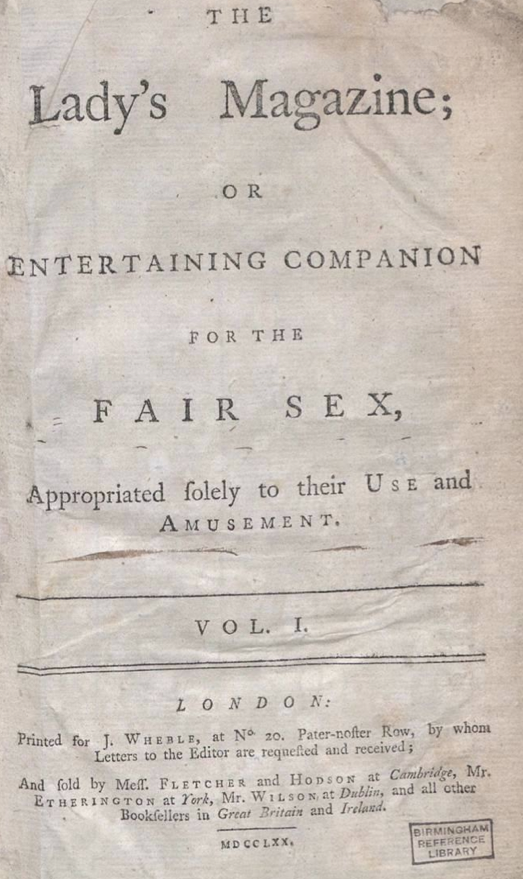

LM, I (1770). Image © Adam Matthew Digital / Birmingham Central Library. Not to be reproduced without permission.

For its part, however, the magazine would regularly caution against fashionable boarding school education and the vices of socially ambitious governesses. One such example will already be familiar to readers of this blog. In December Jenny wrote about the anonymous serial fiction, ‘The History of an Humble Friend’, which ran from September 1774 to the Supplement (or thirteenth issue) of 1776. The titular heroine, Harriot West, is sent to a boarding school at the age of five, and although her governess is kind and good (unlike many others who appear in the magazine’s pages), Harriot’s fellow pupils are no advertisement for boarding school education. Sent to such establishments by mothers who are unfit for the name so that ‘they may not provoke their jealousy at home’, these girls are given an opportunity to ‘acquire more knowledge than they would have done at home’. However, this is an opportunity that is squandered owing to the girls’ interaction with other young girls whose fashionable vices they invariably contract and in the face of which governesses are powerless: ‘At home, they [these pupils] have, perhaps, only their own failings to subdue, at school, they are, by associating with young folks of different follies, too apt, from the force of imitation, to copy the very imperfections against which they they ought to be the most strongly guarded’. Knowing how reliant the magazine was on the very approval of the establishments their contributor had slighted, the editors published this instalment of the fiction with a note at the bottom of the page which stated that ‘these remarks on Boarding-Schools’ were inserted ‘ to shew our impartiality, but [we] differ from the author in opinion’ (LM V [Oct. 1774]: 521). There is plenty of evidence elsewhere to suggest that the editors are protesting a little too much here.

But where does this leave us? What does the magazine’s inconsistent account of boarding school education tell us except that the magazine contradicts itself on this as on so many other matters? Well, for one thing, it makes clear, I think, how the magazine’s ideological fault lines and the complexity of its relationship with its readers were informed by economic imperatives (nothing new under the sun, as they say…). More than that, though, I think, it points to the one thing that I feel totally comfortable saying the magazine is actually about: not fashion, class, morals, education or women’s issues, although it it is surely about all of these things, but conversation. As Modestia unwittingly noted, the Lady’s Magazine’s business was putting ‘ideas into motion’. Sometimes these ideas gained momentum and a life of their own and sometimes they collided messily. One thing is for sure, the magazine always provoked more questions than it answered. And while that presents certain challenges to those of us who want to talk or write about the magazine, it’s surely what makes the experience of reading it so very seductive.

Dr Jennie Batchelor

School of English

University of Kent

Finding a year that was both particularly interesting in terms of content and in poor enough condition to be affordable took a bit of time, but I finally found a very readable (though almost disbound and missing the front board) volume of the Lady’s Magazine for 1775.

Finding a year that was both particularly interesting in terms of content and in poor enough condition to be affordable took a bit of time, but I finally found a very readable (though almost disbound and missing the front board) volume of the Lady’s Magazine for 1775. There is, of course, that connection to the past that seems so much stronger when handling the same worn and yellowed pages once thumbed through by the eighteenth-century reader.

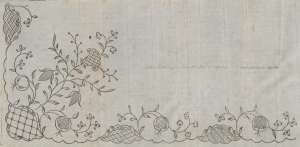

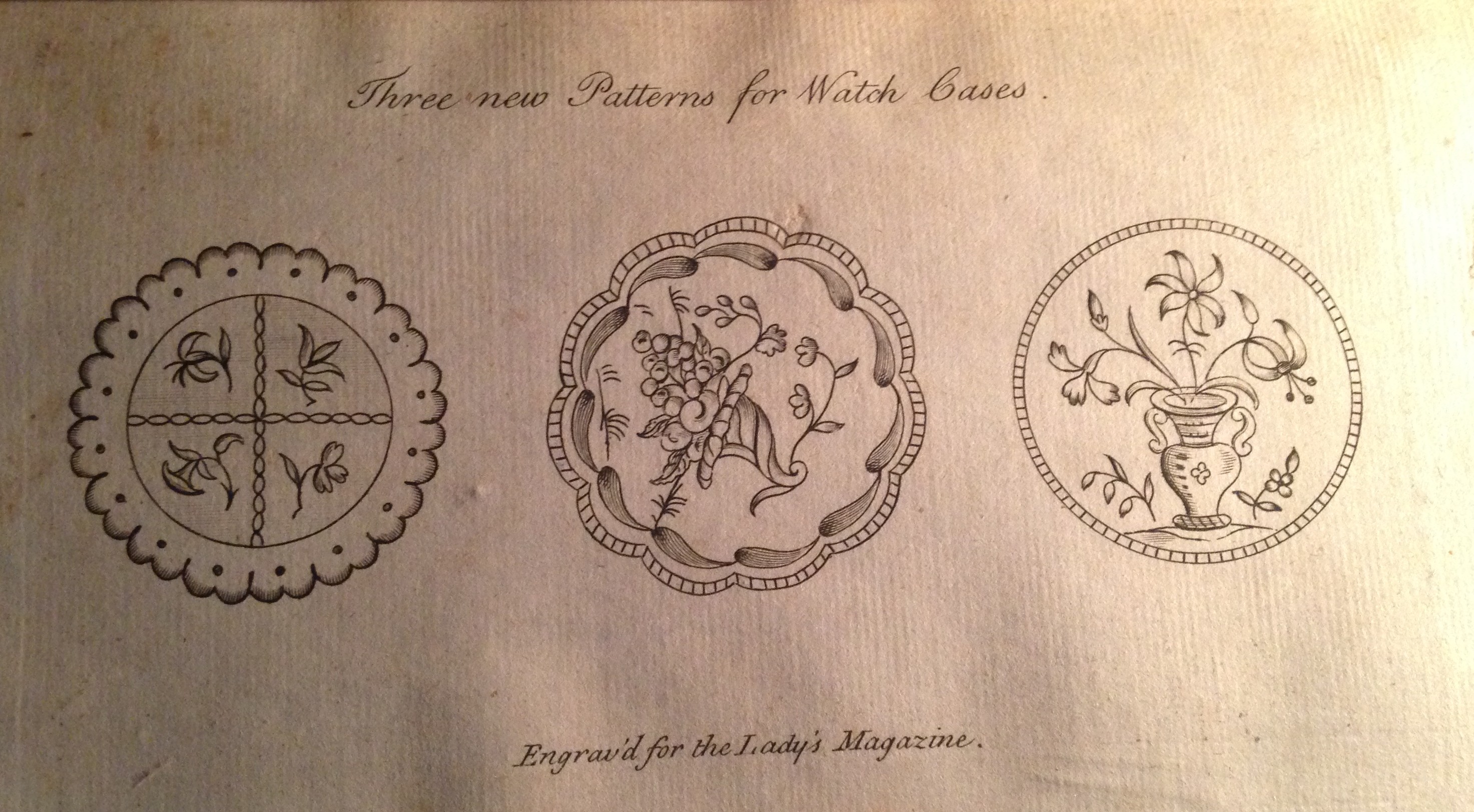

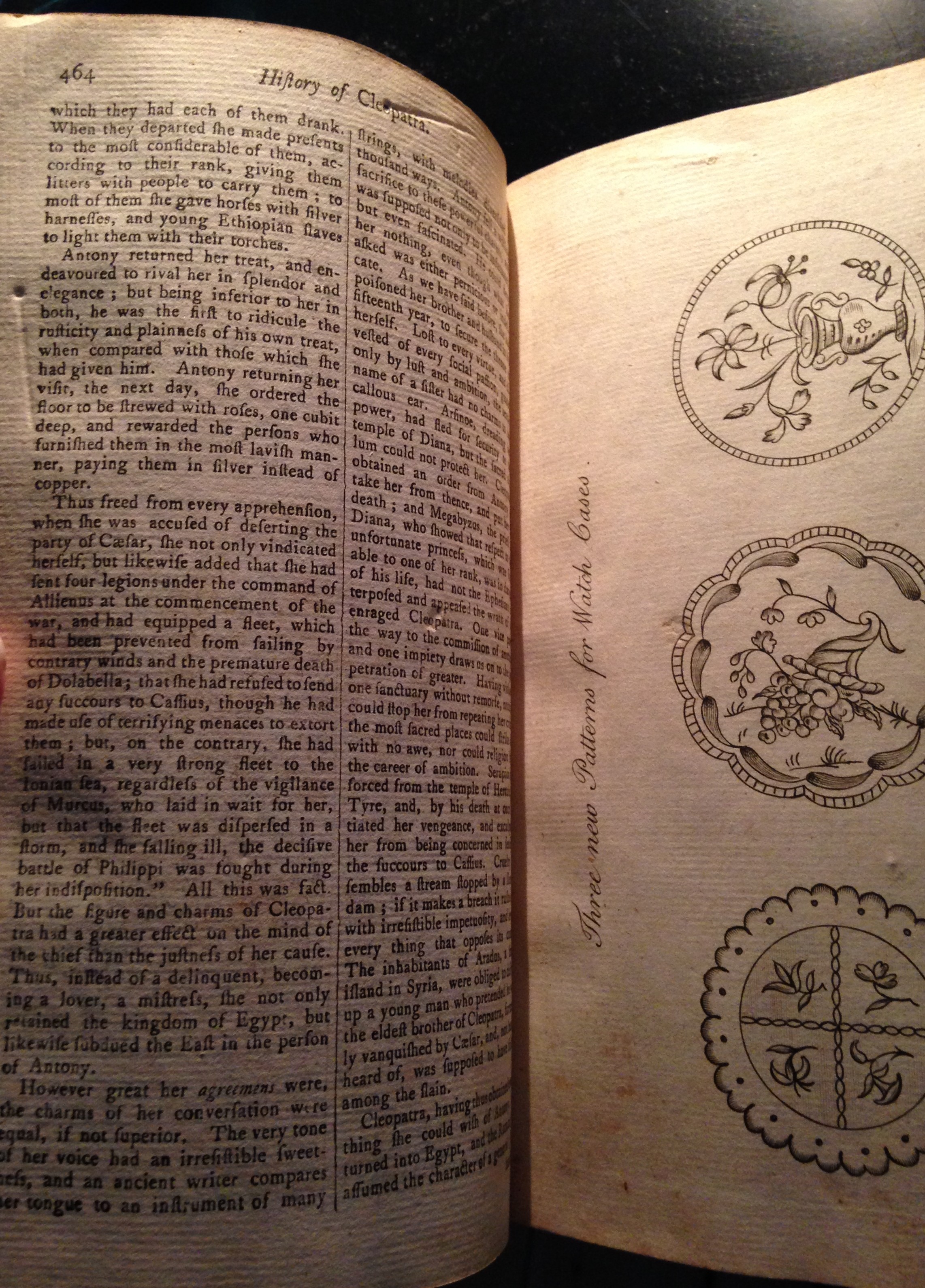

There is, of course, that connection to the past that seems so much stronger when handling the same worn and yellowed pages once thumbed through by the eighteenth-century reader. Certain that there was no pattern in the digital copy, the pdf was immediately consulted and it confirmed that the pattern in that edition of September 1775, according to the directions to the binder, been removed. As Jennie Batchelor pointed out in her blog last week, binders at times ignored or overlooked these directions, and by luck, the ‘three new patterns for watch cases’ had ben retained in my edition.

Certain that there was no pattern in the digital copy, the pdf was immediately consulted and it confirmed that the pattern in that edition of September 1775, according to the directions to the binder, been removed. As Jennie Batchelor pointed out in her blog last week, binders at times ignored or overlooked these directions, and by luck, the ‘three new patterns for watch cases’ had ben retained in my edition. In January 1779, G. Rffy’s writes that Bob Short’s column was printed opposite the sewing pattern which ‘rendered it rather more conspicuous than otherwise’ (LM X [Jan 1779]: 93). This is just as true today; periodicalists handling the material artifact now experience the same sense of surprise when turning the page in the middle of a discourse on religion to find a pattern for ruffles. Readers’ experiences of and engagement with the magazine’s various items could be altered by the location of text opposite an engraving or pattern. While the pattern for watch cases may seem relatively unimportant in the grand scheme of the Lady’s Magazine, it highlights the differences between working with digitized and material magazines, and also raises questions about the editorial practices regarding the positioning of text and engravings to, perhaps, render certain items ‘rather more conspicuous’.

In January 1779, G. Rffy’s writes that Bob Short’s column was printed opposite the sewing pattern which ‘rendered it rather more conspicuous than otherwise’ (LM X [Jan 1779]: 93). This is just as true today; periodicalists handling the material artifact now experience the same sense of surprise when turning the page in the middle of a discourse on religion to find a pattern for ruffles. Readers’ experiences of and engagement with the magazine’s various items could be altered by the location of text opposite an engraving or pattern. While the pattern for watch cases may seem relatively unimportant in the grand scheme of the Lady’s Magazine, it highlights the differences between working with digitized and material magazines, and also raises questions about the editorial practices regarding the positioning of text and engravings to, perhaps, render certain items ‘rather more conspicuous’.