Lions have enjoyed significant protection in Gujarat’s Gir Forest in India. There are accounts of colonial and local hunters shooting animals outside the state in the late 19th century.

Lions are in severe decline across sub-Saharan Africa, most particularly in West and Central African countries. Even in Eastern or Southeastern Africa many populations are now isolated by geography or fences. The decline of the species across Africa is worryingly similar to the historical disappearances of lions from other regions.

Recent collation and analysis of historical records have given insight into the range of the Barbary lion in North Africa, providing important insights into how lion populations are in decline, the point at which they are most vulnerable to extinction and what the animals tend to do under extreme persecution.

For example, Black et al. (2013) confirm that the range of lions reached far further south into the Saharan Atlas of Algeria than was ever known, even in the mid 1800s when numbers were higher and lion hunting was common in the region. Individual animals appear to have ranged across a wide expanse of arid habitat. This mean that the populations across Algeria could be considered contiguous with populations in the high atlas of southern Morocco.

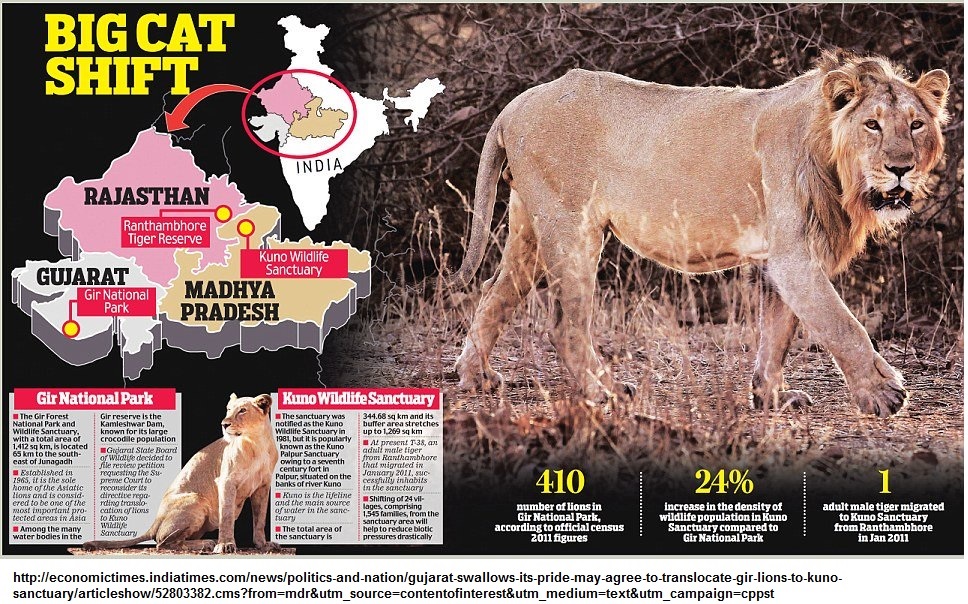

In India similar reports from 19th century colonial India include hunters taking lions in the Jahore and Marwar districts of Rajasthan in the 1870s, well north of their stronghold in the Gir forest, Gujarat state the last significant home of Asiatic lions over the past 100 years. In 1872 a professional hunter (Bhil Shikari) associated with a Mr. T. W. Miles brought in the skin of a full-grown Asiatic lioness which he had shot on the Anadra side of Mount Abu, the last met with in Sirohi districts. Around the same year a Colonel Hayland bagged four lions near Jaswantpura, in Marwar. These were apparently the last lions seen across the Kutch border into Rajasthan (Adams, 1899).

Lions are a long-lived species, so if isolated individuals range to less-threatened areas they are able to survive for prolonged periods, perhaps giving the impression of a population being maintained. This may not be a reality of persistence, but instead an indication of a single wandering, isolated individual as is suspected today in the recent lion sighting in Gabon.

From a conservation perspective, it is important to separate these exceptional ‘one-off’ sightings, from the true indicators of surviving micro-populations, the latter of which require careful systemic attention. For example, tiny populations of lions were thought to have survived in the remote Saharan Atlas mountains for decades after the species was considered extinct from North Africa (Guggisberg, 1963; Black, 2016). As for the exceptional one-off sightings – well they offer hope*; hope that a suitable habitat can be utilised for future lions population to find genuine refuge.

*Note: the recent unexpected sighting of a Spix Macaw in the wild, not seen in the area since the last known specimen disappeared in 2000 is a good example of an exception. No one believes the animal has been kept hidden for sixteen years – this individual it is most probably a recent captive release. However the learning point is – can this animal survive in the remaining habitat, does it display survival behaviours and would in situ conservation of the species be a viable proposition that can be taken forward seriously?

Reading:

Adams, A. (1899) The Western Rajputana States: A Medico-topographical and General Account of Marwar, Sirohi, Jaisalmir. https://books.google.com/books?pg=PA168&dq=%22marwar%22+lion+tiger&id=6ohCAAAAIAAJ&output=text

Black SA, Fellous A, Yamaguchi N, Roberts DL (2013) Examining the Extinction of the Barbary Lion and Its Implications for Felid Conservation. PLoS ONE 8(4): e60174.doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0060174

Black S.A. (2016) The Challenges of Exploring the Genetic Distinctiveness of the Barbary Lion and the Identification of Putative Descendants in Captivity, International Journal of Evolutionary Biology. vol. 2016, Article ID 6901892, 9 pages. doi:10.1155/2016/6901892

Guggisberg C.A.W. (1963) Simba: the life of the lion. London: Bailey Bros. and Swinfen

Saul H. (2016) Male lion filmed roaming in West African nation of Gabon for the first time in 20 years. The Independent http://www.independent.co.uk/news/world/africa/male-lion-filmed-roaming-in-west-african-nation-of-gabon-for-first-time-in-20-years-10152290.html

![Documented lion sightings since the middle ages across the Maghreb biome of the southern Mediterranean (light grey shading) north of the Sahara in North Africa (AD1500–1960). Open circles depict locations of general historical observations documented before 1800, adapted from [2]. Details can be sourced from [2, 8, 15]. Asterisks denote the locations of the various named major human population centres.](http://blogs.kent.ac.uk/barbarylion/files/2016/09/Fig-2-revised-medium-300x216.png)