As many of you know, the Lady’s Magazine project began as an effort to provide an annotated index of all of the text content of the Lady’s Magazine from 1770 to 1818. In addition to cataloguing every one of the around 15000 anecdotes, essays, serials and so on that the periodical printed during these years, we classified each of these items generically and provided keywords for every separate item in it to make its thousands of pages more easily navigable for modern readers and researchers.

Additionally, we worked to identify source texts for the magazine’s reprinted and excerpted material (no mean feat since periodical editors in this era were usually coy, shall we say, about such matters) and we also tried to identify as many as we could of the magazine’s anonymous and pseudonymous contributors.

We posted a number of our findings along the way on this blog, identifying the likes of the truly fascinating translator R. while also illuminating the careers of poets such as John Webb and fiction writers such as the Yeames sisters.

The indexing part of the project officially ended in 2016 with the end of our Leverhulme funded research project. But for me, this work is far from over. In recent months, I have given a paper on Radagunda Roberts and have written a journal article on Mary Pilkington and Catherine Day Haynes/Golland’s unacknowledged work for the Lady’s Magazine. I still haven’t given up on finding out more about gothic novelist Mrs Kendall either.

But I really wasn’t intending to think about attribution earlier this week when doing further research for a small section of the book on the magazine I am writing on the many, often beautiful, illustrations the periodical published in its more than six decade run. I was simply refreshing my memory about the key figures – G. M. Brighty, James Heath, Charles Heath, H. Mutley and Thomas Stothard etc. – with whom the magazine’s publishers collaborated and whose engravings, frontispieces and fashion plates ‘elegantly embellished’ successive issues of the Lady’s Magazine.

While doing this, I remembered a few occasions in the publication’s history where it didn’t have to commission engravings because contributors provided them with their copy. Once such case was in February 1784 when ‘P. T.’ submitted a description of a monument raised in Bath to honour the poet Thomas Chatterton. It didn’t take much ingenuity to work out that P. T. lightly conceals the identity of Philip Thicknesse, the travel writer and compellingly eccentric (some might say dubious or downright obnoxious) figure in the grounds of whose home the ‘Mausoleum’ was built and under which he would intriguingly bury his sixteen-year-old daughter Ann Frances in late 1785. But even if ingenuity (and Google) had failed me, the magazine’s ‘Correspondents’ column left me in no doubt about the identity ‘P. T.’ Indeed, the editor went out of his way to ‘acknowledge’ his ‘obligation to Capt. Thicknesse, for the honour of the Embellishment for this month’s collection’.

What I had forgotten about before I revisited this ‘Correspondents’ column (one of well over 600 the magazine printed) was the sentence that followed: ‘and we must likewise add, that his lady had previously favoured us with several singular marks of her patronage, and obligation; our Readers are obliged to her for one of the best pieces of Advice to her Daughter, that has appeared in any periodical work whatever; as well as several Lives from her Sketches of Learned Ladies in France.’

I suspect I originally read this late in the day, because the notes I had taken on it back in 2015 read: ‘CHECK: WAS ANN THICKNESSE REALLY AN ORIGINAL CONTRIBUTOR TO THE LADY’S MAGAZINE???’ (Yes: sometimes my research notes look like this initially, but I usually go back and answer any questions I pose myself and delete them.) In this case, I had clearly forgotten to follow up the lead! Fast forward three years…

Ann Thicknesse (née Ford, 1737–1824) has interested me for some time. A talented musician and writer, she was known primarily to me as the author of the three-volume biographical dictionary, Sketches of the Lives and Writings of the Ladies of France (1778-81), from which the magazine reprinted a number of extracts in the early 1780s, and upon which Matilda Betham and Mary Hays drew in their own biographical works a few decades later. [1] Thicknesse was much later the author of a now relatively obscure (and not desperately good ) novel entitled The School of Fashion (1800).

I didn’t know a great deal about Thicknesse’s life, beyond the fact that it was long and that she had had to rebuff in print the taint of scandal as a young woman when Lord Jersey, a considerably older and married admirer, tried and failed to make her his mistress. In 1762, Ann became Philip Thicknesse’s third wife, months after the death of his second wife (and Ann’s close friend), Elizabeth. They would have several children together (quite how many is disputed) and were married for thirty years until Philip’s death in France in 1792 on the last of their many European travels together.

Ann’s life and career are documented in various places including the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography and the indeispensible Orlando database of women writers in Britain. Both acknowledge that her writing career began in the 1760s with the publication of a staunch defence of her reputation in the face of Jersey’s allegations as well as two musical primers. A hiatus followed until the publication of Sketches in 1778, one that seems entirely natural given the amount of time Ann spent being pregnant, giving birth to and raising children in the next decade and a half.

But the note in the Lady’s Magazine’s ‘Correspondents’ column about the work entitled ‘Advice to her Daughter’ indicated clearly that this hiatus might not have been as long as we had suspected, and that Thicknesse’s literary career might have pre-dated the publication of Sketches. But what was the ‘Advice’?

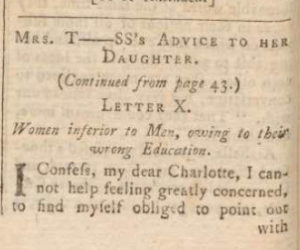

‘Mrs. T-ss’s Advice to her daughter’ was an original conduct-book serial published in thirteen parts in the Lady’s Magazine between 1775 and 1776. The opening installment of serial, which takes the form of letters on different themes, was accompanied by an editorial note stating that ‘these letters are the real sentiments of the lady who wrote them, and who meant to leave them in manuscript as a legacy to her daughters’, before she was persuaded to send them to the Lady’s Magazine’s publisher, George Robinson, by ‘a friend’ (6 [June 1775]: 294). The daughter addressed in the letters is named Charlotte, likely Ann and Philip’s daughter, Sophia Charlotte Thicknesse, born in June 1763. (The Thicknesse family name usually appears without the final ‘e’ in the historical record, just as Ann’s blanked out name also omitted the ‘e’ in the title of her series for the magazine.)

I’ve long been intrigued by ‘Mrs. T-ss’s Advice to her daughter’, not least because of its worldly but conservative views on three of my favourite preoccupations: dress, masquerades and dancing, all of which, Mrs. T. pointed out, had the potential to make women ‘disgustful’ in the eyes of others. But Thicknesse’s more reactionary views sat alongside her deep-seated conviction in the potential of the female mind.

Through-lines between her magazine conduct book and later Sketches become more apparent as the series unfolds and are plain to see in its penultimate installment from February 1776: ‘Women inferior to Men, owing to their wrong Education’. Of a mind with the magazine that published her manuscript, Thicknesse argued passionately here for female education. If women seemed ‘fantastical’ or ‘trifling’ then it was only because they were denied the same pedaogogical and life advantages that men had and not because of any innate frivolousness or intellectual inferiority. Women, she argued, were just ‘as capable of reason and deep reflection as men’ in a paragraph that lauded the examples of historian Catharine Macaulay and scholar Elizabeth Carter, to whom the first volume of Thicknesse’s Sketches would later be dedicated (89).

Through-lines between her magazine conduct book and later Sketches become more apparent as the series unfolds and are plain to see in its penultimate installment from February 1776: ‘Women inferior to Men, owing to their wrong Education’. Of a mind with the magazine that published her manuscript, Thicknesse argued passionately here for female education. If women seemed ‘fantastical’ or ‘trifling’ then it was only because they were denied the same pedaogogical and life advantages that men had and not because of any innate frivolousness or intellectual inferiority. Women, she argued, were just ‘as capable of reason and deep reflection as men’ in a paragraph that lauded the examples of historian Catharine Macaulay and scholar Elizabeth Carter, to whom the first volume of Thicknesse’s Sketches would later be dedicated (89).

‘Mrs. T-ss’s Advice to her daughter’ was not Thicknesse’s first published work but it was, arguably, her first recognizably literary work and now it has been identified as her work should be seen as an important precursor (literally and thematically) to her famous Sketches. Whether she wrote other original pieces for the Lady’s Magazine or other periodicals is not yet known.

As I wonder how many other notable women writers published works we have yet to discover in the Lady’s Magazine and rival periodicals I realize that while the book I am writing will get written some time in the not too distant future, the Lady’s Magazine project will always feel open-ended for me. There is still, I feel, so much to find out and so much I want to know.

Notes

[1] Sketches is in fact an an unacknowledged translation of Joseph La Porte’s Histoire littéraire des femmes françoises (1769). I am grateful to Gillian Dow for pointing me in the direction The Turbulent Seas of Cultural Sisterhood: French Connections in Mary Hays’s Female Biography’ (1803), Women’s Writing, 25:2 (2018): 167-85, for more information on this. (DOI: 10.1080/09699082.2017.1387337)

Prof Jennie Batchelor

School of English

University of Kent

Awesome write-up. I am a regular visitor of your site and appreciate you taking the time to maintain the excelent site.

Great!

Awesome

thanks for sharing it!

Νow I aam going to do my breakfast, afterward havіng my breakfast coming yet again to reaԀ more

news.

how can i see it?