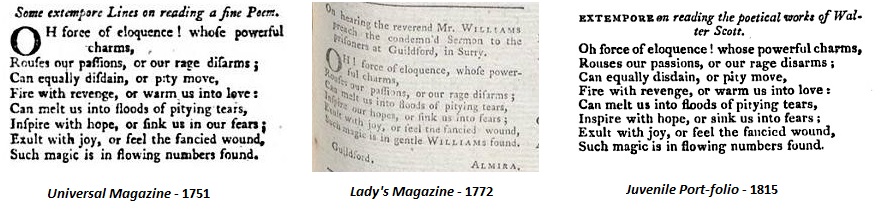

In the past few weeks, a recurrent topic in our blogs has been the regular appearance in the Lady’s Magazine of material taken from other sources, as opposed to original submissions. Our interest in this matter was sparked by a new phase in our work on the annotated index. I have recently started cross-checking the over 14,000 items in the magazine with several online databases, as manual a job as they come in the age of digital research, and noticed that a considerable number of items appearing without ascription in fact had appeared elsewhere first. There are a number of possible reasons why the magazine does not always own up about this: the editors were sometimes fooled themselves by reader-contributors (as I argued in my last), they felt that they were legally and ethically entitled to republish without acknowledgement, or they thought that acknowledging republications might tarnish their reputation for offering novelty. Printing non-original material without ascription was of course a widespread practice in the eighteenth-century press, and several readers of our blog have kindly contacted us to tell us about their own thoughts and experiences.

One highly important problem that repeatedly surfaced was one that usually takes some explaining to people who do not dwell – day in, day out – in the fascinating / exasperating world of periodical history: what to call this ubiquitous phenomenon. Last week, Jennie argued persuasively against using ‘the P-word’, plagiarism, for unacknowledged republications in eighteenth-century magazines, even if we would not hesitate to use it for such items as they occur in publications of today. She pointed out the notoriously hazy copyright laws of the period, and the equally relevant difference between eighteenth-century ethical notions of intellectual property and our own. We were excited and very grateful that Prof. David Mazella, who has done vital work on the Lady’s Magazine before, accepted Jennie’s invitation to write a response.

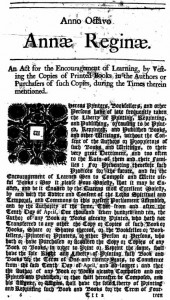

Prof. Mazella there elaborates on the issue of ambiguous authorship, and adds (amongst other pertinent suggestions) that a prominent cause of this ambiguity was that periodicals were in the eighteenth century not explicitly covered by copyright legislation. As he points out, copyright was at the time regulated under the Statute of Anne (1710). This pivotal legislation ended the monopoly of the Stationers’ Company by for the first time stipulating that copyright was not to be held in perpetuity, but for a fixed period. From now on, copyright was also subject  to other specific regulations, that were intended to protect not only the interests of the author, but also those of society at large, by creating what we now call the ‘public domain’ so that texts that were out of copyright could circulate freely.[1] Even though publishers kept referring to obsolete legislation to claim an unlawful absolute property of works that they originally issued, the judges usually would have none of this, and the Statute worked relatively well for books. However, Prof. Mazella, following Slauter,[2] suggests that the anarchic attribution policy of magazines was made possible by a lack of specific regulations in the Statute concerning periodical publications, and an unwillingness of the publishers’ sector to remedy this because the industry had come to rely on the manipulation of such unclear legal descriptions. This enabled, for example, a proliferation of newspapers, as snippets of texts regarded as ‘news’ could in slightly altered phrasings quickly travel across different titles, to the point that it is nigh on impossible to find out in which publication they originate. Prof. Mazella suggests ‘that the brief “textual units” of the [Lady’s Magazine], though formally and generically examples of short fiction, moral essays, biographies, etc., were […] treated on the model of the newspapers’ “textual units,” as a kind of readily accessible, transformable information that could be extracted or reworked as needed’. Using the term ‘plagiarism’ for this would be misleading, as we tend to use this term to denote, with an eighteenth-century definition also quoted by Slauter, ‘surreptitious theft of a named property’.

to other specific regulations, that were intended to protect not only the interests of the author, but also those of society at large, by creating what we now call the ‘public domain’ so that texts that were out of copyright could circulate freely.[1] Even though publishers kept referring to obsolete legislation to claim an unlawful absolute property of works that they originally issued, the judges usually would have none of this, and the Statute worked relatively well for books. However, Prof. Mazella, following Slauter,[2] suggests that the anarchic attribution policy of magazines was made possible by a lack of specific regulations in the Statute concerning periodical publications, and an unwillingness of the publishers’ sector to remedy this because the industry had come to rely on the manipulation of such unclear legal descriptions. This enabled, for example, a proliferation of newspapers, as snippets of texts regarded as ‘news’ could in slightly altered phrasings quickly travel across different titles, to the point that it is nigh on impossible to find out in which publication they originate. Prof. Mazella suggests ‘that the brief “textual units” of the [Lady’s Magazine], though formally and generically examples of short fiction, moral essays, biographies, etc., were […] treated on the model of the newspapers’ “textual units,” as a kind of readily accessible, transformable information that could be extracted or reworked as needed’. Using the term ‘plagiarism’ for this would be misleading, as we tend to use this term to denote, with an eighteenth-century definition also quoted by Slauter, ‘surreptitious theft of a named property’.

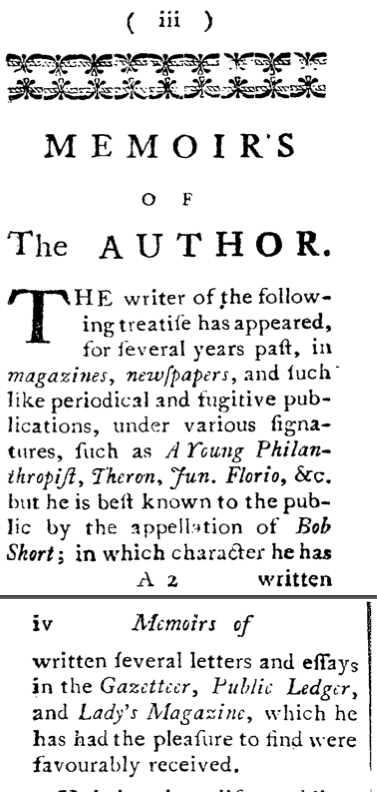

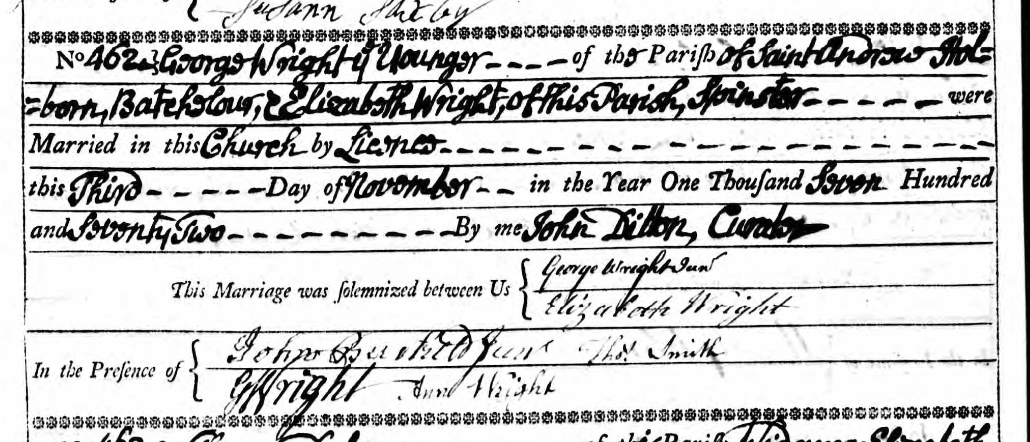

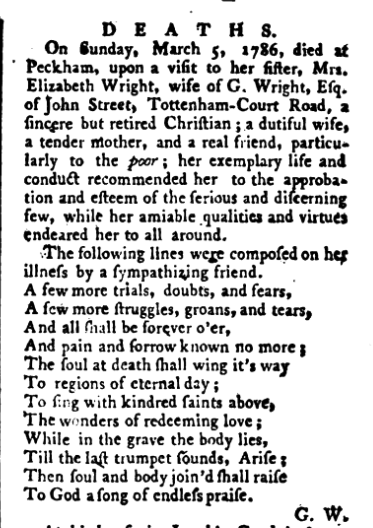

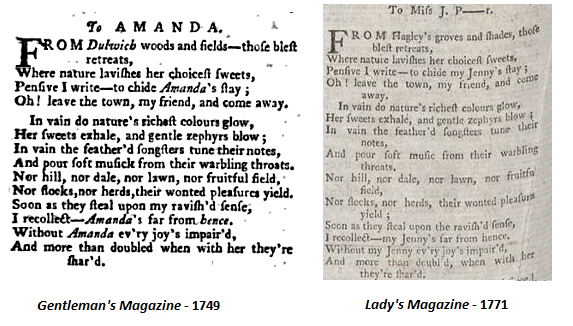

I fully agree that the connotations of the P-word are misleading. Furthermore, an allegation of plagiarism requires an assessment of the intentions of the alleged plagiarists, which is obviously highly precarious when you are dealing with authors about whom you have little or no information. Although I have in a past blog post once referred to certain items as ‘plagiarized’, I have reserved this verdict precisely for those cases where the ‘surreptitious’ appropriation of another’s labour seemed clear to me. For instance, when a reader-contributor, without acknowledgement, cheekily adopts the entire text of a poem, except for all references to people and places proper to the original poet, swapping these for cherished connections of her/his own. The reasons why I restricted it to this sense is that I agree with the points made by Jennie and Prof. Mazella, and their recent posts have convinced me that I should drop the term altogether. In what follows, I would nevertheless like to address (briefly) the abovementioned two ideas that are frequently cited in discussions of the supposed absence of a notion of fixed authorship during the eighteenth century: (1) the legal argument that there is no specific legislation for copyright of magazines in the period, and (2), the ethical argument that people did not think of the ownership of intellectual productions as we do today. Both are correct; they however do require, in my opinion, some nuance.

It is of course true that the Statute of Anne does not explicitly refer to publications other than books. Because of this, the republication of content between periodicals was always safe, as lucidly explained by Prof. Mazella. That, however, does not mean that there was no legal praxis concerning periodicals appropriating content from books, and in many cases this quite simply derives from the more straightforward regulations on the book trade. This is an important consideration because a significant number of republications in the magazines were taken not from other periodicals, but from books. Eighteenth-century copyright boils down to the general rule that, while texts are in copyright, republication in any form is prohibited to anyone but the copyright holder. This includes serialization in periodicals. However, partial republication, for instance the extracting of books in periodicals, was not covered by this. Even abridgements were sometimes ruled to be new works, thereby not constituting infringements of copyright, when the efforts of the editor/author would have produced a text that had the added value of brevity to a hurried reader, although here, problematically, intentions and motives needed to be gauged. This is also how magazines defended their miscellaneous character: the ongoing boom in publications had made it impossible for readers to keep up with everything that was being printed, so the magazines offer a digest tailored to their needs.

In his invaluable history of copyright in Britain, Ronan Deazley cites two cases against pioneering magazine publisher Edward Cave of the Gentleman’s Magazine (1731-1922).[3] These may offer a simpler explanation for the prevalence of extracts in magazines than the parallel to news items circulating across newspapers. In Austen v. Cave (1739) the plaintiff was publisher Austen, who held the copyright to the moral treatise The Nature, Folly, Sin and Danger of Being Righteous Over-Much (1739) by Joseph Trapp. The defendant, Cave, had excerpted this work, and was now accused of infringing the plaintiff’s copyright. Cave defended himself by stating that he excerpted books all the time, and that this was usually welcomed by the publishers and authors. He also referred directly to the Statute of Anne by stating that he only had intended to republish a part, and not the whole, and that too stringently applying the regulations as to copyright would be detrimental to the dissemination of knowledge that would have been the Statute’s main objective. Still, an injunction against further publication was obtained by the plaintiff, only to be lifted if Cave could satisfactorily prove that it had never been his intention to republish the work in its entirety. Cave failed to convince the judge, and therefore was forbidden from resuming the series of extracts. The second case, Cogan v. Cave (1743), is similar. The Gentleman’s Magazine excerpts Eliza Haywood’s Memoirs of an Unfortunate Young Nobleman (1743), copyright holder Thomas Cogan obtains an injunction, but this is lifted after Cave has cleared himself. Deazley suspects that Cave had once again referred to the Statute.

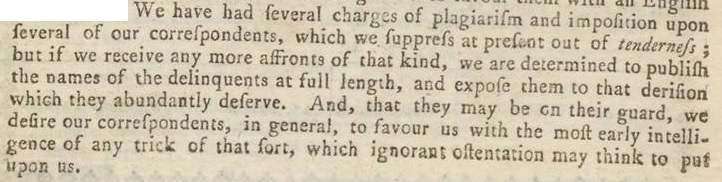

Both items could just as well have appeared in the Lady’s Magazine, where extracts from moral treatises and novels abound too. Only rarely do editorial notices betray any misgivings about such republications when these appear unsigned (presumably furnished by staff writers), but the editors do get nervous when they catch reader-contributors at sending in unascribed items for publication in the magazine. Here is one example from 1776:

LM VII (March 1776): facing p. 116. Image © Adam Matthew Digital / Birmingham Central Library. Not to be reproduced without permission.

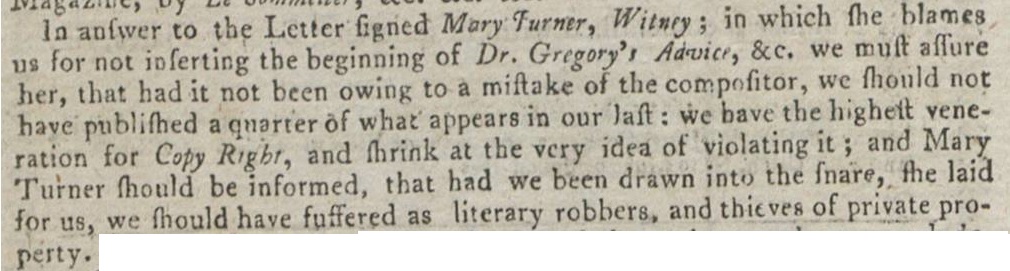

I have in a previous post referred to this sort of moral posturing as a sign of hypocrisy, but after further consideration, I think it rather was a strategy of risk containment. Although they had no actual qualms about repurposing content, the editors may have wanted to discourage readers from submitting non-original items without acknowledgement, because they had no control over these. Caution was advised, because republication could land you in court and make you squander time, money and your reputation, as every rival magazine would gleefully report on court proceedings against you. Whether or not to acknowledge the source for a republished item must have been regarded as a call to be made by the editors, not the readers. If there was no deontological argument against unacknowledged republication, this would arguably not have been a concern at all. Consider also the following notice, appearing after the magazine had published an extract from Dr. Gregory’s conduct book A Father’s Legacy to his Daughters (1774):

LM XV (Aug 1784): facing p. 36. Image © Adam Matthew Digital / Birmingham Central Library. Not to be reproduced without permission.

“Mary Turner” was most likely a reader-contributor who submitted the item in question without due ascription to the original source. Even though this was only an excerpt of about a page, and the magazine should legally have had nothing to worry about, there appears to have been some worry about the mere allegation of content piracy.

It may be relevant to remark that plagiarism, despite what is commonly thought, is actually not a legal concept, but rather pertains to the ethics of authorship. After all, even today you can plagiarize a text that is in the public domain without having to worry about any legal consequences, because you did not infringe any copyright. This brings me to the second assumption concerning ambiguous authorship in the eighteenth century, being the argument about publishing ethics. There are countless accounts of publishers and authors resenting the appropriation of their labours, but I believe that it is also easy to overstate the claim that readers would not have cared about correct attribution. The abovementioned attempts of the editors to deny that the Lady’s Magazine featured unacknowledged republications, despite these being undeniably present, and the magazine’s staff writers’ cosmetic edits to decontextualize appropriated material suggest that the reputation of offering (mainly) original matter, and reliably acknowledging non-original items, was deemed a valuable asset. A certain part of the readership, large enough to fuss about, must have cared.

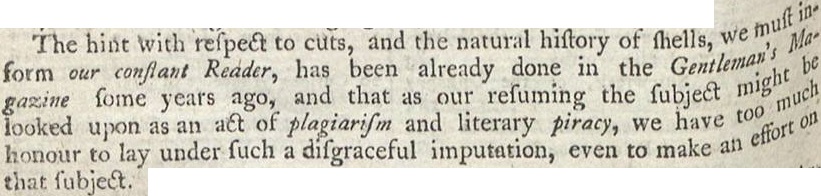

As Slauter indicates, the term ‘plagiarism’, in exactly the sense that we use it today, already occurs in the 1730s.[4] Although I have not yet had time to check all possible associated search terms exhaustively, I did find that there were at least eighteen instances of the term ‘plagiarism’ in the Lady’s Magazine between 1770 and 1800, and three of ‘plagiarist’ . These sometimes occur in discussions (often heated) between reader-contributors about the originality of submitted pieces. To do the subtleties of this debate justice, we will return to the attitudes of readers towards the P-word in a future post, but one more example from an editorial notice may suffice to prove that there definitely was an ethical dimension to republication that went beyond legality.

LM XI (June 1780): facing p. 284. Image © Adam Matthew Digital / Birmingham Central Library. Not to be reproduced without permission.

This even though, as I have found, the magazine’s staff writers had repeatedly repurposed items from the Gentleman’s Magazine before, without acknowledgement. It’s all very complicated!

Dr. Koenraad Claes

School of English, University of Kent

[1] Cf. Mark Rose, “The Public Sphere and the Emergence of Copyright: Areopagitica, the Stationers’ Company”. Privilege and Property: Essays on the History of Copyright, Ed. by Ronan Deazley, Martin Kretschmer and Lionel Bently, Cambridge: Open Book Publishers, 2010. <http://books.openedition.org/obp/1066> [last accessed 23 Sep. 15]

[2] Will Slauter, “Upright Piracy: Understanding the Lack of Copyright for Journalism in Eighteenth-Century Britain”, Book History, 16.1 (2013), 34-61.

[3] Ronan Deazley, The Origin of the Right to Copy, Oxford: Hart, 2004. pp. 79-80

[4] Slauter 2013, p. 48