Although one of the most prominent goals of our research project is to demonstrate the lasting relevance of periodicals like the Lady’s Magazine, the very ‘periodicity’ of the genre obviously required that the magazine also directly appealed to the concerns and interests of its readership at the time of each issue’s appearance. This creates the need for reference to topical events, and for the inclusion of seasonal items on important dates that are marked annually on the calendar. The most commercially successful publications have always been those that found ways in which to insinuate themselves into the day-to-day routines of their readers, anticipating what they will be thinking of when the magazine appears, and ideally even associating themselves in the reader’s mind with popular holidays or other collectively experienced recurrent events. The Lady’s Magazine would for instance dutifully print the productions of the poet laureate on the birthday of the monarch, but a more extensively covered, and maybe more appealing subject, was Christmas.

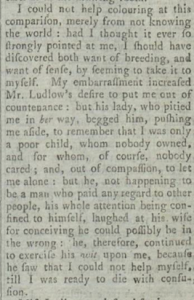

LM, VI (1775). Image © Adam Matthew Digital / British Library. Not to be reproduced without permission.

It is common knowledge that Christmas has not been celebrated in Britain in the same way throughout history, and that, besides worldly fashions, often tumultuous changes in religious regulations (and sometimes legislations) have played their role. Christmas as we know it today was after all only firmly established over the course of the nineteenth century. Nevertheless, the official commemoration of the day that, in the words of pseudonymous poet ‘Christiania’ (1775), ‘sacred deity from heaven came’, could never go by unnoticed. With its wide readership that furthermore diligently helped to furnish content, the Lady’s Magazine is a useful source on the celebration of this holiday from the late eighteenth to the early nineteenth century.

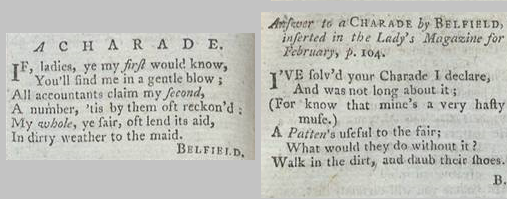

Most of the numerous and diverse Christmas-themed contributions to the magazine can be found in the annual ‘supplement’, a thirteenth issue that unlike the famous ‘Christmas numbers’ of the Victorian age shows little thematic coherence, and appears to be mainly intended to cash in on the fact that at this time of the year the public would be in a spending mood. Besides religious poetry there is also more worldly verse, as when in 1789 an anonymous poet looks back fondly ‘on five ladies who composed verses for their amusement at Christmas’. With a hyperbole characteristic of much of the Lady’s Magazine amateur poems, these “five graces” are said to be so talented at “verse divine” that the god Apollo decides to claim them for his new Muses. In her advice column, the magazine’s agony aunt and conduct guru ‘the Matron’ annually discusses her plans for the holidays, which she usually spends with her son, a country squire who provides his servants with well-supervised Christmas entertainment. Various essays that compare contemporaneous to historical customs are featured, such as on ‘Christmas sports’ (1796), and in 1780 the anonymous author of ‘Thoughts on Christmas-tide’ delivers an account of the festival across the different social strata that should be of interest to cultural historians.

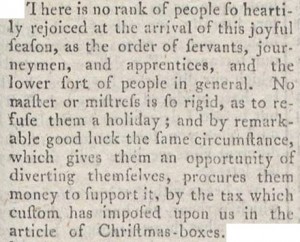

This author assures us that by 1780 only ‘old-fashioned mortals […] look upon this season with extraordinary devotion’, while ‘with the generality Christmas is looked upon as a festival in the most literal sense, and held sacred by good eating and drinking’. Housewives busily prepare ‘mince-pies without meat’, and lament that this ‘solid, substantial Protestant’ treat now shares the sideboard with ‘Roman Catholic aumlets, and the light, puffy, heterodox pets de religieuses’. Whereas in former times lords would make merry with their tenants, in the late eighteenth century ‘the servants swill the Christmas ale by themselves in the hall, while the squire gets drunk with his brother fox–hunters in the smoking room’. For common people with access to more fortunate patrons this is however still a period of relative joy:

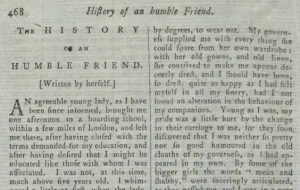

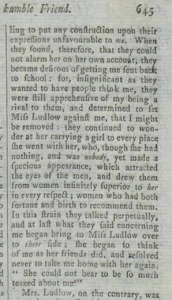

LM, XI (1780). Image © Adam Matthew Digital / British Library. Not to be reproduced without permission.

According to the author, this ‘pocket-money’ is spent on playing ‘the fine gentlemen of the week’, or as long as these limited funds may last. ‘A merry Christmas has ruined many a promising young fellow, who has been flush of money at the beginning of the week, but before the end of it has committed a robbery on the till for more’. For ‘persons of fashion’, this ‘annual carnival’ is of course most horrible: ‘boisterous merriment, and aukward affectation of politeness among the vulgar, interrupts the course of their refined pleasures, and drives them out of town.’ As the author (ironically?) concludes, ‘[t]hese unhappy sufferers are really to be pitied’.

Locating within the Lady’s Magazine material on Christmas, or any other topic, will become very easy in early 2015, when we launch our annotated index. In the meantime the team wishes you a merry Christmas and a happy New Year.

Dr. Koenraad Claes