One of the recurring themes in this blog has been our conviction that the much-slighted Lady’s Magazine occupied an important position in the literary field of its time. It offered some later successful authors with a first opportunity to get their work into print, as for instance ‘C.D.H.’ or Catharine Day Haynes who went on to publish novels with the popular Minerva Press, and, although a leading literary historian has dismissed its tales as ‘predominantly decorous, sentimental, and moral’,[1] Jane Austen may have disagreed. However, every single contributor to the magazine is worthwhile looking into, because even if they did not develop into famous authors in their own right or were the unknown toilers who paved the way for writers of more renown, through their minor literary, critical or philosophical interventions they all participated in the shaping of literary history.

It is easy to get carried away when investigating these contributors and to romanticize them as characters in the novel of their own lives, as some did themselves. A great many of the more obscure authors to the Lady’s Magazine were amateurs and few will have received payment for their submissions, so I used to wonder what it was that they got out of their efforts. I believe now that this is a cynical question for a cynical era, that would have been duly frowned upon in the age of Evelina. Part of the attraction of amateur authorship was the sheer thrill of it, the fashioning for oneself of a separate, often hidden second identity that made a change from one’s daily routine as a shopkeeper or unchallenged Georgian housewife. Eighteenth-century periodicals can themselves be a lot like eighteenth-century novels. Readers of the fiction of this period will know that there you are often given tantalizing dashes instead of (full) names for the leading characters, who sometimes go by mysterious spurious identities at that. Investigating a magazine you soon find yourself wanting to know all about the elusive flesh-and-blood people behind the countless paper-and-ink personae, represented by so many partial signatures and pseudonyms, with as much ardour as (though with less imagination than) Charlotte Lennox’s Arabella speculates about the ‘true’ identity of Edward the carp-stealing gardener. However, when the heroes are periodical contributors instead of characters in novels, the desired dénouement is not always possible.

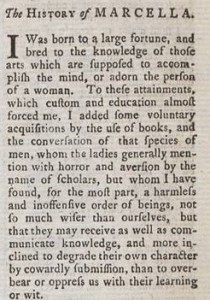

LM X (Jan 1779): p. 6. Image © Adam Matthew Digital / Birmingham Central Library. Not to be reproduced without permission.

This makes it all the more gratifying when we do find out what we wanted to know. Through our combined sleuthing we have learned a lot about quite a few contributors already, and we are adding these discoveries to our annotated index. Two weeks ago, Jenny reported on ‘R- ’, whom we now know for sure to have been Radagunda Roberts, a minor female author and translator from a family of intellectuals. Though now forgotten, she moved in prominent literary circles sufficiently to warrant her an entry in the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, where she is included as “R. Roberts”. This note was very helpful for the research leads it offered on Roberts, but the fact that its immensely knowledgeable and experienced author Arthur Sherbo could only trace the initial of her first name, while her nowhere near as active and (from a literary and cultural-historical point of view) less important male relatives left more paper trails, is symptomatic for the fate of many female writers. It feels good to finally be able to fill in the gaps.

That of course does not mean that the male members of the Roberts family would be irrelevant. Radagunda’s eldest brother Richard was the high-master of the prestigious St Paul’s School (London). She was also related to William Hayward Roberts, provost of Eton College, Anglican clergyman and religious poet, who may have been the “Rev. W. R.” who in 1785, about a year and a half after Radagunda disappears from the magazine, contributes a translated serialized extract from Juan Alvarez de Colmenar’s Annales d’Espagne et de Portugal (1741). This connection is as yet too tentative to dwell on, but will be pursued, as we are particularly interested in discovering relationships between authors outside of the magazine because this can help us to reveal networks for its many contributors. Reading and writing are social activities in this period to an extent that we are just beginning to understand.

Another relative, present at least once in the Lady’s Magazine, was Radagunda’s youngest brother, (another) William Roberts. Jennie has located a birth certificate indicating that he was born in 1725, and an inclusion in the A biographical dictionary of the living authors of Great Britain and Ireland of 1816 which suggests that he at least lived into his nineties (if he had lived many years beyond that he would arguably be more famous). He is on record as having served in the military before settling as a tutor in Wandsworth.[2] Though not a professional author, he does have two books to his name: the essay Thoughts upon Creation (1782) and a slim volume of Poetical attempts (1784), both issued by prominent London publisher Thomas Cadell.

The Thoughts are meant to prove that the state of the art in natural history and archaeology was in accordance with Scripture. It is for instance explained that ‘the eternal Essence, the invisible Jehovah’ inspired the invention of writing in the Middle East rather than elsewhere so that Moses could record the Torah,[3] and that, more recently, the findings on geography by the expedition of Captain Cook merely confirm the Book of Genesis.[4] While such views may seem odd several decades into the Enlightenment, they were by no means rare. However, the fact that Roberts went to the trouble of committing his Thoughts to paper may point towards a link to the then rising Evangelical movement. More hints about his ideological stances can be gleaned from the enthusiastic dedication of the Poetical attempts to Thomas Howard, 3rd Earl of Effingham, who in 1775 was the object of some controversy after his resignation from the British army in protest to the impending wars against the American colonial rebels. According to Roberts, Howard had hereby ‘manifested the true feelings of virtue, in rejecting emolument, when incompatible with principle’.[5] The Poetical attempts themselves are also intriguing, and for several reasons. Besides poetry by William Roberts himself, it also contains a poem ‘by Miss Roberts’, who could be one of William’s daughters Mary and Margaret (later literary executors to Hannah More), or indeed his sister Radagunda (unmarried and therefore also still a Miss). Either possibility would be exciting, but as the poem appears never to have been publicly acknowledged by or attributed to a specific author, we will probably never know.

Thomas Howard, by unknown artist

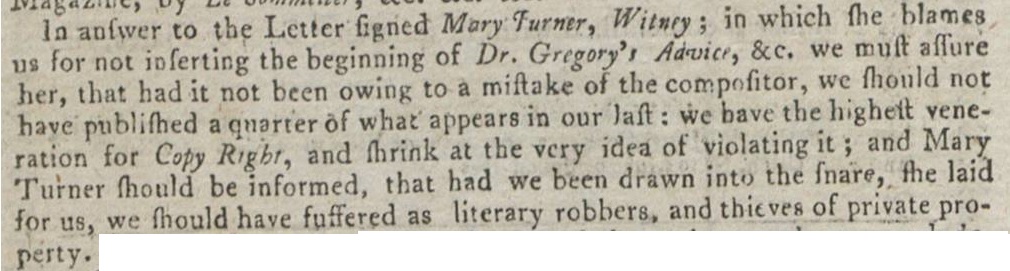

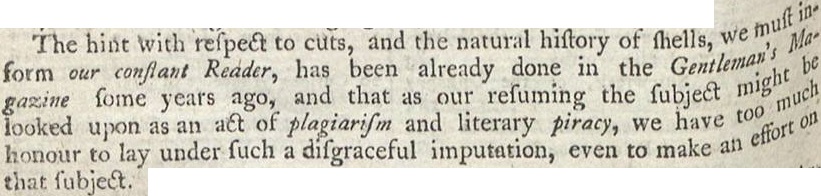

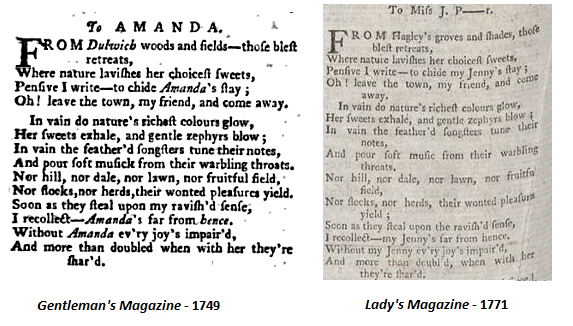

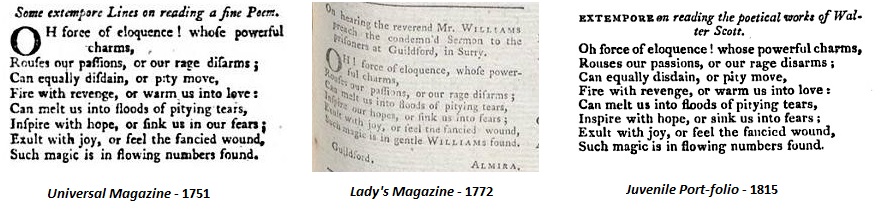

In a roundabout way, the attempts have at least helped with the attribution of a poem in the Lady’s Magazine. In June 1781 a poem entitled ‘Nancy. An Elegy’ appears in the magazine, with the signature ‘E. G’. After I checked this item against a few online databases I found that it was almost identical to an unsigned “Elegy” that appeared in the Gentleman’s Magazine in August 1758. There, however, the poem is addressed to a ‘Molly’ instead, making this one of many instances in the Lady’s Magazine of appropriated occasional verse for which only specific details were adapted in order to detach the purloined work from its original context. So, nothing unusual so far, but great was my surprise when I discovered that the poem, in the decades-old version of the Gentleman’s Magazine instead than in its more recent version of the Lady’s at that, was included three years later in a poetry collection by the brother of a regular contributor to our magazine. It seems unlikely that the fifty-nine-year-old William Roberts, who does not appear to have ever nourished strong ambitions to establish himself as a poet, would claim authorship for an unremarkable poem that he had not written himself. As he was 33 when it appeared in the Gentleman’s, he could certainly have been the original author. There is furthermore another poem addressed to ‘Molly’ among the attempts to corroborate this theory. Several scenarios can be imagined for how the adapted version ended up in the Lady’s Magazine 31 years after its original appearance. As said above, reader-contributors tacitly appropriated poems from other periodicals all the time, not rarely from sources as old as this. It is possible that Radagunda and her brother were as surprised as I was to see this poem suddenly resurface, submitted by whoever it was that chose to be known as ‘E. G.’. Alternatively, William could have been toying with the idea to collect his old poetic trials, and maybe wanted to test the waters by submitting pseudonymously an edited version of this elegy to the Lady’s Magazine, maybe motivated to change it slightly by the inconsistent attitude the magazine showed towards republication from rival periodicals such as the Gentleman’s.

Besides daughters, William Roberts also had a son, named (again?!) William Roberts. William junior is most likely the author of “Cephalus and Procris, A Tale, by a Youth of Fifteen”, also in the attempts. Years later he would write the first biography of Hannah More (1834), and, as editor of the Tory-Evangelical British Review (1812-1825), he has the unenviable claim to fame of being lampooned by Byron in Don Juan. We have not yet found any evidence that the third and final William or his sisters Mary and Margaret contributed to the Lady’s Magazine, but this may well turn out to be the case. Whatever we find out will be waiting for you along with our many other discoveries in the index!

Dr Koenraad Claes

School of English, University of Kent

[1] Mayo, Robert. The English Novel in the Magazines: 1740-1815. Evanston: Northwestern University Press, 1968. p. 188

[2] G. Le G. Norgate. ‘Roberts, William (1767–1849)’. Rev. Rebecca Mills. Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2004 [http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/article/23778] Last accessed 14 March 2016.

[3] Roberts, William. Thoughts upon Creation. London: T. Cadell, 1782. p. 23.

[4] idem, p. 59

[5] Roberts, William. Poetical attempts. London: 1784. n. p.