Magazines have not, as a rule, fared well in literary history. Condemned by the very topicality that once made them so popular, periodicals are often cast as the mere ephemera in the face of which works of true literary merit have endured.

The bad press that magazines have received is not unwarranted. The eighteenth-century periodical marketplace could be as cut-throat and unprofessional as it was lively, with some titles barely lasting for a handful of issues. Even those serial publications that enjoyed much longer print runs bear material witness to their contingent status. Few survive intact. Readers routinely removed plates and engravings. They frequently ripped out embroidery patterns or song sheets and wrote copiously in the margins or scribbled all over their pages.

LM, XXXII (1801). Image © Adam Matthew Digital / Britishl Library. Not to be reproduced without permission.

Yet, the blanket association of the genre with ephemera is profoundly misleading. Titles such as The Lady’s Magazine didn’t only survive by being lucky. Monthly issues were printed with an expectation that subscribers would bind them according to the publisher’s printed instructions and preserve them in bound volume form for posterity. References were made to articles in earlier volumes in expectation that readers would still have them to hand. And there is anecdotal evidence that some magazine readers went to great lengths to preserve their libraries against the ravages of the elements and time, such as the brine soaked, shipwrecked and salvaged copies of The Lady’s Magazine that Charlotte Bronte recalled reading as a child when she should have been paying attention to her lessons and which had once belonged to her mother or aunt (Letter to Hartley Coleridge 10 December 1840).

But the Lady’s Magazine was about preservation in other ways, too. From its opening issue in August 1770, the editors proclaimed that ‘Every branch of literature’ would ‘be ransacked to please and instruct’ (LM 1 (August 1770): 1). No generic stone would be left unturned in their pursuit to cultivate the female mind; nor would the work of any living or dead writer (man or woman) whose literary efforts conduced to female improvement.

Although a good deal of the content of the magazine was apparently original, much besides was repurposed from extant sources. Indeed, one of the many strands of our research project is divining the shifting ratio of old to new content over the course of the magazine’s run. I must confess, however, that when I first began reading the Lady’s Magazine more than fifteen years ago, I tended to skip those poems and extracts from those books on travel, history, religion and conduct I could read elsewhere. I noted with little more than passing interest that the magazine was fairly even handed in its inclusion of nuggets of wisdom from uncomfortable bedfellows such as James Fordyce, Dr Gregory and Mary Wollstonecraft.

The more I read the magazine, however, the more I became interested in what works and which authors the magazine chose to acknowledge and how. Why reprint that particular letter of Lady Mary Wortley Montagu’s (on hair dye) in August 1771 (II: 68) and not another? Why those particular extracts (‘On Modesty’ and ‘The Character of the Notable Woman and Fine Lady Contrasted’) from A Vindication of Woman in the June 1792 issue of the magazine?

These are not always easy questions to answer. Neither are the effects of these selections – whether made by editors or by enthusiastic readers who transcribed passages of their own choosing – always easy to fathom. But two things are clear: such choices matter; and sometimes they surprise.

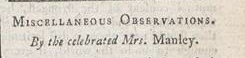

LM, XII (1781): 135. Image © Adam Matthew Digital / Birmingham Central Library. Not to be reproduced without permission.

No one would be shocked to find Montagu or Wollstonecraft occupying page space in the 1770s and 1790s of the magazine, or by the numerous laudatory references to the Bluestockings throughout the first decades of the title’s run. Some might be slightly taken off guard, however, by the extracts from The New Atalantis (1709) that appeared in the March 1781 issue under the title ‘Observations by the celebrated Mrs. Manley’ just four years before another (albeit reluctant) Lady’s Magazine contributor, Clara Reeve, remarked that Manley’s works were best forgotten in The Progress of Romance. Few readers could similarly have expected that the poet Elizabeth Thomas, known popularly in literary history as ‘Curl’s Corinna’ thanks to Alexander Pope, would form the second subject of the magazine’s ‘Lady’s Biography. Modern’ series in May 1771.

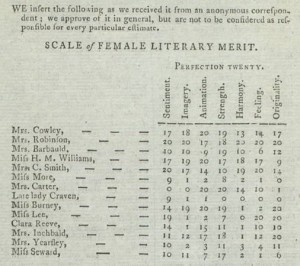

One of the many important aspects of the Lady’s Magazine that our project index will help to shed light on is who the magazine was keen to preserve for literary posterity and who it was not in the form of its long-running biographical series of illustrious literary women and selections from the works of noted writers. Such data has the potential both to underscore and (perhaps more importantly) to disrupt some of our entrenched assumptions about the making of literary history in the second half of the long eighteenth century.

This was a project that, as we know, had serious repercussions for the status of women writers and women’s writing, even if the magazine itself could sometimes be rather less than serious about the important work of preservation and the rather specious criteria upon which such acts of literary judgement were made.

LM, XIII (June 1792). Image © Adam Matthew Digital / Birmingham Central Library. Not to be reproduced without permission.

Dr Jennie Batchelor

School of English, University of Kent