Rock Hudson and Jane Wyman in Douglas Sirk’s Hollywood film Magnificent Obsession (1954)

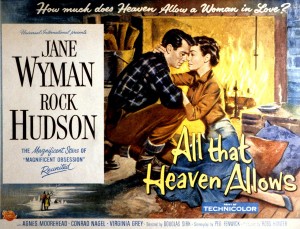

A poster advertising Rock Hudson and Jane Wyman in Douglas Sirk’s All That Heaven Allows (1955)

30th October 2012, GLT2, 5.30 pm

Dr John Mercer, Birmingham School of Media

Acting and Behaving Like a Man: Rock Hudson’s Performance Style

Rock Hudson is rarely considered to be one of the great film actors. Indeed it has become a popular legend that it took 38 takes for the young actor to deliver his only line in his 1948 debut FighterSquadron. At the height of his fame in the 1950s he was most often praised for his stoicism and persistence, consistently described, using a back-handed compliment, as the ‘hardest working actor in Hollywood.’

In 1946 the actor and writer Alexander Knox wrote an essay called ‘Acting and Behaving’ published in Hollywood Quarterly that discussed both stage and screen acting making a distinction between acting (the actor’s craft) and behaving (the performance offered by most film stars and for Knox at least an inferior activity.) In this paper I am using this broadly contemporaneous distinction to try and understand Hudson’s performances. My intention is in part at least an attempt to recuperate Rock Hudson as an actor and to make a case for the study of the type of performance style that he is associated with.

As a successful Hollywood star Hudson was to perform in roles that defined the ideals of mid 20th century American masculinity in effect he was the epitome of heteronormativity. Working with a variety of directors and across a diverse range of genres from westerns to war film, melodrama to romantic comedy Hudson illustrated what it meant to be a man.

Initially self-taught, Rock Hudson learnt his craft ‘on the job’ aiming for a naturalistic style. He took to heart Raoul Walsh’s early advice; “Don’t try to act…Remember up on that screen you’re magnified forty times. Be natural, underplay and it will look great.” The performance style that Hudson was to become associated with allows for an especially limited and circumscribed expressive range for a male actor and consequently the need for nuance is paramount. Hudson’s performances then can be understood as a form of ‘behaving’. My argument in this paper is that the ‘behaving’ that Hudson demonstrates in his films is a very refined form of performance doubly complicated by the details of his personal life.

In this paper I will explore Hudson’s ‘behaving’ in Written on the Wind (1956) and other films by Douglas Sirk.