The group will be meeting in Jarman 7 on Wednesday 5th December 4-5pm. This will be a great opportunity to discuss the recent research seminars, and to plan future work.

20th November 2012, GLT3 5.30pm: Revisiting Tea and Sympathy (1956): Minnelli, Hollywood, Homosexuality

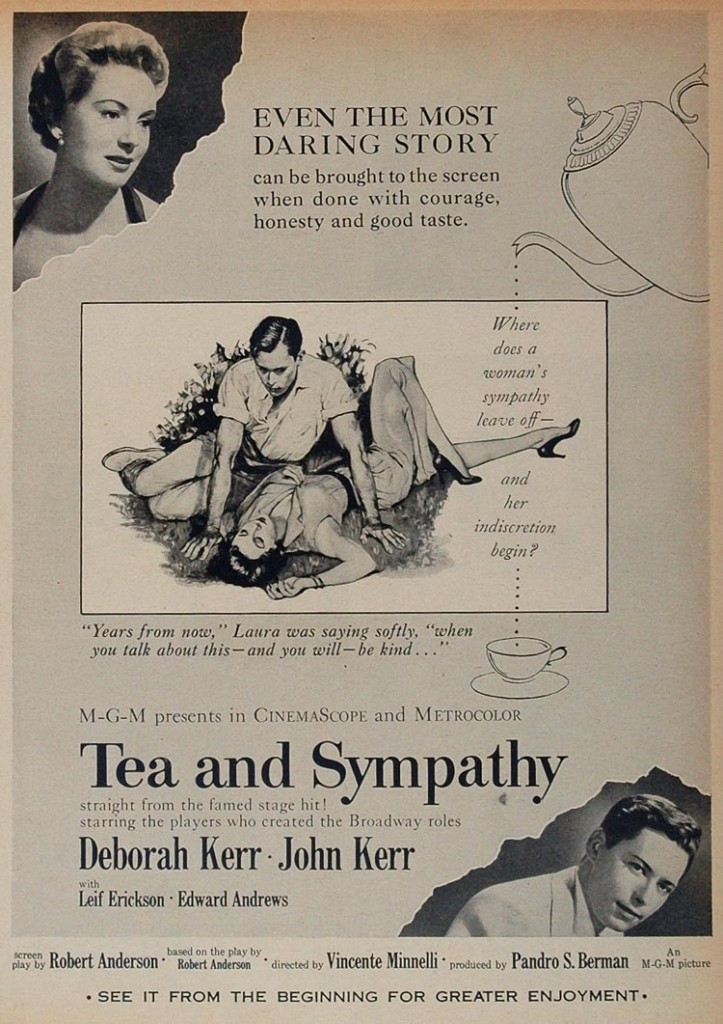

Above: A poster advertising Vincent Minnelli’s Tea and Sympathy (1956)

A still from Vincent Minnelli’s Tea and Sympathy (1956)

20th November 2012, GLT3 5.30pm

Dr Gary Needham, Nottingham Trent University

Revisiting Tea and Sympathy (1956): Minnelli, Hollywood, Homosexuality

Despite never once mentioning the word homosexuality, Tea and Sympathy nonetheless seems to say a lot about homosexuality in the 1950s. An effete young man, nicknamed ‘Sister Boy’ by his Fraternity, struggles with his unmanly ways only to be rescued by an older woman, the housemaster’s wife played by Deborah Kerr, who commits a sacrificial act of adultery in order to ‘cure’ his masculinity of its feminine ills. She tells him in the play/film’s most famous line: ‘Years from now when you talk about this, and you will, be kind’.

A minor, often forgotten work of Vincent Minnelli and 1950s Hollywood, Tea and Sympathy is known as a risible film that is often flagged up as key example of Hollywood’s disservice to homosexuality: it features heavily in The Celluloid Closet. Based on a successful Broadway play and released at the height of the ‘Lavender Scare’, Tea and Sympathy has been used in many an argument to illustrate a range of problematic assumptions, representations, and ideas around homosexuality and the regulatory and apparently regressive nature of Hollywood. Tea and Sympathy does confirm and conform to a number of these arguments, it caused trouble at MGM and is unquestionably problematic yet, as I will explore in this paper, there seems to something more complex and subtle going on in Tea and Sympathy: the simple misery it narrates is often contradicted by the mise en scene. Minnelli makes reference through film style to other closeted artists working in a mire of contradictions, for example, J. C. Leyendecker, central to the production of representations of American masculinity. Furthermore, a number of key scenes (‘beefcake on the beach’ and ‘fraternity pyjama fight’ mainly) tell us a good deal about the relationship between homosociality, homoeroticism, and Hollywood and the contradictions inherent in ideas that 1950s homosexuality was only visible and knowable as gender inversion.

30th October 2012, GLT2, 5.30pm: Acting and Behaving Like a Man: Rock Hudson’s Performance Style

Rock Hudson and Jane Wyman in Douglas Sirk’s Hollywood film Magnificent Obsession (1954)

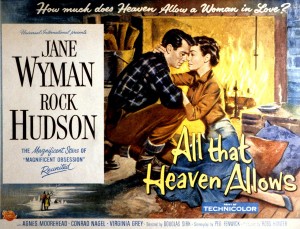

A poster advertising Rock Hudson and Jane Wyman in Douglas Sirk’s All That Heaven Allows (1955)

30th October 2012, GLT2, 5.30 pm

Dr John Mercer, Birmingham School of Media

Acting and Behaving Like a Man: Rock Hudson’s Performance Style

Rock Hudson is rarely considered to be one of the great film actors. Indeed it has become a popular legend that it took 38 takes for the young actor to deliver his only line in his 1948 debut FighterSquadron. At the height of his fame in the 1950s he was most often praised for his stoicism and persistence, consistently described, using a back-handed compliment, as the ‘hardest working actor in Hollywood.’

In 1946 the actor and writer Alexander Knox wrote an essay called ‘Acting and Behaving’ published in Hollywood Quarterly that discussed both stage and screen acting making a distinction between acting (the actor’s craft) and behaving (the performance offered by most film stars and for Knox at least an inferior activity.) In this paper I am using this broadly contemporaneous distinction to try and understand Hudson’s performances. My intention is in part at least an attempt to recuperate Rock Hudson as an actor and to make a case for the study of the type of performance style that he is associated with.

As a successful Hollywood star Hudson was to perform in roles that defined the ideals of mid 20th century American masculinity in effect he was the epitome of heteronormativity. Working with a variety of directors and across a diverse range of genres from westerns to war film, melodrama to romantic comedy Hudson illustrated what it meant to be a man.

Initially self-taught, Rock Hudson learnt his craft ‘on the job’ aiming for a naturalistic style. He took to heart Raoul Walsh’s early advice; “Don’t try to act…Remember up on that screen you’re magnified forty times. Be natural, underplay and it will look great.” The performance style that Hudson was to become associated with allows for an especially limited and circumscribed expressive range for a male actor and consequently the need for nuance is paramount. Hudson’s performances then can be understood as a form of ‘behaving’. My argument in this paper is that the ‘behaving’ that Hudson demonstrates in his films is a very refined form of performance doubly complicated by the details of his personal life.

In this paper I will explore Hudson’s ‘behaving’ in Written on the Wind (1956) and other films by Douglas Sirk.

This Term’s Events

Charles Boyer and Ingrid Bergman in George Cukor’s Hollywood film Gaslight (1944)

Two exciting upcoming events this term…

On 30th of October Dr John Mercer of Birmingham School of Media will give a research seminar entitled ‘Acting and Behaving Like a Man: Rock Hudson’s Performance Style’…

On 20th of November Dr Gary Needham of Nottingham Trent University presents on ‘Revisiting Tea and Sympathy (1956): Minnelli, Hollywood, Homosexuality’

Please see our Events page for more details, including times and venues…