In the 1830s, in India, an anonymously published book entitled Santa Sebastiano was sold at auction. It had two eager bidders who did not want to give up the purchase. One was Emily Eden, poet, novelist, bibliophile and sister of Lord Auckland. The other was historian, politician and equally avid reader Thomas Babington Macaulay. The episode is described with predictable bemusement by Macaulay’s nephew Sir George Trevelyan in his Life and Letters of Lord Macaulay (1875-76), who notes that the auction winner, Macaulay, later annotated the last page of his copy of Santa Sebastiano (1806) with ‘an elaborate computation of the number of fainting-fits that occur’ in it. (Julia de Clifford alone faints 11 times, but who, except Macaulay, is counting?) [1]

While Trevelyan expressed admiration that Macaulay thought he could probably ‘rewrite “Sir Charles Grandison” from memory,’ his uncle’s passion for ‘silly, though readable’ books, like those of Mrs Meeke or Mrs Kitty Cuthbertson, who authored Santa Sebastiano, as well as The Romance of the Pyrenees (1803), The Forest of Montalbano (1810), Adelaide; or, the Countercharm (1813), and (although Trevelyan did not know this) Rosabella; or, A Mother’s Marriage (1817), seemed inexplicable. Yet Trevelyan’s view is unrepresentative. Kitty or Catherine Cuthbertson was a widely read and highly popular Gothic novelist in the Radcliffean tradition. The Romance of the Pyrenees was translated into French and German (the anonymous French translation was widely presumed to be of a Radcliffe novel on the continent). American editions of her novels followed and extracts from them appeared in US periodicals well into the nineteenth century [2].

A perhaps still more telling indication of Cuthbertson’s enduring popular appeal can be found in a review of Lord Brabourne’s edition of Jane Austen’s letters that appeared in The Times on 6 February 1885. The review broadly welcomes Brabourne’s edition, but laments the lack of annotation, especially in correspondence in which Austen alludes to other writers. It was ‘absurd to assume’, the reviewer declared, ‘that one reader in a thousand knows any particulars about “Alphonsine” and the “Female Quixote”, and is aware that Madame de Genlis is the author of the former and Mrs. Charlotte Lennox of the latter’. The refrain is repeated a few lines later when the reviewer turns to a now well-known letter in which Austen expresses incredulity that Mrs. (i.e. Jane) West was so very prolific when so domestically encumbered. West, the reviewer proclaims, is ‘but a name to the reader of this work’. Brabourne should have recognised this fact and provided relevant editorial information that the reviewer is, instead, forced to disclose. West, he interestingly continues, was ‘a voluminous writer in the last century who resembled in many things the Mrs. Meeke and Mrs. Kitty Cuthbertson’ [3].

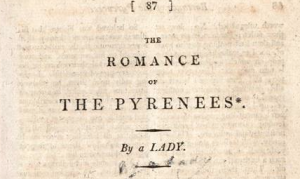

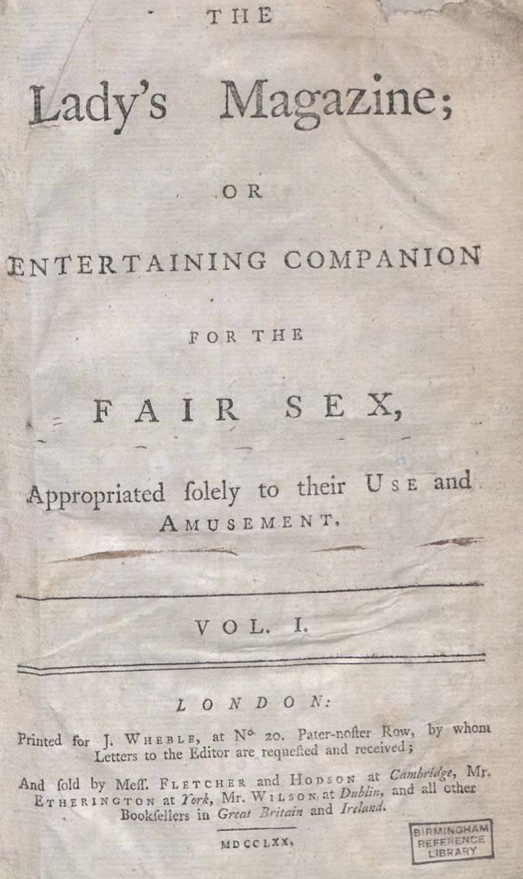

LM, 35 (Feb 1804): 87. Image © Adam Matthew Digital / British Library. Not to be reproduced without permission.

What does this tell us? Well, for thing it suggests that if West and her works were obscure in 1885, Cuthbertson and her Gothics evidently were not. This is despite the fact that Cuthbertson never signed her name to any of her novels. And there is considerable evidence that knowledge of her fiction, although increasingly clouded in a biographical fog, persisted for at least several decades afterwards the Times review. Cuthbertson’s novels generated sufficient interest, for example, to spark conversations in Notes and Queries the 1910s and 1920s (some prompted by speculations that her work was by Radcliffe or Clara Reeve). More recent scholarship on the Gothic by Rictor Norton and others has sought to establish Cuthbertson’s place as one of the key figures of the genre in the early nineteenth century, as she surely was [4].

It was a career that began in earnest in the pages of the Lady’s Magazine. (Some sources suggest that she wrote an earlier 1793 unpublished play staged on 25 February at Drury Lane entitled Anna but the attribution is not secure.) Her first novel, The Romance of the Pyrenees was serialised in the magazine from February 1804, having been recently published in volume form by Robinson (the magazine’s publisher) in 1803. However, just weeks after the title first went on sale, and after only a few copies of it had been sold, the bulk of the print run of the Romance was devastated by a warehouse fire at the establishment of the magazine’s then printer, Samuel Hamilton.

LM, 35 (Feb 1804): 87. Image © Adam Matthew Digital / British Library. Not to be reproduced without permission.

Attempting to cut their losses on the damaged run, Robinson decided to serialise Cuthbertson’s novel along with their recently printed edition of Royall Tyler’s American 1797 The Algerine Captive in the Lady’s Magazine with occasional engravings. As a consequence, The Romance of the Pyrenees reached a new and possibly much wider readership than it would have done had it been published in volume form alone. It became the longest running serial magazine fiction in the long eighteenth century apart from a serialisation of Pamela [6]. In subsequent years, the magazine would publish extracts of other of her novels (Santa Sebastino in 1807; Adelaide in 1814), all of which Robinson published, and the snippets from which seemed to serve as puffs to promote wider circulation of her work.

Cuthbertson’s fiction, with its complex plots and naturalised supernatural endings (my favourite involves a parrot), extends over many volumes and merits a blog post in its own right. Since reading it, however, one of my major preoccupations has been trying to find out more about its author. Although Cuthbertson was evidently popular and, at some point in the nineteenth century, revealed to be the author of her anonymous novels, her biography remains a series of speculations and lacunae.

Biographical accounts suggest that Cuthbertson was born before 1780 and that she may have been Scottish or, as a likely army daughter, been born overseas. Some sources also make reference to a possible connection to a Captain Bennet Cuthbertson, who published an important work on military tactics. Armed with this scant information I was determined to find out more and with a little effort, and a few hours lost in the archives, I did.

The first and most signifiant clue I found was a Notes and Queries article by a relative of the Cuthbertsons, William Ball Wright, of Osbaldwick Vicarage, York, who posted in June 1911 a response to a query about the authorship of the Romance of the Pyrenees. The article notes that Kitty Cuthbertson was the author of the work and that Kitty’s father was a Captain Bennet Cuthbertson, of Northamptonshire, of the 5th Regiment, who retired to Dublin in 1772. The first two dots were, therefore, joined. A third came when I looked into Bennet Cuthbertson a little more. Cuthbertson‘s System for the Complete Interior Management and Oeconomy of Battalion of Infantry was published in 1768 in Dublin. Likely before the publication of this work, Cutherbertson married a Catherine Bell (daughter of a Dr Thomas Bell of Dublin). Ball Wright, a descendant of Catherine Bell’s sister, Elinor, goes on to explain that the couple had several children, including Kitty (or Catherine), Olivia, Julia and Anne. (It is possible that they also had a son, Robert, although this is not mentioned in the article.) While Anne stayed in Ireland, the other Cuthbertson sisters moved to London at some unknown point before 1803 to ‘wr[i]te romances’. [5]

The Dublin connection, then, is what has thwarted efforts to find Catherine Cuthbertson before now. The Irish records for this period are patchy to say the least. After many hours of searching, I can find no birth or baptism notice for Catherine in the extant Irish records. But I can now prove that she was born in Ireland.

Hoping that a life of penning Gothic fiction promoted good health, long-livedness and a disinclination to marry, I went in search of the Cuthbertson sisters in the 1841 and 1851 census returns. An Olivia Cuthbertson (born in Dublin) showed in the 1851 census as living, aged 85, in Ealing, Middlesex. I was disappointed that I couldn’t find a Catherine or Julia. But the Ealing connection seemed worth pursuing. What if this Olivia was Catherine’s sister? And what if the sisters had lived together or very near one another?

And then I found them.

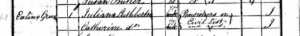

In the 1841 census, Catherine Cuthbertson, born in Ireland, was living with a Juliana Cuthbertson. Both are listed (perhaps improbably) as 70 years old at the time (although it is theoretically possible, if unlikely, that the sisters were twins). Their source of income was the Irish Civil List, details of which subsequently confirmed for me that the sisters, along with Olivia, were living off their deceased father’s pension. I then went in search of Catherine’s death notice (occurring some time between 1841 and 1851, since she was not in the later census) and soon found a burial record indicating that she was buried in Ealing on the 2 June 1842 aged a more likely 67, dating her birth to around 1775.

As attribution finds go (and we have had lots so far in the Lady’s Magazine project), this may not seem like headline news. Cuthbertson was a magazine contributor by accident not design. And although her work in the magazine and outside it was published anonymously, her authorship has long since been known and the attributions of her novels secured. Putting a (rough) birth and (more secure) death date on Cuthbertson’s life as I have been able to do might seem more like housekeeping than significant research.

But I can’t help but feel that this is signficant. The Dublin connection – the fact of which made Cuthbertson’s biography so remote to us for so long – is surely of particular interest. Cuthbertson deserves the place in the history of the Gothic she is beginning to secure, but she also, I think, warrants a place in the history of Irish (women’s) writing. I hope some of my colleagues in Irish Studies will pick up this gauntlet and run with it, because Cuthbertson, quite frankly, deserves our attention.

Like so many of the writers published in the Lady’s Magazine Cuthbertson’s work was influential. She was more than a Radcliffe imitator. Her work, as I hope to show in a later blog post, had formal and thematic influence and, as I have indicated, had extraordinary geographical as well as temporal reach. Her books sat alongside Austen’s in Queen Charlotte’s library, and as we have seen, it was taken for granted that readers in the 1880s would have heard of her, as they would have heard of Jane Austen, in contrast to the by then considered obscure Jane West, Charlotte Lennox and Madame de Genlis. Into the early twentieth century, people cared enough about her novels to enquire into her author’s life and work.

Cuthbertson, like so many Lady’s Magazine authors, is an important figure in literary history, not just because of what she wrote, how many people fainted in her novels’ pages, or because people like Macaulay read her. She is important because her persistent popularity and claim on readers’ imaginations makes clear that so many of the things we once thought we knew about literary history – about who was read and remembered – don’t always chime with reality.

Dr Jennie Batchelor

School of English

University of Kent

Notes

[1] Sir George Trevelyan, The Life and Letters of Lord Macaulay, 2 vols. (New York: Harper and Brothers, 1877), vol 1, pp. 129-130.

[2] A notice for an 1812 American edition of The Forest of Montalbano appeared in the National Intelligencer for 24 March 1812, for instance. The Arkansas Gazette published a long extract of Romance of the Pyrenees on March 17 1878.

[3] ‘Jane Austen’, The Times (6 Feb 1885): 3.

[4] See, for instance, Rictor Norton ‘Gothic Readings’ <accessed 14.4.16>.

[5] William Ball Wright, ‘Note’, Notes and Queries, 77 (17 June 1911): 475.

[6] Robert D. Mayo, The English Novel in the Magazines, 1740–1815 (London: Oxford University Press, 1962), pp. 232–33

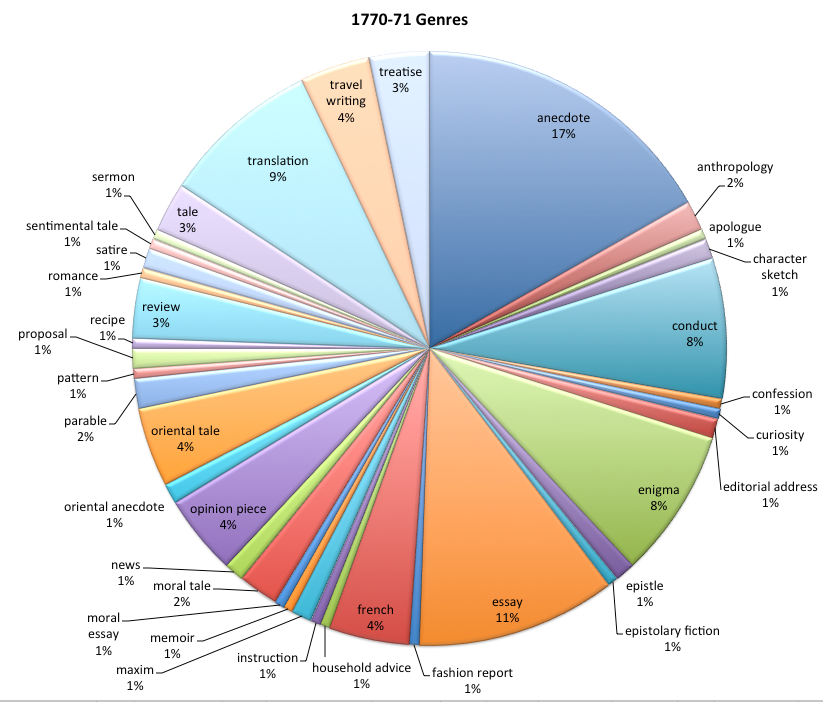

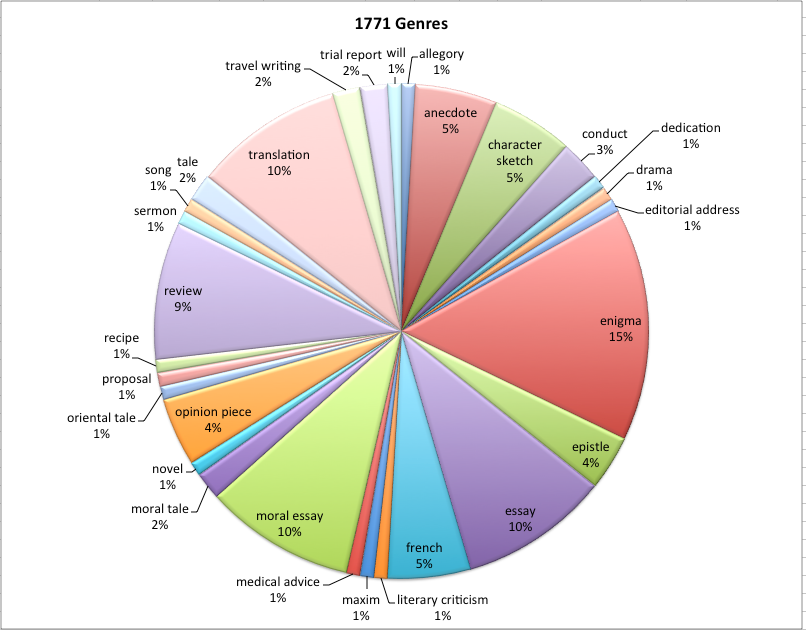

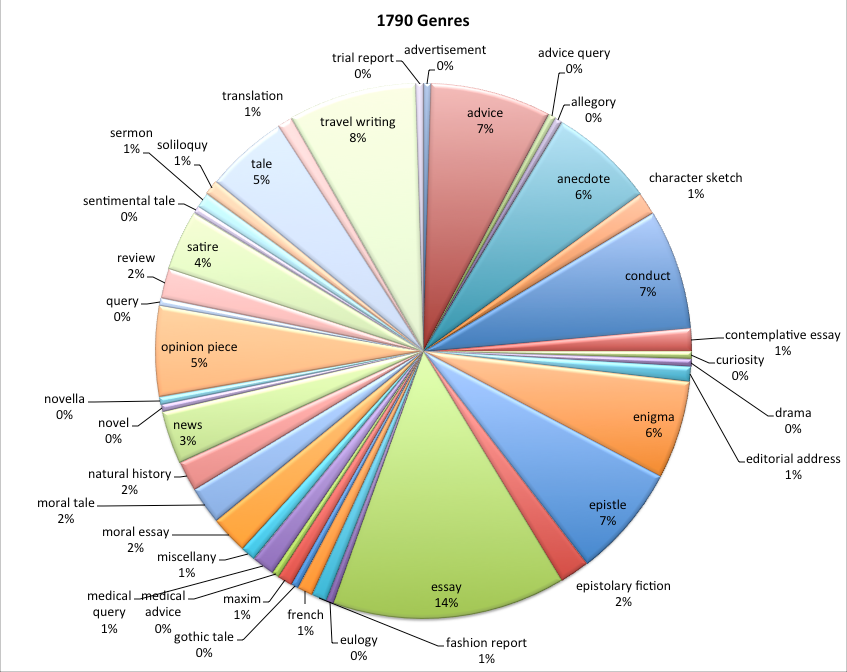

We often discuss the variety of items, subjects, themes and genres that appear in the Lady’s Magazine. Each seemingly transparent topic can be found within an array of genres; for example, the topic of ‘fashion’ appears in items ranging from the moral essay and advice column to the opinion piece, historical essay and fashion report. Deciding which genre an item belongs to in the magazine is a task at times difficult to negotiate. This is in part because genres overlap and are by nature flexible; designating a particular item either a sentimental tale or a moral tale is thus not always simple or clear. Assigning works a genre requires that one privilege a particular genre over another, making decisions at once about authorial intent, editorial preference and reader perceptions.

We often discuss the variety of items, subjects, themes and genres that appear in the Lady’s Magazine. Each seemingly transparent topic can be found within an array of genres; for example, the topic of ‘fashion’ appears in items ranging from the moral essay and advice column to the opinion piece, historical essay and fashion report. Deciding which genre an item belongs to in the magazine is a task at times difficult to negotiate. This is in part because genres overlap and are by nature flexible; designating a particular item either a sentimental tale or a moral tale is thus not always simple or clear. Assigning works a genre requires that one privilege a particular genre over another, making decisions at once about authorial intent, editorial preference and reader perceptions.