Already several of our blog posts have discussed the many instances of appropriated content in the Lady’s Magazine. In my last post, I discussed the methodology by means of which I try to find the sources of these non-original items, and a few kind readers have since humoured me by asking about my findings. Of course, everything will be revealed in our index, but I would be happy to divulge a little more here, by looking at some discernible tendencies in the first ten volumes of the magazine (1770-1779), comprising the first 3,173 entries in the index.

As most periodicals of its day, and particularly those in the ‘magazine’ category, the Lady’s Magazine continuously lifted content from other publications. Often these were complete and verbatim reprints, but there were also countless extracts from books and from larger contributions to other periodicals, that were furthermore regularly edited or paraphrased, or assembled into Frankensteinian collages of extracts that together form one (not always seamless) larger feature. Reader-contributors as well as editors heartily took part. After I dropped a P-bomb in one post of last year, the three of us and some of our favourite readers had a productive debate within this blog and on Twitter (@ladysmagproject) on whether ‘plagiarism’ was a suitable word for this practice, and decided that we would avoid it, in favour of the more neutral ‘appropriations’. The term ‘plagiarism’ was occasionally used in the Lady’s Magazine, seemingly in the sense that we use it today, but like other authorship scholars we are wary of oversimplifying an inevitably complicated situation by applying a damning term to what really was a very common practice.

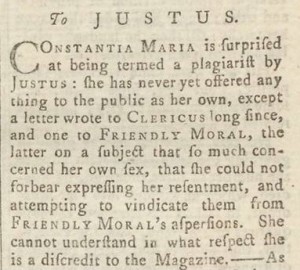

LM VIII (July 1777): p. 377. Image © Adam Matthew Digital / Birmingham Central Library. Not to be reproduced without permission.

In most cases, appropriation was not problematic from a legal point of view, although the ways in which it happens suggest some ethical misgivings on the part of the appropriators. The Lady’s Magazine’s extracts often do not have an attribution (identification of an author) or ascription (citation of a source) and hardly ever have both; sometimes they are surreptitiously detached from their original authors and publication context by means of spurious signatures, and sometimes translated, paraphrased or edited so as to make them seem entirely new. Adapted appropriations can be difficult to spot, but one develops a sort of fondness for the intricacy of this intellectual theft. You may have seen a similar thing happen to police detectives on crime shows.

Finding sources for content that you suspect to have been appropriated does get easier after a while, because certain patterns arise that are dependent on the fluctuating prestige of the sources or the popularity of certain genres and themes. It is important to understand that then as now, magazines were business ventures, and editors value efficiency in their task to fill their publications with content that the readership will appreciate. The editors and enterprising reader-contributors of the Lady’s Magazine regularly went to work a-cutting and a-pasting themselves, and it will come as no surprise, for instance, that soon after two book-length eyewitness accounts of Captain Cook’s travels appeared in 1777 (Cook’s own A Voyage Towards the South Pole, and round the world and George Forster’s A Voyage around the World), several extracts from both are published. For topical sources like these, where the name arguably was a selling point and nobody would be fooled by a tacit appropriation anyway, due attributions and ascriptions tend to be included. Recent books in general, especially when issued by the Lady’s Magazine’s publisher Robinson, were more likely to get some bibliographical details, in keep with the secondary function of the magazine as a ‘miscellany’ that digested recent publications as a service to the reader. Newspaper accounts of famous court cases were as a rule reprinted without citation because news coverage in those days was considered at everyone’s disposal, but during the American Revolutionary War the governmental London Gazette is respectfully cited when the Lady’s Magazine takes up its dispatches. This may have been done out of patriotic deference to this institution and because of the authority carried by the source.

For older source texts there does not seem to have been a consistent attribution policy. Correspondence columns in the magazine indicate that the editors were regularly duped by reader-contributors passing off work by others as their own, but because the appropriation practices are so similar and we know so little about the magazine’s personnel, it is rarely possible to tell which signatures refer to staff writers and which to readers. Sometimes essays from The Spectator, over 60 years old at that point, were extracted from without any mention of their provenance, for instance in the essay ‘Sketches of the whole duty of women’ (Suppl. 1777), signed ‘T.’, which is in fact a verbatim lift from The Spectator No. 342 (2 April 1712). Other items do give credit to ‘Mr. Addison,’ or to ‘Dr. Goldsmith’ (whose essay periodical The Bee of 1756 to 1759 however is pirated several times too).

Confusingly, as content circulated (almost) freely through the press, we need to distinguish between what I have come to call ‘direct appropriations’, taken straight from the ultimate source, and ‘appropriated appropriations’ (for want of a better term). Extraction necessitates a process of selection, and it is hard work to read through a great number of old or recent publications to get to suitable bits, so it was a lot quicker if someone else had done the selecting for you. The two most recurrent types of sources in the first ten volumes are publications that do just that.

The most common sources for appropriation are other periodicals. You should not feel sorry for them: they gave as good as they got and many borrowed from the Lady’s Magazine in turn. When you are selling your wares in a market you want to keep track of the competition, and in the case of the Lady’s Magazine that meant other successful titles catering for a socially and ideologically diverse audience. Which competitors a periodical appropriated from can tell you a lot about its marketing strategy, although in these cases there is only rarely any acknowledgement of the source. The most common source for identified appropriations from periodicals is the Gentleman’s Magazine (1731-1922), the pioneering publication in the magazine genre in Britain that was probably the bestselling periodical in these isles for the first century of its existence. The second most regular periodical source is the Gentleman’s closest early contender, the first London Magazine (1732-1785). It takes all kinds of items from these two publications and others like it, ranging from letters to the editor to poetry. Because these publications from their earliest numbers included circulating content too, the Lady’s Magazine often copied from them not second-hand, but third-hand or maybe even fourth-hand material. I have found instances where other periodicals subsequently took this up from the Lady’s Magazine, and a chain of appropriations continued that could last for over a hundred years.

Interestingly, as with the essay periodicals mentioned above, decades-old pieces were often chosen. The fact that sometimes, in the same period, several items from the same volume of an older periodical are reprinted in the Lady’s Magazine, implies that the staff writers when pressed for copy (true to the evocative eighteenth-century image of the ‘hack’) would randomly open an old volume and start extracting. It happens very often that an extract is printed – again often without any mention of its being an extract in the first place – that is traceable to an ultimate source (a book), where suspiciously the extract corresponds to a quote given in an article on the book in question. Essays on books in the Critical Review and the Monthly Review are regular targets.

For instance, in December 1778 the anecdotal piece ‘Striking instances of the charitable character of Madame de Maintenon’ appears in the Lady’s Magazine, without signature. It turns out that this item was extracted from Memoirs for the history of Madame de Maintenon and of the last age (1757), a translation by Charlotte Lennox of the French original by Laurent Angliviel de La Beaumelle (1755). The plot thickens: the exact same passage is quoted in an article on that book which appeared in the Critical Review 2.4 (April 1757). It is more than likely that the Lady’s Magazine staff writer who provided this item had not even gleaned it straight from the book, but just made off with the bite-sized morsel conveniently provided in Tobias Smollett’s periodical. For extracts from recent and more topical books, the magazine often turned to the then most recent issue of the Annual Register (1758-), of which the main interest was that it itself had selected the most noteworthy publications of the past year, and, conveniently for the Lady’s Magazine, it too often featured generous quotations.

The second most common sources for appropriation are reference works. As we are still in the so-called ‘Age of Enlightenment’, encyclopedic works were popular, and these seem to have been the most frequent ultimate sources of the countless historical anecdotes and popular-scientific (mostly geography and natural history) items that appeared in late-eighteenth-century magazines. These reference works are tricky to trace with certainty, because just like periodicals they are to a large extent composed of foraged content, usually being a patchwork of translated bits from French sources and pirated older sources on the same topic. To an eighteenth-century magazine editor, extracts are like potato crisps: it’s difficult to have just one. When the Lady’s Magazine ‘discovers’ a useful reference work, it tends to make the most of it, and sometimes uses it without acknowledgement to supply an entire series. In 1771, to give but one example, the series ‘The Lady’s Biography’ consisting of potted histories of the lives of famous women from Herod’s wife Mariamne to Mary Queen of Scots, is entirely lifted from the anonymous Biographium Faemineum: The Female Worthies (1766).

We are of course not the only researchers who are fascinated by appropriation. Jenny and I, joined by our Kent colleague Dr. Kim Simpson, will have a panel on ‘Appropriation as cultural transmission in the eighteenth-century periodical press’ at the upcoming conference Authorship and Appropriation (University of Dundee – 8 and 9 April 2016). We hope to see many of you there, and will say more about our papers in future blog posts!

Simply desire to say your article is as astounding. The clarity in your post is simply great

and i can assume you are an expert on this subject.

Fine with your permission let me to grab your feed to keep up to date with forthcoming post.

Thanks a million and please carry on the gratifying work.