Cardiff Castle; LM VII (1776): 428. Image © Adam Matthew Digital / Birmingham Central Library. Not to be reproduced without permission.

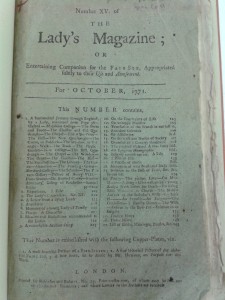

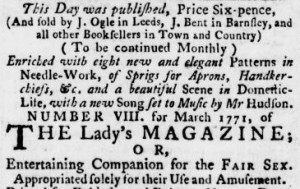

As Jenny told you in her post of last week, the three of us recently went to Cardiff to lead a workshop at the first annual conference of the Cardiff Romanticism and Eighteenth-Century Seminar (CRECS). I second Jenny’s enthusiasm about this initiative and want to join her in thanking our kind hosts for their hospitality. It was not only great to test out new ways to discuss our work with an audience that mostly had little prior knowledge of the Lady’s Magazine; while we were there, we also had the opportunity to check the holdings of the magazine in the Special Collections and Archives (SCOLAR) section of the Cardiff University library. Despite their similar names, Caerdydd and Caergaint (Canterbury) are quite far away from each other, and I had been eager to spend some time in this excellent research library since Jennie on an earlier visit discovered in the SCOLAR collections some copies of the magazine with the advertisements still in them. In a previous post on advertising I have already explained that these are very rare. Old periodicals tend to be handed down to us in annual bound volumes, and usually these have been purged of all items that the binders or librarians deemed too ephemeral for preservation. SCOLAR has no less than twenty-six annual volumes of the Lady’s Magazine proper in its collection, plus one volume each of the nefarious but terribly interesting piracies of the magazine issued by John Wheble and Alexander Hogg, which makes it one of the most extensive holdings of material relevant to our project anywhere. I was very pleased to find that two of the real-deal volumes in SCOLAR did come with a rich selection of adverts.

This may not seem much to be excited about, but it really is: the copies in the British Library, for instance, do not have a single advert in them. My previous post on advertising focused on the few adverts in the one monthly issue of the Lady’s Magazine – itself a rarity – that we have in our own (also splendid) Kent Special Collections, but at SCOLAR, there is a lot more. Their aforementioned annual volumes contain adverts originally published with the individual monthly issues, amounting to 20 different items for both. We cannot be sure that no adverts were taken out over the past two centuries, but we may have here the harvest for two whole years. What makes it even better, is that the adverts we have found at Kent are from 1771, and the Cardiff ones from 1804 and 1805. Although, admittedly, two volumes are not a great deal to go by, we can use this material as a basis for hypotheses about changing advertising policies in the Lady’s Magazine, and because of the central position of this publication in the market, in late-eighteenth / early-nineteenth-century British magazines in general. These adverts, as they always do, also reflect British social history. What is advertised in a magazine is what its readers are expected to want to buy, and which commodities agents in a capitalist society seek to acquire says a lot about what sociologists after Pierre Bourdieu call their ‘habitus’; a set of beliefs determined by what they (consciously or unconsciously) consider to be their place in society. There is not much circumstantial evidence to verify what the magazine itself indicates about its readership, so we are glad to be able to study adverts to find out what readers of the Lady’s Magazine were induced to buy, or rather: buy into. From this we can deduct information about who read the magazine.

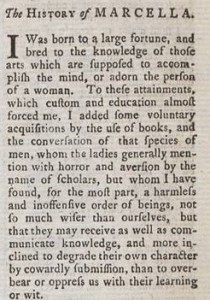

This newly-found material from the early nineteenth century corroborates our previous assumption, based on the magazine’s contents, that the magazine consistently spoke to a broad audience and took the middle class, and anybody who would aspired to be part of it, for its implied readership. The SCOLAR adverts all target consumers who have some money and leisure to spare for self-cultivation and for little indulgences, but do not attempt to sell luxurious goods or services that would be out of reach for the middling sort. Most of the advertisements, for instance, appeal to those who would improve their minds and their physical appearance.

The publisher B. Crossby advertised with a seven-page publication list, which includes books in all genres, refreshingly with no apparent proviso for the purported feminine perspective of the Lady’s Magazine as you sometimes find in female-gendered discourses at the time. Another publisher, Sharpe, advertised the ‘British Poets Series’ of affordable anthologies of canonical poets, and Cooke their series of ‘Cheap and Elegant Pocket Editions’; both again spanning a wide range of genres from belles lettres to popular science. Similarly, while Alexander MacDonald’s A Complete Dictionary of Practical Gardening (advertised by its publisher George Kearsley) may sound like a title on household management, it is in fact a popular-scientific work offering detailed information on botany, in the same way as the also advertised Topographical Description of Great Britain (Cooke again) provides knowledge with an application beyond the immediate domestic sphere. To accommodate the readership of the magazine amongst schoolchildren, or in this case perhaps rather their teachers and parents, publisher J. Harris offered the Original Juvenile Library with ‘New Publications for the Instruction of Young Minds in the Christmas Holidays’ (the poor dears). The Literary Miscellany flogged its reprints of literary and conduct literature though the magazine, and the General Review of British and Foreign Literature advertised too. Both were periodicals like the Lady’s Magazine, but operated in different genres and were therefore not direct competitors. Among the advertisements for literary publications, Elizabeth Inchbald’s twenty-five-volume edition of plays The British Theatre (1806-1809) publicized a work that will be familiar to readers of Jane Austen:

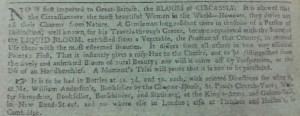

Readers were encouraged to improve their outward sophistication and physical wellbeing as well. The early nineteenth century may have been a particularly bad period for dental hygiene, as two cosmetics companies chose to advertise their dentifrices in the Lady’s Magazine. Readers had a choice between Larner and Company, who sold ‘[p]repared Charcoal, a most efficacious and and agreeable antiseptic for cleansing, whitening, and preserving the teeth’, and Messrs. Pressey and Barclay’s ‘India Betel-Nut Charcoal for preserving and beautifying the enamel of the teeth’. Larner also provided ‘Cheltenham Salts’, a mineral powder made out of evaporated spring water for those who could not go to Cheltenham Spa to take the waters there. Pressey and Barclay’s notice comes with a long endorsement signed ‘James Lynd, Late Head Hospital Surgeon On the Bengal Establishment’ that looks like an article in the magazine, making this a Regency-era precursor to what is known today as ‘native advertising’. Periscopic spectacles formed according to the natural curving of the eye were explained with illustrations and presented as the latest thing in optics by purveyors P. & J. Dollond, whose offices, so we read, were near St. Paul’s.

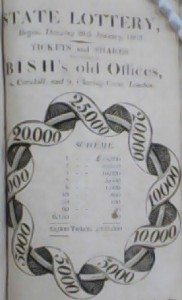

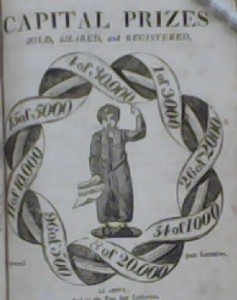

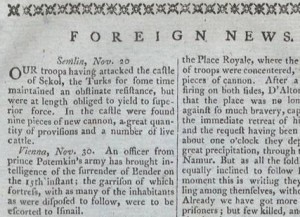

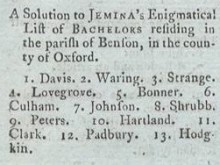

Nevertheless, the most conspicuous advertisements in these two volumes of the Lady’s Magazine are for lottery offices. State lotteries are fascinating phenomena that played a huge role in public in the long eighteenth century, and they too exploited the aspirations towards upward social mobility then prevalent throughout British society. Lotteries were organized in periods of great expenses such as wars or when public projects needed to be funded, from the late seventeenth century to their abolishment in 1826 after continuous debate about their moral repercussions, which are discussed at length in a recent book chapter by Prof. James Raven.[1] Then, lotteries were much more complicated than in the system of the National Lottery, in effect since their reintroduction in 1994. In the long eighteenth century, they were effectively a form of financial speculation. Tickets were tradable instruments at the stock exchange, and most of the government-licensed contractors that sold tickets were concerns of financial institutions and stock brokers. Tickets could go for dozens of pounds each and were therefore only affordable for wealthy individual consumers, and this is where the advertisement in the Lady’s Magazine come in. Lottery contractors employed ‘lottery offices’, such as that of Thomas Bish of the advert reproduced here, who next to whole tickets also sold ‘shares’; a cheaper subdivision of tickets that allowed the holder to a part of the winnings if the ticket in question turned out lucky. Not surprisingly, advertising lottery offices would mention earlier success rates to attract punters who were superstitious enough to believe that one office could be ‘luckier’ than another. This Mr. Richardson certainly chose his associates well:

Lottery offices were in direct competition with each other, and because they were not allowed to offer discounts or any other financial incentive, they needed to outdo their competitors with such clever advertising. Eye-catching illustrations abound, such as in this advert for the rivalling office of Branscomb and Co, also in the Lady’s Magazine. The design with the ticket wreath that we recognize from the Bish advert is here complemented with an enigmatic picture of a boy holding a piece of paper. Some research has revealed that this must be a so-called ‘bluecoat boy’. These pupils from Christ’s Hospital charity schools had a prominent role in the complex lottery drawing procedure, where their innocent hands drew the winning lots. They are regularly depicted in lottery adverts, often (though not here) in contorted poses demonstrating how the regulations required that they perform their part in this ritual: ‘he shall keep his left hand in his girdle behind him and his right hand open with his fingers extended’.[2] Branscomb’s perky urchin is in flagrant breach of the rules.

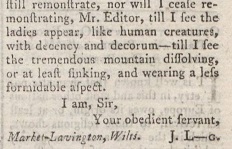

The fourth and final lottery advert in the Lady’s Magazine is my personal favourite. Not to be outdone by his former associate Branscombe’s cutesy bluecoat advert, and nearly a century before the music hall hit “The Man Who Broke The Bank At Monte Carlo”, the inventive Bish inserted a song sheet into his next advertisement. This is one of many ‘lottery songs’ that appear in broadsheets and adverts at the period. I shall leave you with the first stanza, which you will please to sing to the tune of ‘Mrs. Casey’ (however that may go):

Of all the schemes ingenious man

could ever boast the invention,

there’s none will reach to Bish’s plan,

they’re all too trite to mention.

So haste and buy, your fortune try,

And wealth secure for ever;

The lucky moment may slip by,

It’s surely Now or Never!

Dr Koenraad Claes

School of English, University of Kent

[1] Raven, James. “Debating the Lottery in Britain c. 1750–1830”. Random Riches: Gambling Past & Present. Ed. Manfred Zollinger. London: Routledge, 2016

[2] Qtd from unspecified source in: Grant, Geoffrey L. English State Lotteries 1694-1826: A history and collectors guide to the tickets and shares. London: privately printed, 2001. p. 21