Denizens of the Real World often picture researchers of print culture as perpetually cooped up in stuffy libraries, inhaling centuries-old dust and the stale whiff of foxing paper. For a large amount of the time this is a representative tableau (and long may be it so!), but another important part of our job is to venture out and tell others about our findings. If you are as lucky as we are, you get to travel quite a bit when doing so. In my last post, I discussed my inspiring visit to Trondheim, and I announced that we would soon be crossing the Channel for a workshop at Ghent University. As we expected, this event of Friday 30 October was a great success as well, not least because of the warm welcome that we received from our friends at the English section of the Ghent Department of Literary Studies. We heard from fabulous PhD students and postdocs based at Ghent and Kent about their research on periodicals, we presented our own work, and were introduced to the great new Ghent project ‘Agents of Change: Women Editors and Socio-Cultural Transformation in Europe, 1710-1920’, funded by the European Research Council.

Several grad students took part as well, and another highlight of the day was a lecture by Prof. emer. Laurel Brake (Birkbeck), who drew from her vast knowledge and experience to introduce these periodical padawans to our discipline. Prof. Brake has been an influence on my thinking since I first got into periodical studies, and although she was self-effacing in her talk, it was impossible to miss how many ideas pioneered by her have since been interiorized by the entire field. To give but a few examples, the special issue on the uses of theory in periodical studies that she edited for Victorian Periodicals Review in 1989, and the essay collection Investigating Victorian Journalism (1990 – with Aled Jones and Lionel Madden) that is still the best primer on the subject, have pushed the field forward in ways that cannot be overstated. In her much-cited Print in Transition, 1850-1910: Studies in Media and Book History (2000), she helped to instigate a material turn in studies of ‘print culture’; a multidisciplinary approach that, incidentally, she was one of the first scholars to name as such. Though their case studies are Victorian, these publications can all be used as a basis for studies of eighteenth- and early-nineteenth-century periodicals as well.

since I first got into periodical studies, and although she was self-effacing in her talk, it was impossible to miss how many ideas pioneered by her have since been interiorized by the entire field. To give but a few examples, the special issue on the uses of theory in periodical studies that she edited for Victorian Periodicals Review in 1989, and the essay collection Investigating Victorian Journalism (1990 – with Aled Jones and Lionel Madden) that is still the best primer on the subject, have pushed the field forward in ways that cannot be overstated. In her much-cited Print in Transition, 1850-1910: Studies in Media and Book History (2000), she helped to instigate a material turn in studies of ‘print culture’; a multidisciplinary approach that, incidentally, she was one of the first scholars to name as such. Though their case studies are Victorian, these publications can all be used as a basis for studies of eighteenth- and early-nineteenth-century periodicals as well.

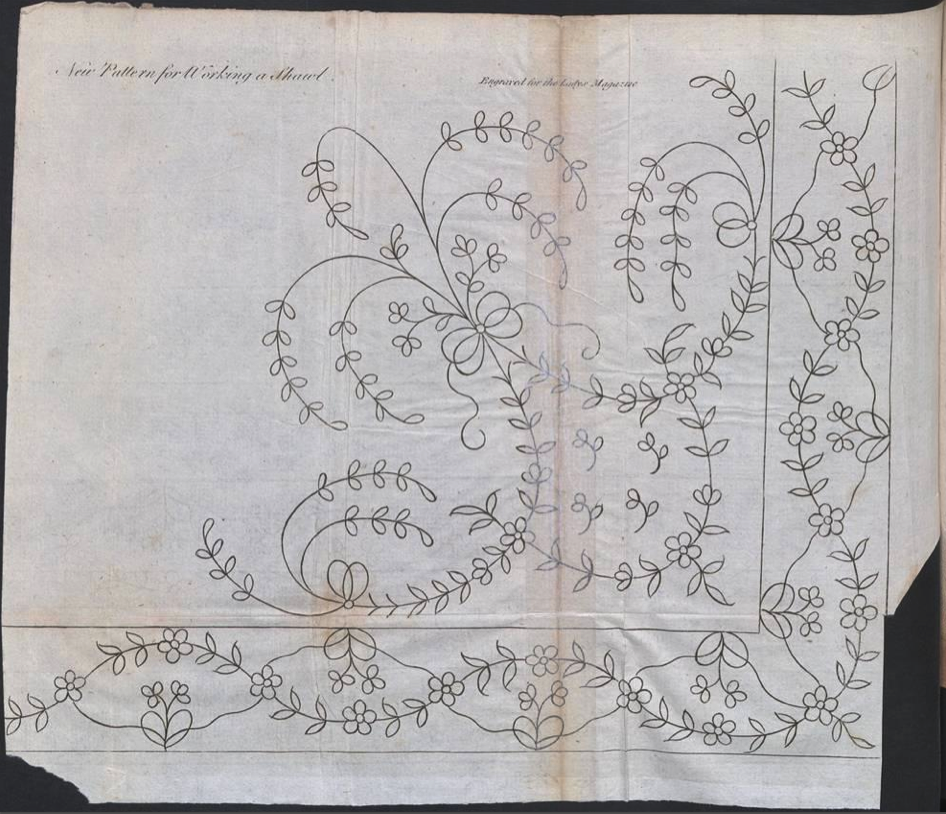

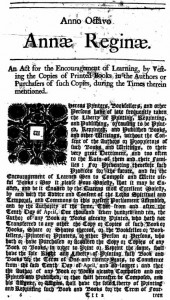

Prof. Brake reminded us that now, when most scholars mainly read periodical texts in digital form, we need to be more aware than ever of the material aspects of the texts that we are studying. She recommends using the digitizations as conveniently accessible databases, but rightly urges us to return regularly to the original paper copies. Even when I snuggle up with a printed text, I have found it to be vital to question what I am looking at. As we have noted before, monthly magazines have mostly been handed down to us in annual volumes bound for private or public libraries, or sold in such sets by the publishers themselves at the end of each year. In the case of the Lady’s Magazine, only a few original monthly issues have survived at all. The problem is that annual volumes tend to have been purged of paratextual matter such as wrappers and other addenda (fashion plates, music sheets, tipped-in frontispieces, loose supplements, etc.). Usually digital holdings consist of scans from these annual volumes rather than the (often lost) original monthly issues, and this is not always apparent from the databases’ interface.

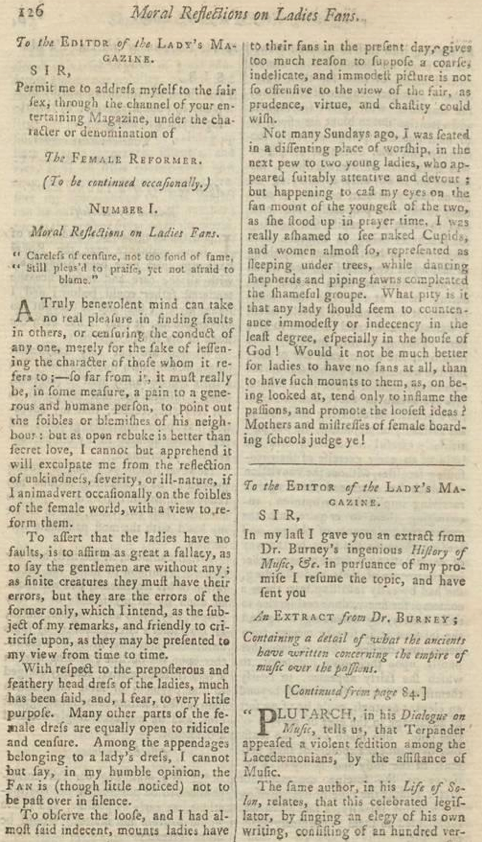

In what follows I would like to look at two sources of bibliographical information that are inevitably lost through the standardized formatting of digital databases. After the efforts of Prof. Brake and others, attention to material details such as size and bindings have become a regular interest in nineteenth-century periodical studies, but it is probably fair to say that – a few admirable exceptions notwithstanding – this has been less the case for the eighteenth century. I will here offer a few notes on how ogling and fondling paper copies of the Lady’s Magazine allows us to compare it to other periodicals of its time, thereby helping us to situate it within the market.

When you read the magazine in its excellent digitization by Adam Matthew Digital, it will of course always be as large as your screen. From this you cannot gauge how large or small this periodical actually was, and this is one of those rare cases where size does matter, because it not only affects the production costs, but also makes the magazine either look like its competitors or stand out amongst them. Bibliographers recommend stating exact measurements in inches or centimetres (width x length) when describing the size of texts, because the traditional terms for formats, such as folio, quarto, octavo, duodecimo, are more slippery than you might think. It is easy to confuse (quoth the immortal Fredson Bowers) the inexact ‘commercial format’ referring to conventions of page size that differs between countries and historical eras, and the complicated ‘bibliographical format’ that is a technical categorization based on the number of foldings of (and hence the number of pages out of) the printed sheet.[1] Its size varies slightly over the years, but the Lady’s Magazine is around 5 and 1/8 inches by 8.5 inches large, placing it between what are usually described as a duodecimo and an octavo, and roughly at the same size as the market-leading Gentleman’s Magazine. As Calhoun Winton writes about the two most regular formats for periodicals of the earlier eighteenth century, ‘[i]f the duodecimo was designed for the literary walker, who carried books in his pocket, the octavo was for the carriage trade’.[2] The Lady’s Magazine no doubt adopted this format to emulate the Gentleman’s, which in turn will have favoured it because it was economical for the publishers, who could that way get a lot of pages out of a ream of paper. This helped to keep the price down. However, it is true that the magazine was easily portable, and at an average length of 60 pages, it made for light reading in the most literal sense.

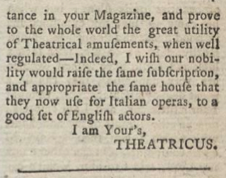

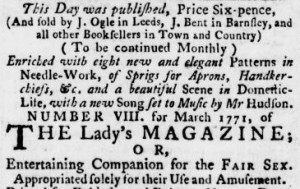

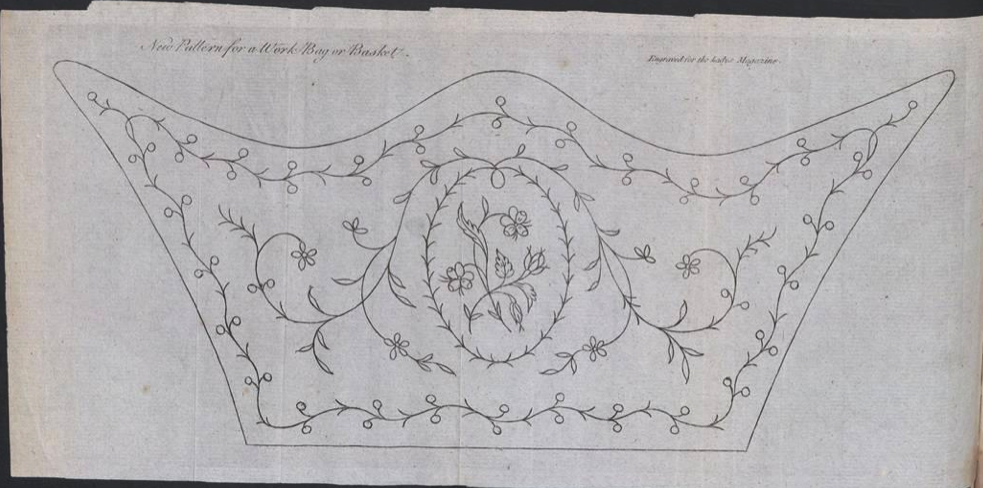

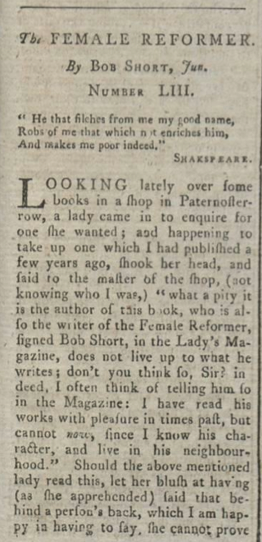

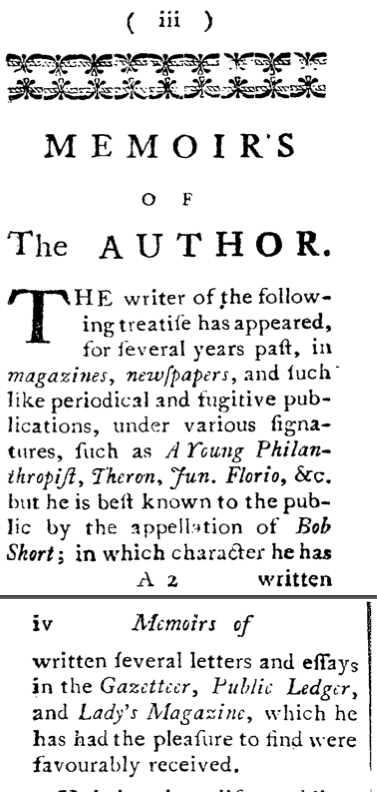

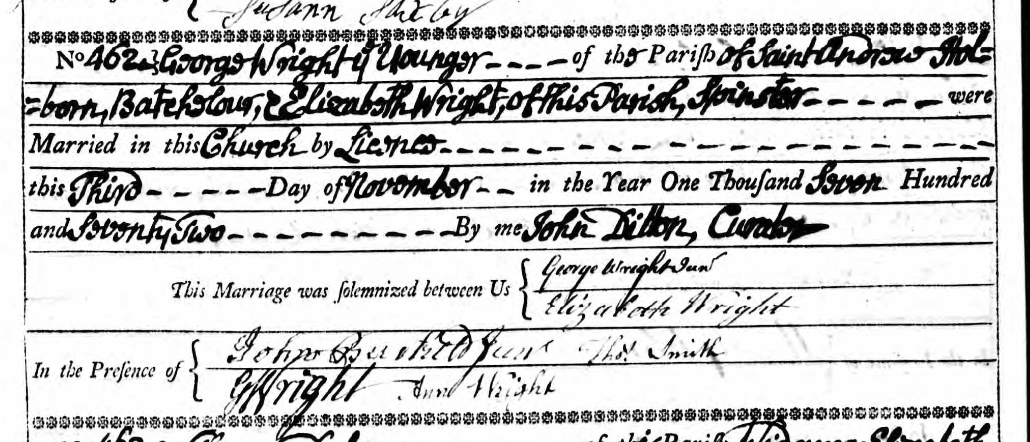

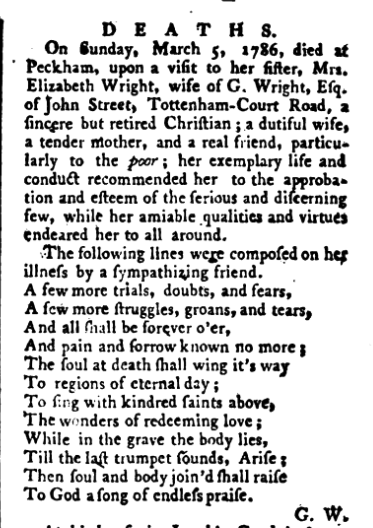

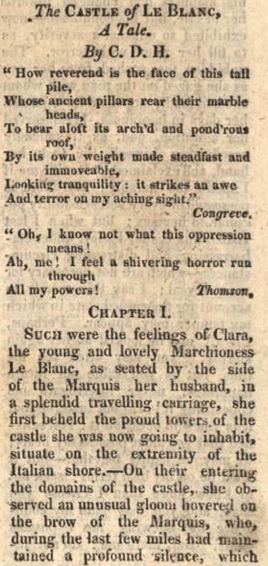

The bindings of a publication should always be considered as well, because as the first and most tactile point of contact between the reader and the text they will be designed to convey vital information. In the nineteenth century some more expensive and prestigious periodicals would come bound like books with hard covers, the durability of these boards metonymically suggesting less ephemerality for the bound publication than would be associated with allegedly disposable publications that came in comparatively flimsy paper covers. In the eighteenth century this practice was close to non-existent, and it made no sense anyway for periodicals that were meant to appeal to a wide audience, like the Lady’s Magazine. As you would expect, the paper covers, or wrappers, of monthly magazine issues too are absent from the annual volumes. Monthly issues of the Lady’s Magazine are rare, but rarer still are copies that still have their wrappers. A largely intact copy of the 1771 October kept in the special collections of the Kent Templeman library comes with the original cover, so we do at least know what it looked like at this point. This particular wrapper on its front just features a table of contents, and on the verso of the front as well as on both sides of the back, it has advertisements. The latter are an invaluable addition to our knowledge of the Lady’s Magazine’s market position because the only adverts within the main body of the magazine are for the Lady’s Magazine itself. We will return to this paratextual advert section in a future blog post as this would take us too far here.

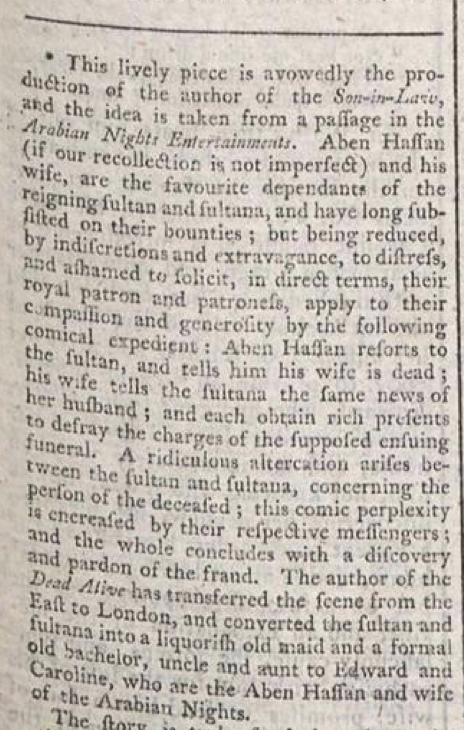

The table of contents on the 1771 wrapper may not sound very exciting, but it is not without its uses. From January 1774 (Vol. V) these tables of contents, with the same layout, appear within the parent publication, so this suggests a change in marketing strategy whereby from this issue onwards the wrappers no longer list the contents, but maybe get a more eye-catching design instead. Until we find post-1773 wrappers we of course do not know for sure, but some may pop up sooner or later. Please do give us a shout if you ever spot one!

Dr. Koenraad Claes

School of English, University of Kent

[1] Fredson Bowers, Principles of Bibliographical Description (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1994), p. 429

[2] Calhoun Winton, ‘The Tatler: From Half-Sheet to Book’, Telling People What To Think: Early Eighteenth-Century Periodicals from The Review to The Rambler, Ed. by J. A. Downie and Thomas N. Corns (London: Routledge, 1993), p. 30