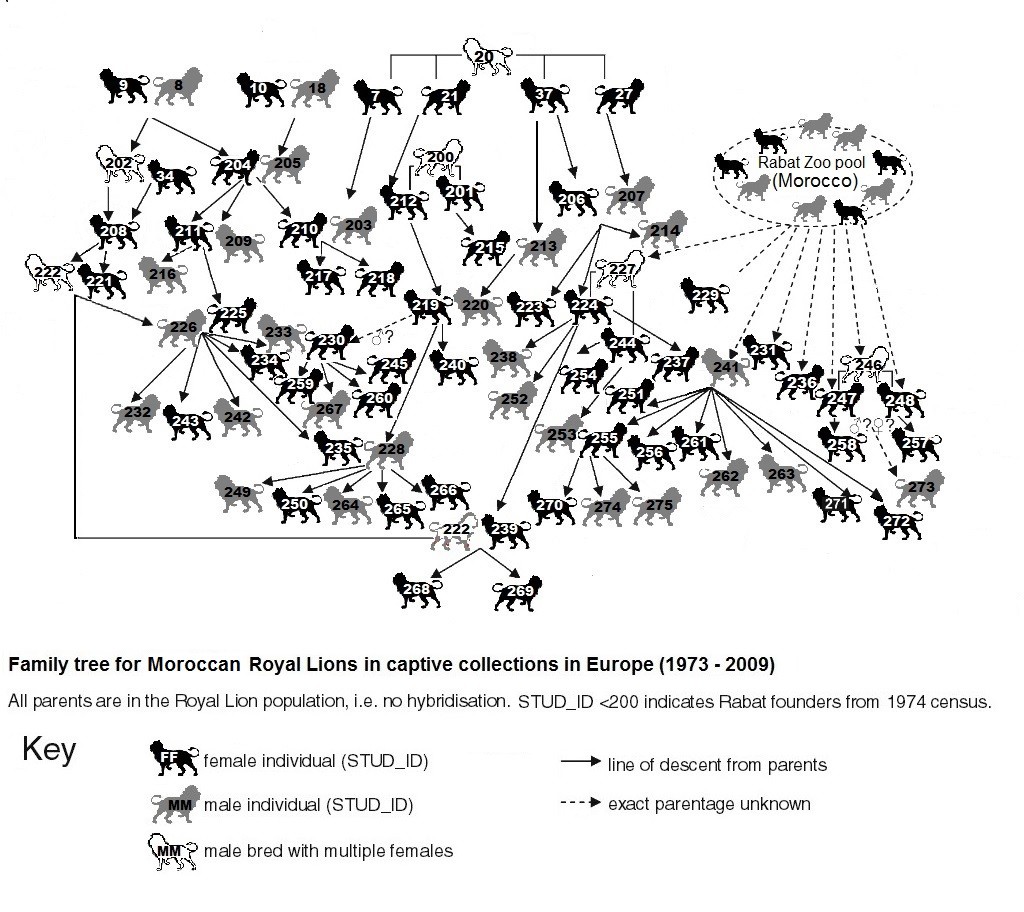

A recent paper on improving conservation decision making (Black, 2015) includes some of the data used in developing the Moroccan Royal Lion studbook (Black, Yamaguchi, Harland and Groombridge, 2010) as previously gathered by the author with Dr Nobuyuki Yamaguchi (University of Qatar) and Adrian Harland (Aspinall – Port Lympne Wild Animal Park).

Data on productivity (in this case, the number of cubs born) shows that since the initiative to revisit and re-catalogue the lions known to be direct descendents of the King of Morocco’s collection there has been a marked increase in the production of new cubs. The great news is that these are also form well-matched pairs with no further in-breeding.

However the analysis also shows that a greater level of breeding is still needed to bring the natural regeneration of the population under control. Currently there are practical restrictions to achieving this since clearly there are limits to the capacity that zoos have for increasing lion group sizes and for controlling breeding behaviour.

Further Reading:

Black S.A. (2015) System behaviour charts inform an understanding of biodiversity recovery. International Journal of Ecology http://dx.doi.org/10.1155/2015/787925

Black S, Yamaguchi N, Harland A, Groombridge J (2010). Maintaining the genetic health of putative Barbary lions in captivity: an analysis of Moroccan Royal Lions. Eur J Wildl Res 56: 21–31. doi: 10.1007/s10344-009-0280-5

Yamaguchi N, Haddane B. (2002). The North African Barbary lion and the Atlas Lion Project. International Zoo News 49: 465-481.

By the end of the 1990s efforts by several zoos to engage in a pan-European breeding programme for lions derived from the King of Morocco’s collection was beginning to fade. Only Port Lympne continued with an active breeding group, and a male from Rabat zoo (number 241 on the diagram opposite) was brought in to reinvigorate a pride which was developed from animals imported from Washington zoo in the 1980s. Up until that point they had reached a point of inbreeding within a family group.

By the end of the 1990s efforts by several zoos to engage in a pan-European breeding programme for lions derived from the King of Morocco’s collection was beginning to fade. Only Port Lympne continued with an active breeding group, and a male from Rabat zoo (number 241 on the diagram opposite) was brought in to reinvigorate a pride which was developed from animals imported from Washington zoo in the 1980s. Up until that point they had reached a point of inbreeding within a family group.