If you reintroduce a large carnivore into a location adjacent to human population centres then human-wildlife conflict is likely. It also raises some important questison – what is ‘adjacent’ and what is ‘human wildlife conflict’.

The first bear to appear in Germany in over 170 years (a migrant who had left Italy, crossed Austria into Bavaria, was deemed to be behaving in a threatening manner by (purportedly) raiding bee-hives, killing 30 sheep, devouring pet rabbits and a guinea pig and raiding wastebins, as well as ‘rearing on his hind legs’ when approached too closely by some over-curious hikers. The latter incident doomed him to the decision by local authorities that he should be shot by a hunter – his body is now displayed as a taxidermy in a Munch museum.

Only this year a female bear with cubs was disturbed by a local cable-car worker as he searched for mushrooms and unsuprisingly she attacked him although left him with injuries without appearing to attempt to kill him. The outcome was an attempt by the authorities to capture her and remove her from the area (where she had been living peacefully in the wild for 13 years). The animal died during the capture.

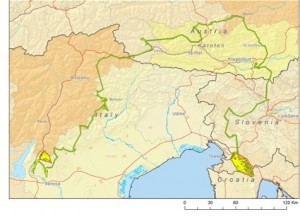

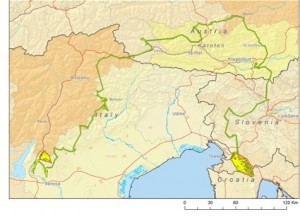

A wolf’s Journey: In zig-zagging his way from Slovenia to Italy, Slavc is estimated to have travelled some 2000 km. Photograph: Hubert Potočnik, University of Ljubljana

Experiences with reintroduced wolves has highlighted how far-ranging these animals become. Dispersion from release sites over thousands of kilometers is now being observed, although in these cases without apparent conflict issues despite proxmity to human habitation and infrastructure. Even the Netherlands hosted its first wolf in 150 years during 2013, just 30 miles from the densley populated North East coast, sparking alarmist headlines (although the animal that was found, was dead by a roadside).

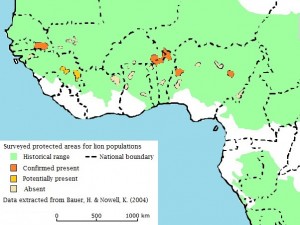

So, proximity to humans becomes inevitable. Natural behaviour (investigating bee-hives, attacking vulnerable livestock, defending cubs or warding off potential threats) becomes unacceptable aggression. What are the acceptable limits? What does this mean for lions?

Reading:

BBC (2008) Notorious bear ends up in museum. BBC News http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/world/europe/7314724.stm

Daily Mail (2013) The wolf’s at the door: first killer beast turns up in Holland for 150 years http://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-2361758/The-wolfs-door-Killer-beasts-roaming-Western-Europe-time-100-years.html

Davies E. (2014) Wild Bear Danzia dies after attempt to capture her faisl in Italy. The Guardian World News http://www.theguardian.com/world/2014/sep/11/daniza-wild-bear-dies-attempt-capture-italy

Nicholls, H. (2014) Incredible journey: one wolf’s migration across Europe. The Guardian Science http://www.theguardian.com/science/animal-magic/2014/aug/08/slavc-wolf-migration-europe?CMP=twt_gu

Whitlock, C. (2006) Feb up Germany kills its only wild bear. Washington Post. http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/content/article/2006/06/26/AR2006062600130.html