Leopards were commonly hunted in Morocco well into the 20th century.

A colleague recently visited the national park of Talassemtane in the Rif mountains touring the area with a local guide. The guide told them that these mountains, near Chefchaouen, still retained dense fir forests up until after the second World War and that only shepherds visited the summits because people who lived in the towns and villages of the valleys were afraid of the wild landscape and the possible presence of lions. According to the guide, researchers from the Ceuta, believed that the lion was still present during the 20th century up until the time when mountains of the area had been deforested. Do these observations have any basis in fact?

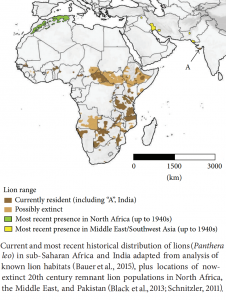

Certainly there were lions in Morocco up to and including the second world war, although they were seen further south. One was shot in the High Atlas Mountains as late as 1942 in the Tizi‐n‐Tichka pass, and a few years before a pair were seen south of the Atlas ranges on the Saharan fringes, with a further group seen in the same area in the mid 1930s. All of the known 20th century sightings were south of Fez, often in the areas around Ifrane, Azrou, Kenifra and further south around Toubkal or further south again beyond Assa.

The last known sighting in the north (the Rif Mountains and up towards Tetouan) was of a lion killed in 1895. However this does not rule out lions holding on in that region much later in small groups, especially if areas were not visited by people. For comparison, in Algeria several small lion populations were known up to the 1930s and up to the late 1940s, even though many sources suggest the disappeared by the 1890s. The last known sighting in Algeria was in 1956.

Extinction models show that, accounting for the frequency and spacing of sightings, lions could have persisted in both Morocco and Algeria up to the early 1960s (Black et al 2013; Lee et al, 2015). Only the destruction of habitat along the Mediterranean coast during the French-Algerian War suggests that lions might have disappeared earlier, perhaps by 1958.

Of course fear of lions (real or imagined) only tells part of the story of concerns by local people in the Rif Mountains in the 1940s. The other factor which may have concerned people in the area would be leopards. They still persist in Morocco today and would have been an important threat to livestock and, as we know from other regions, also a threat to people.

Further Reading:

Black SA, Fellous A, Yamaguchi N, Roberts DL. 2013. Examining the extinction of the Barbary lion and its implications for felid conservation. PLoS ONE 8(4):e60174

Guggisberg C.A.W. (1963) Simba: the life of the lion. London: Bailey Bros. and Swinfen

Lee TE, Black SA, Fellous A, Yamaguchi N, Angelici FM, Al Hikmani H, Reed JM, Elphick CS, Roberts DL. (2015) Assessing uncertainty in sighting records: an example of the Barbary lion.PeerJ 3:e1224 https://dx.doi.org/10.7717/peerj.1224

Schnitzler, A.E. (2011) Past and Present Distribution of the North African-Asian lion subgroup: a review. mammal Review, 41, 3.

he history of lion presence in countries across North Africa, and investigation into the final decline of the species in the region and the lessons which need to be learned for current lion declines in West and Central Africa are discussed.

he history of lion presence in countries across North Africa, and investigation into the final decline of the species in the region and the lessons which need to be learned for current lion declines in West and Central Africa are discussed.