Frances has very kindly provided the following summary of our discussion on The Stepford Wives:

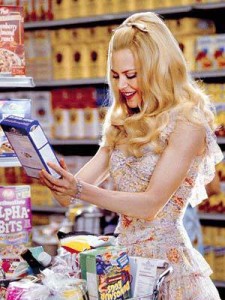

During our discussion  on The Stepford Wives it was noted how different the 1975 version is to its 2004 remake, particularly in regards to the latter’s ‘happy ending’. It was remarked that this remake completely removes the social commentary of the original which, whilst depressing, is absolutely necessary and crucial to understanding the film’s political contexts and its relevance to the Gothic. Indeed, it was noted that Forbes’s The Stepford Wives continues to be a powerful film precisely because many of issues it raises – especially in respect to society’s views on women – are unfortunately still relevant today and visible in contemporary culture.

on The Stepford Wives it was noted how different the 1975 version is to its 2004 remake, particularly in regards to the latter’s ‘happy ending’. It was remarked that this remake completely removes the social commentary of the original which, whilst depressing, is absolutely necessary and crucial to understanding the film’s political contexts and its relevance to the Gothic. Indeed, it was noted that Forbes’s The Stepford Wives continues to be a powerful film precisely because many of issues it raises – especially in respect to society’s views on women – are unfortunately still relevant today and visible in contemporary culture.

We also discussed Joanna as a Gothic heroine and, despite her resourcefulness and defiance against the forces of the Men’s Association early on in the film, it is strange that she does not attempt to fight against Diz and his murderous plans during the film’s climatic, penultimate scene. This may have been, in part, because Joanna runs through the old, dark house unarmed (having lost the fire poker to Diz at the beginning of the sequence), which led to the observation that Joanna – rather unusually – explores this space empty-handed. A common trait we have observed in other Gothic films is how the heroine usually explores the dark and (potentially) dangerous space of the Gothic house with a light source, such as the candelabra in The Innocents (1961) or torch in Secret Beyond the Door (1947). Such scenes are emblematic of the Gothic heroine’s exploratory nature, and the extreme use of light and shadow of these moments speak to the larger thematic concerns of the narrative which usually involves the exposing of previously hidden or repressed secrets.

We also discussed Joanna as a Gothic heroine and, despite her resourcefulness and defiance against the forces of the Men’s Association early on in the film, it is strange that she does not attempt to fight against Diz and his murderous plans during the film’s climatic, penultimate scene. This may have been, in part, because Joanna runs through the old, dark house unarmed (having lost the fire poker to Diz at the beginning of the sequence), which led to the observation that Joanna – rather unusually – explores this space empty-handed. A common trait we have observed in other Gothic films is how the heroine usually explores the dark and (potentially) dangerous space of the Gothic house with a light source, such as the candelabra in The Innocents (1961) or torch in Secret Beyond the Door (1947). Such scenes are emblematic of the Gothic heroine’s exploratory nature, and the extreme use of light and shadow of these moments speak to the larger thematic concerns of the narrative which usually involves the exposing of previously hidden or repressed secrets.

Joanna’s interaction with the house is markedly different in this respect and it was suggested that Diz’s presence in the scene could be the disruptive factor: the Gothic heroine usually explores the domestic space alone or, at the very least, the threat of a male is normally provided by the story’s husband or love interest. The Stepford Wives is different on both these counts and this could represent another way the film adapts and modifies the traditions of the Gothic in order to speak to the film’s wider political contexts and concerns. In this reading Diz is not just a substitute for the heroine’s suspicious spouse but rather an embodiment of patriarchy itself. This is reinforced by Diz’s lead role in the Men’s Association which is the dominant organisation controlling the town and ensuring male privilege and advantage. In this way, it is entirely apt that Joanna’s interaction with the house – which ultimately leads to her demise – is depicted in this way. If The Stepford Wives functions allegorically as a comment upon the destructive nature of patriarchal control, then any attempt on Joanna’s behalf to resist Diz’s manipulation is therefore futile: the house, like Stepford and society more broadly, are already shaped and controlled by Diz and what he stands for. This socio-political reading is reinforced again by Joanna’s traumatic discovery of her double at the end of the sequence. The sight of Joanna’s submissive doppelganger as she sits within a mock bedroom functions as another personification of women’s domestic and sexual enslavement.

reading is reinforced again by Joanna’s traumatic discovery of her double at the end of the sequence. The sight of Joanna’s submissive doppelganger as she sits within a mock bedroom functions as another personification of women’s domestic and sexual enslavement.

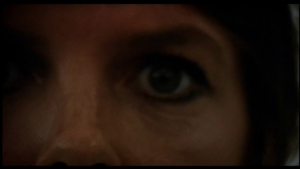

Interestingly, the film explores these themes of oppression and objectification on an aesthetic level too. Joanna’s job as a photographer complements her role as the inquisitive Gothic heroine although the agency Joanna enjoys through her control of the lens (along with her investigative abilities) is always compromised. Significantly, Joanna is not a successful photographer and the only pictures which garner critical interest are of domestic, family scenes. Instead The Stepford Wives emphasises how Joanna fails to look both in her capacity as a photographer, and metaphorically in her ability to see the truth about Stepford’s community. The point-of-view shots used to depict Joanna’s picture taking become ironic: Joanna’s control over these images (and, by extension, over what the viewer sees) is illusionary and transitory, and Joanna herself will quite literally be replaced by a body that has been made to fulfil an image which adheres to the standards set by the men’s desires. The moment Joanna discovers her automaton replacement reflects this usurpation of Joanna’s agency and her ability to look. When Joanna first enters the mock bedroom, her gaze is represented by a point-of-view shot which pans from left to right, scanning the room. Notably, this is the last time we see events strictly from Joanna’s perspective. Joanna’s discovery of the robot is depicted first through a close-up on Joanna’s face for a reaction shot, and then another pan (with accompanying aural cues) reveal the source of her horrified response. Joanna loses agency of the image at the moment when she comprehends Stepford’s sinister secret and will ultimately lose her life. Indeed, subsequent edits in the shot-reverse shots between Joanna and the android emphasise this connection between the film’s larger themes and its stylistic choices further: an edit frames a close-up on the double’s synthetic breasts, visible beneath the see-through negligee it wears. The camera’s voyeurism aptly reflects the triumph of the Men’s Association in objectifying the women of Stepford and controlling their bodies. This point is underlined by the haunting image of synthetic Joanna’s lifeless gaze, isolated in an extreme close-up, which looks out at the audience in the film’s final shot.

Interestingly, the film explores these themes of oppression and objectification on an aesthetic level too. Joanna’s job as a photographer complements her role as the inquisitive Gothic heroine although the agency Joanna enjoys through her control of the lens (along with her investigative abilities) is always compromised. Significantly, Joanna is not a successful photographer and the only pictures which garner critical interest are of domestic, family scenes. Instead The Stepford Wives emphasises how Joanna fails to look both in her capacity as a photographer, and metaphorically in her ability to see the truth about Stepford’s community. The point-of-view shots used to depict Joanna’s picture taking become ironic: Joanna’s control over these images (and, by extension, over what the viewer sees) is illusionary and transitory, and Joanna herself will quite literally be replaced by a body that has been made to fulfil an image which adheres to the standards set by the men’s desires. The moment Joanna discovers her automaton replacement reflects this usurpation of Joanna’s agency and her ability to look. When Joanna first enters the mock bedroom, her gaze is represented by a point-of-view shot which pans from left to right, scanning the room. Notably, this is the last time we see events strictly from Joanna’s perspective. Joanna’s discovery of the robot is depicted first through a close-up on Joanna’s face for a reaction shot, and then another pan (with accompanying aural cues) reveal the source of her horrified response. Joanna loses agency of the image at the moment when she comprehends Stepford’s sinister secret and will ultimately lose her life. Indeed, subsequent edits in the shot-reverse shots between Joanna and the android emphasise this connection between the film’s larger themes and its stylistic choices further: an edit frames a close-up on the double’s synthetic breasts, visible beneath the see-through negligee it wears. The camera’s voyeurism aptly reflects the triumph of the Men’s Association in objectifying the women of Stepford and controlling their bodies. This point is underlined by the haunting image of synthetic Joanna’s lifeless gaze, isolated in an extreme close-up, which looks out at the audience in the film’s final shot.

Thanks for such a great summary, Frances!

As ever, do log in to comment, or email me on sp458@kent.ac.uk to add your thoughts.