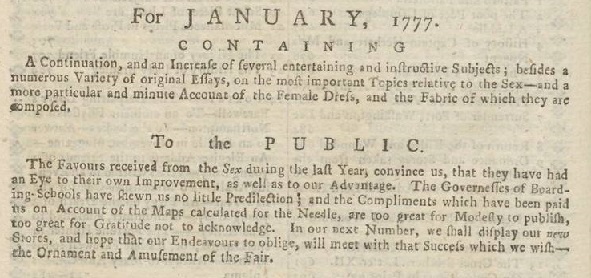

LM, XXXII (1801). Image © Adam Matthew Digital / Birmingham Central Library. Not to be reproduced without permission.

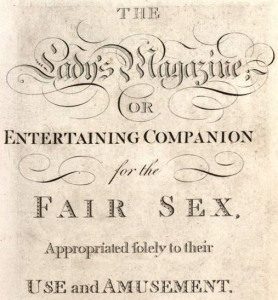

Titles are an important element of a publication’s marketing strategy, and will usually be chosen to draw the attention of a target readership. In the case of the Lady’s Magazine (1770-1837), it is quite likely that the title was meant to position this periodical as an alternative to the long-established Gentleman’s Magazine (1731-1922), suggesting that it offered content of the same standards and prestige as the male-gendered original, but more directly appealing to a female audience. As we have discussed before, it would however be a mistake to assume that the Lady’s Magazine was only read by women. Many of the reader-contributors who submitted unsolicited copy to the magazine were male, and after studying the subscription lists of provincial booksellers, Jan Fergus has furthermore found that men as well as women associated with schools for both boys and girls, and their respective pupils, constituted a significant part of the subscribers.[1] Submissions by these pupils, in a variety of genres, regularly make their appearance in the magazine.

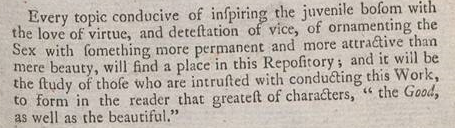

There are several reasons why the Lady’s Magazine would have been deemed suitable reading for younger readers, but we need look no further than the neat summary of the periodical’s mission in its subtitle. This tells us that the magazine is conceived as ‘an Entertaining Companion for the Fair Sex, Appropriated solely to their Use and Amusement’. Even though the many contributors do (cautiously) discuss the issues of the day, editorial notices in the magazine do indicate that submissions were turned down if they were considered potentially offensive, because they would be of a scurrilous or too controversial nature. For the standards of what would be ‘appropriate[d]’, the magazine tends not to distinguish the sensibilities of (adult) women from those of younger readers, as perhaps is typical of the age. For instance, yoking together ‘juvenile’ readers and ‘the [Fair] Sex’, the ‘Preface’ to Vol. IV (1773) aims to dispel all possible misgivings of concerned parents and professional pedagogues by ensuring that

LM, IV (1773). Image © Adam Matthew Digital / Birmingham Central Library. Not to be reproduced without permission.

The ‘Use’ mentioned in the subtitle is covered here too, by referring to the prominent educational mission of the magazine. As is often emphasized in the magazine’s internal advertisements, readers could expect more than just light entertainment from the Lady’s Magazine. They would learn from its fiction and essays rules of conduct, and from the many historical or geographical pieces they would get a smattering of book smarts into the bargain. It is clear from the above statement that the editors grasped that the “appropriated” and edifying content could potentially attract a broader readership than only adult women, foremost including younger readers. Many contributions are aimed directly at this demographic, with short fiction about young ladies often set in schools, and essays (usually in the form of letters) that tell daughters or sisters how they should behave there.

From the first year of the Lady’s Magazine onwards, we also find pieces that are attributed to such ‘juvenile’ reader-contributors themselves. Like most of the contributions to the magazine, these are mostly anonymous or pseudonymous, but with precocious young authors the age is sometimes stated, and affiliations with specific schools are often emphasized. No doubt this was an opportunity for the represented schools to advertise the level of their pupils. Especially in its early years, the magazine often included short French essays with the invitation to submit translations for inclusion in the next number, and for instance in 1775 one such translation, suspiciously faultless, appeared from a “G. Stennett, aged ten years, at the Academy, Woodford, Essex” (Vol. VI, p. 180). Perhaps it was common for Miss or Sir to have a quick look at the efforts of their wards before they were sent off. The merits of boarding schools for girls are a topic of debate among correspondents in the magazine’s earlier years, and for those institutions it must have been a concern that they appeared at their best. Additionally, it is possible that the magazine was used as material for classroom assignments. Though some translators can be identified as adults, these translation exercises do noticeably often appear with full mentions of the school or age of teenage contributors. The submission of the class’s best work to the Lady’s Magazine may have been an appealing incentive to ambitious pupils. Translations of short Latin poems and excerpts from the Classics sometimes appear too, and may well have originated as (a boy’s) classwork. After the first decade these possibly didactic items become rarer.

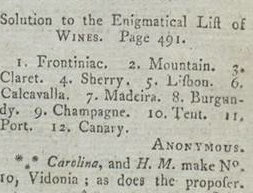

The flow of items in other genres, however, continues unabated. During the entire run of the magazine, ‘enigmatical lists’ are often supplied by girls at boarding schools, who clearly enjoyed writing fanciful descriptions of each other. There is no practical advantage to circulating a riddle throughout the British dominions that could hardly be solved by anyone not living in the same house as you, but let s/he who never chats to colleagues on Facebook cast the first stone. There would of course be the joy of seeing one’s submission in print, which was no doubt an even greater thrill to the many young contributors regularly sending in poems, usually short and lyrical.

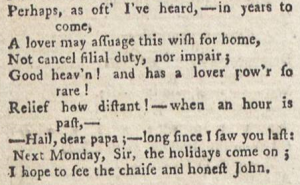

LM, I (April 1771), p. 431. Image © Adam Matthew Digital / Birmingham Central Library. Not to be reproduced without permission.

Poets will draw inspiration from their surroundings and experiences, and these aspiring bards are no exception. Already in 1771 ‘a female genius at a boarding school in Leicester’ (Vol. I, p. 431) apostrophizes her ‘dear papa’ in a poem about her homesickness. How many now legendary poets started off by writing verse like this?

Dr. Koenraad Claes

School of English, University of Kent

[1] Fergus, Jan. Provincial Readers in Eighteenth-Century England. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2006. passim