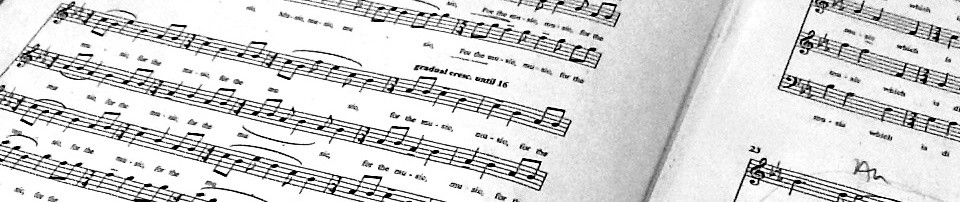

The Cecilian Choir reached the French stage of their concert programme this week, with motets by Duruflé and Poulenc. Duruflé’s achingly beautiful Ubi Caritas et Amor is part of a set of four motets using Gregorian themes, clothing pieces of plainchant with wonderfully rich colours.

As part of the programme, we will be singing the piece of plainchant itself separately, followed by the motet; the intention is to telescope the medieval and modern, juxtaposing the ancient modal chant with the modern exoticism of Duruflé’s setting. We began the rehearsal with the plainchant, learning to follow the natural rise and fall of the phrases and leave a measure of flexibility in singing through the lines.

Duruflé gives the plainchant melody to the altos at the start of Ubi Caritas, so the alto section were grateful for having learnt their line already when we came to learn the motet. There are some lovely cluster-chords in the piece; the plainsong grounds the tonality firmly in Eb, whilst the accompanying sonorities clothe it with all manner of jazz-indebted, added-note harmonies. We were short of several people this afternoon – the Housing Fair had students flocking to it in order to organise their accommodation for next year – but the choir still managed to bring out most of the colour. The tenors and basses were underpowered, though: talking to some of the group afterwards, most of the sopranos had already arranged their accommodation: are women more organised and efficient than men, perchance ?!

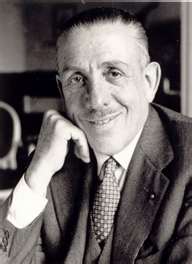

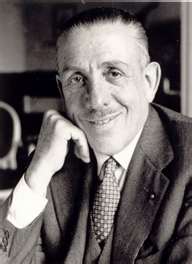

Using my trick of learning new pieces backwards that I’ve talked about before, we started halfway through Poulenc’s Exultate Deo, which we’d briefly started last term. It’s jolly hard: Poulenc’s trick of swinging through adjacent or parallel harmonies that are not necessarily related to each other makes for some angular lines in the voices; quite often, the altos and sopranos are having to leap over augmented fourths or fifths, and the score includes a fistful of double-sharps or enharmonic changes that mean what appears to be two different notes are actually the same one. We learned a section carefully, practicing moving between difficult chords to make sure the voices knew where they were going.

Using my trick of learning new pieces backwards that I’ve talked about before, we started halfway through Poulenc’s Exultate Deo, which we’d briefly started last term. It’s jolly hard: Poulenc’s trick of swinging through adjacent or parallel harmonies that are not necessarily related to each other makes for some angular lines in the voices; quite often, the altos and sopranos are having to leap over augmented fourths or fifths, and the score includes a fistful of double-sharps or enharmonic changes that mean what appears to be two different notes are actually the same one. We learned a section carefully, practicing moving between difficult chords to make sure the voices knew where they were going.

With a great deal of slow note-bashing and difficult lines to sing, one could sense morale dropping slightly; working backwards in two-page sections made life somewhat easier, as we covered passages more familiar from last term. Recapping previously-sung sections and singing into and through the new passages meant the piece gradually began to come together: there was definitely a sense of ‘Ah, I recognise this bit from last term!’ followed by ‘Ah, now I’m starting to recognise the new bit as well!’ which meant dipping spirits began to rally.

We ended by singing through Ubi Caritas once more, in order to reassure ourselves that we had learned something well enough at this rehearsal, and to lift morale – “We can DO this!” I’ve altered the planning of rehearsals this term – we’ll be looking at chunks of the Poulenc each week, along with the other repertoire to learn, and be working on it as more of a long-term piece. But parts of it are already starting to sound excellent, and I’m sure we’ll get there. It’s such a great piece, it will be worth it…

And just to demonstrate what we’re working towards, here’s the choir of Kings’ College, Cambridge, singing the Duruflé (with what appears to be a young David Tennant in the alto section…). The singing, like the piece, is exquisite.

(Preview extracts via LastFM).