With the University year now over, it’s back into the planning period, developing ideas for repertoire and programming for next year.

One of the projects I’m currently devising for the University Cecilian Choir is a performance – well, perhaps ‘realisation’ is a more appropriate term – of David Lang’s Memorial Ground, co-commissioned by East Neuk Festival and the 14-18 NOW: WW1 Centenary Art Commissions, to commemorate the Battle of the Somme.

One of the projects I’m currently devising for the University Cecilian Choir is a performance – well, perhaps ‘realisation’ is a more appropriate term – of David Lang’s Memorial Ground, co-commissioned by East Neuk Festival and the 14-18 NOW: WW1 Centenary Art Commissions, to commemorate the Battle of the Somme.

What’s fascinating to me about the piece is the multitudinous ways in which it can be realised. The piece’s great strength is its adaptability, its flexibility which allows ensembles to craft it in a way which will make it unique to their performance. The possibilities of including poetry, spoken word, wordless solos, even instruments, offers plentiful creative opportunities to put together a performance that can reflect, resonate with, or speak to different spaces, different venues, different times. Usually, as a conductor, you’re endeavouring to be as fidelious to the score as possible, paying close attention to realise the piece in a way faithful to the composer’s intentions. With this piece, however, you are given freedom to realise the piece in any manner you wish, using content supplied by the composer but also with the ability to involve additional material beyond that supplied by Lang. Of course, there’s a responsibility to make sure that new material is appropriate to the nature of the piece’s artistic intent, that it fits thematically, emotionally, such that the piece can accommodate it, without the new ideas feeling deliberately grafted or imposed onto the pre-composed material.

Once the new academic year begins in September, the Cecilian Choir will form at the beginning of October, which will give us approximately four rehearsals to put the piece together, and I’m hoping to be able to perform the piece several times during November, the month of Remembrance, in contrasting venues – one of which might be the bomb-crater on the hillside north of the city, on the University campus. The crater dates from the Baedeker Raids between 31 May – 7 June during World War Two, rather than from the First World War, but it remains as tangible evidence of the countryside scarred by armed conflict. A performance of the piece, with the Choir at the bottom of the crater and audience arranged around the slopes, might be particularly effective, as the piece speaks across the years to a site directly connected with the country at war.

It’s particularly exciting to be preparing the piece to start rehearsals in October, searching for suitable materials to use as text, including poems, and songs from the period, to imagine different ways in which to bring the piece off the page, and to consider suitable venues in which to bring it to life. It would be a fitting way of commemorating the events of the Battle of the Somme, and all those who gave their lives – both then and ever since – in war.

We’ll keep you posted as to how the project unfolds.

As the sun set, the ancient site rang to the sound of medieval plainchant as the performance opened with a Kyrie by Hildegard von Bingen, the long lines lifting and skirling around the keep and lifting into the blue skies.

As the sun set, the ancient site rang to the sound of medieval plainchant as the performance opened with a Kyrie by Hildegard von Bingen, the long lines lifting and skirling around the keep and lifting into the blue skies. As the programme unfolded, you could feel the audience draw closer to the music across the shingle area which separated the singers from the boarded walkway, around which the audience stood or sat. Assistant conductor Joe Prescott drew forth a tight-knit Ave Verum by Mozart and and sprightly O Swallow, Swallow by Holst, amongst other works.

As the programme unfolded, you could feel the audience draw closer to the music across the shingle area which separated the singers from the boarded walkway, around which the audience stood or sat. Assistant conductor Joe Prescott drew forth a tight-knit Ave Verum by Mozart and and sprightly O Swallow, Swallow by Holst, amongst other works.

The performance came to a dramatic conclusion with a militant Norwegian setting of the Song of Roland, with drummer Cory Adams positioned above the audience in one of the castle towers, stridently beating a decorative accompaniment that recalled the military nature of the castle’s history in vivid, echoing sound.

The performance came to a dramatic conclusion with a militant Norwegian setting of the Song of Roland, with drummer Cory Adams positioned above the audience in one of the castle towers, stridently beating a decorative accompaniment that recalled the military nature of the castle’s history in vivid, echoing sound.

The weekly programme celebrating choral singing will feature the Choir as part of its ‘Meet My Choir’ slot, in which it highlights choirs from around the country. Needless to say, the student and staff members of the Cecilian Choir are very excited at the prospect.

The weekly programme celebrating choral singing will feature the Choir as part of its ‘Meet My Choir’ slot, in which it highlights choirs from around the country. Needless to say, the student and staff members of the Cecilian Choir are very excited at the prospect.

Last night was spent, therefore, making the piece sound as vital, as alive and challenging as possible. From the brilliant opening cry of the chorus, through the pastoral intimacy of the central Domine Deus to the fervent finale, we built a revitalised reading of Vivaldi’s masterpiece, which we will unleash in the Crypt this coming Friday. Combined with the exploratory first half – choral pieces across the centuries, from Hildegard von Bingen to Veljo Tormis – the concert promises to be something quite special.

Last night was spent, therefore, making the piece sound as vital, as alive and challenging as possible. From the brilliant opening cry of the chorus, through the pastoral intimacy of the central Domine Deus to the fervent finale, we built a revitalised reading of Vivaldi’s masterpiece, which we will unleash in the Crypt this coming Friday. Combined with the exploratory first half – choral pieces across the centuries, from Hildegard von Bingen to Veljo Tormis – the concert promises to be something quite special.

And all the weeks of nagging – by both myself and this year’s assistant conductor, Joe – finally began to yield results last night. The ensemble sound was more confident, the choir was beginning to find its feet and start to perform, rather than simply singing through the repertoire.

And all the weeks of nagging – by both myself and this year’s assistant conductor, Joe – finally began to yield results last night. The ensemble sound was more confident, the choir was beginning to find its feet and start to perform, rather than simply singing through the repertoire. The other aspect to last night’s rehearsal was a first try-out of the choir’s concert outfits, to see if the colour and co-ordinating will work. This year, we’ve gone for the simple but stark contrast of black and cream, and last night we sang for most of the session in concert-dress; and it does make a difference. Not only do you need to sound like a choir, you need to feel like one; to stand and deliver in a manner that tells the audience that you know what you are doing, and that wins the listener’s trust even before you have sung a note. Standing like a choir last night also helped them sing like one too.

The other aspect to last night’s rehearsal was a first try-out of the choir’s concert outfits, to see if the colour and co-ordinating will work. This year, we’ve gone for the simple but stark contrast of black and cream, and last night we sang for most of the session in concert-dress; and it does make a difference. Not only do you need to sound like a choir, you need to feel like one; to stand and deliver in a manner that tells the audience that you know what you are doing, and that wins the listener’s trust even before you have sung a note. Standing like a choir last night also helped them sing like one too.

This is my fifth year of working at the University, and you’d have thought that I’d have grown accustomed to this situation by now. But it doesn’t get any easier; there’s so much fun to be had amidst the hard work, and so much satisfaction accrued from delivering a polished performance, that bidding farewell to the ensembles, and the singers of whom they are comprised, is difficult. There will, of course, be new faces next year, new singers and new members as the Choirs re-form and begin anew their musical exploration together – always an exciting start to the academic year. But I will miss the incarnation of each Choir; it’s been a large part of my working year, in which my expectations for them have been matched by their whole-hearted commitment.

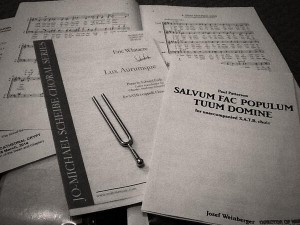

This is my fifth year of working at the University, and you’d have thought that I’d have grown accustomed to this situation by now. But it doesn’t get any easier; there’s so much fun to be had amidst the hard work, and so much satisfaction accrued from delivering a polished performance, that bidding farewell to the ensembles, and the singers of whom they are comprised, is difficult. There will, of course, be new faces next year, new singers and new members as the Choirs re-form and begin anew their musical exploration together – always an exciting start to the academic year. But I will miss the incarnation of each Choir; it’s been a large part of my working year, in which my expectations for them have been matched by their whole-hearted commitment. This morning’s critical pre-performance tasks have already been achieved: see offspring off to school, iron concert-shirt, polish shoes, leap around on Twitter to promote tonight’s concert; now I can sit with the music and work through the scores, until heading towards the crypt for this afternoon’s rehearsal. The first moment we sing in the Crypt on the Friday afternoon is always a memorable moment, particularly for those members of the Choir who haven’t sung there before; the rich, sonorous acoustics take your sound and echo it around for several seconds. We’re very excited at the prospect of launching the opening of Eric Whitacre’s Lux Aurumque into that historic space.

This morning’s critical pre-performance tasks have already been achieved: see offspring off to school, iron concert-shirt, polish shoes, leap around on Twitter to promote tonight’s concert; now I can sit with the music and work through the scores, until heading towards the crypt for this afternoon’s rehearsal. The first moment we sing in the Crypt on the Friday afternoon is always a memorable moment, particularly for those members of the Choir who haven’t sung there before; the rich, sonorous acoustics take your sound and echo it around for several seconds. We’re very excited at the prospect of launching the opening of Eric Whitacre’s Lux Aurumque into that historic space.