Feral dogs photographed by A. Woodhouse http://africageographic.com/blog/feral-dogs-imfolozi/

The concept of secondary predator effects on degraded ecosystems is well established. If the large carnivores at the top of the ‘food chain’ are eliminated, then species lower down the pecking order are given a free reign to devastate prey species or the vegetation, if they are grazers (Borrvall and Ebenman, 2006; Duffy, 2002). By inference the presence of primary predators controls the trophic levels below them in the ecosystem.

Whilst large carnivores are necessarily rare, from a trophic, or food energy transfer, perspective (Colinvaux, 1990), they appear to have an amplified impact on the behaviour and presence of other species can be a significant moderating effect in ecosystems. A recent study identified that even perceived presence of large carnivores reduces the feeding routines and impact of secondary predators in particular in experiments with racoons (Suraci et al 2016).

Do these observations and phenomena relate in any way to the pressures on ecosystems in North Africa? Clearly, land use by mixed flocks of goats and sheep would be changed (to some extent) by the presence of large carnivores, although how this would affect long term landscape recovery is unclear (without some system to manage those flocks). There also is a suspicion that some Barbary macaque populations are be impacted by predation from feral dogs, particularly causing losses in infant monkeys.

Could lions provide an opportunity to deter overgrazing or the presence of feral dogs in those habitats of Barbary macaques?

Further Reading:

Borrvall, C. and Ebenman, B. (2006) Early onset of secondary extinctions in ecological communities following the loss of top predators. Ecology Letters, 9, 435–42

Butynski, T.M., Cortes, J., Waters, S., Fa, J., Hobbelink, M.E., van Lavieren, E., Belbachir, F., Cuzin, F., de Smet, K., Mouna, M., de Iongh, H., Menard, N. & Camperio-Ciani, A. (2008) Macaca sylvanus. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2008: e.T12561A3359140. http://dx.doi.org/10.2305/IUCN.UK.2008.RLTS.T12561A3359140.en. Downloaded on 26 February 2016.

Colinvaux, P. (1990) Why Big Fierce Animals Are Rare. Penguin Books.

Duffy, J.E. (2003) Biodiversity loss, trophic skew and ecosystem functioning. Ecology Letters, 6: 680–687 doi: 10.1046/j.1461-0248.2003.00494.x

Suraci, J.P., Clinchy M., Dill, L.M., Roberts, D. and Zanette L.Y (2016) Fear of large carnivores causes a trophic cascade. Nature Communications, 7, 10698 doi:10.1038/ncomms10698 http://www.nature.com/ncomms/2016/160223/ncomms10698/full/ncomms10698.html

Woodhouse, A. (2014) Feral dogs at iMfolozi. Africageographic, Posted: April 30, 2014 http://africageographic.com/blog/feral-dogs-imfolozi/

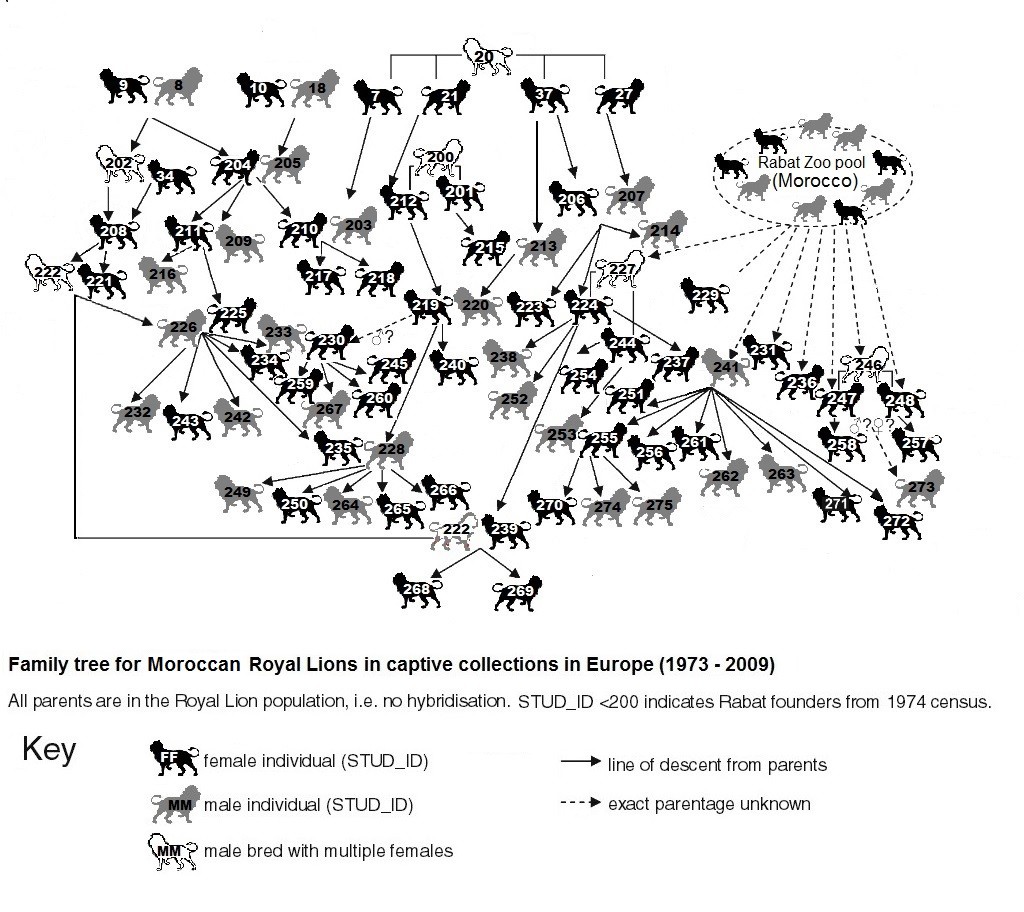

By the end of the 1990s efforts by several zoos to engage in a pan-European breeding programme for lions derived from the King of Morocco’s collection was beginning to fade. Only Port Lympne continued with an active breeding group, and a male from Rabat zoo (number 241 on the diagram opposite) was brought in to reinvigorate a pride which was developed from animals imported from Washington zoo in the 1980s. Up until that point they had reached a point of inbreeding within a family group.

By the end of the 1990s efforts by several zoos to engage in a pan-European breeding programme for lions derived from the King of Morocco’s collection was beginning to fade. Only Port Lympne continued with an active breeding group, and a male from Rabat zoo (number 241 on the diagram opposite) was brought in to reinvigorate a pride which was developed from animals imported from Washington zoo in the 1980s. Up until that point they had reached a point of inbreeding within a family group.

“…Between the Middle and High Atlas lies a rocky mountainous area where green oaks dominate the landscape…where the endangered Barbary leopard may still survive… Barbary macaques (Macaca sylvanus), Barbary sheep (Ammotragus lervia) and wild boars live there, and Cuvier’s gazelles (Gazella cuvieri) and Barbary red deer (Cervus elaphus barbarus) may also be reintroduced…lions may be released into a securely-fenced semi-natural enclosure…to live with minimum human intervention…, releasing them into an open area is out of question… “

“…Between the Middle and High Atlas lies a rocky mountainous area where green oaks dominate the landscape…where the endangered Barbary leopard may still survive… Barbary macaques (Macaca sylvanus), Barbary sheep (Ammotragus lervia) and wild boars live there, and Cuvier’s gazelles (Gazella cuvieri) and Barbary red deer (Cervus elaphus barbarus) may also be reintroduced…lions may be released into a securely-fenced semi-natural enclosure…to live with minimum human intervention…, releasing them into an open area is out of question… “