For National Marketing Day (11 January), Emily Collins, Sustainability Champion and External Relations and Events Co-ordinator in Research and Innovation Services, shares her thoughts on why this doesn’t need to be the case.

When I was young, I always thought that marketing was about selling people too much of what they don’t want or need. Even now, having started a Marketing Manager apprenticeship with Cambridge Marketing College, my inner morality compass has been squirming at the conflict between this traditional view of marketing and my desire to live more sustainably.

Over time, however, I’ve come to realise that good marketing should, as defined by my College, ‘identify and satisfy customer needs and building systems around this principle’. With 65% of consumers wanting to buy purpose-driven brands that advocate sustainability (Harvard Business Review, 2019), a customer-focussed approach creates opportunities for companies to boost sustainable activity, both in terms of how they deliver services and products to customers, and influence people’s purchasing behaviour.

Take smol, for example, a business which provides ‘planet-friendly’ cleaning products. I’d never even considered switching from traditional laundry tablets until ads popped up on Facebook offering me a free trial of their plastic-free version. Tell me, who doesn’t need laundry tablets? So I ordered a pack and two years later, I’m still receiving them in the post every month, content that I’m not polluting the planet nor likely to run out of laundry tablets again.

smol’s success hasn’t gone unnoticed; Ariel have recently followed suit by developing their own sustainable ECOCLIC box. I think it’s safe to assume that Ariel’s marketing teams will be carefully analysing how many people purchase this product. If successful, it will give them fuel to influence internal decision-making in favour of widening their sustainable packaging range – putting the power with the consumer!

Despite sustainable products becoming more widespread in response to customer and legislative demands, you only need to look around to realise that they aren’t always at the top of our to-buy list. In fact, whilst 65% of consumers want to buy purpose-driven brands that advocate sustainability, just 26% of consumers actually do (Harvard Business Review, 2019). The reasons for this are numerous, but by gathering and analysing data on customer behaviour, marketers can better understand this ‘intention-action gap’ and identify the most effective ways to close it.

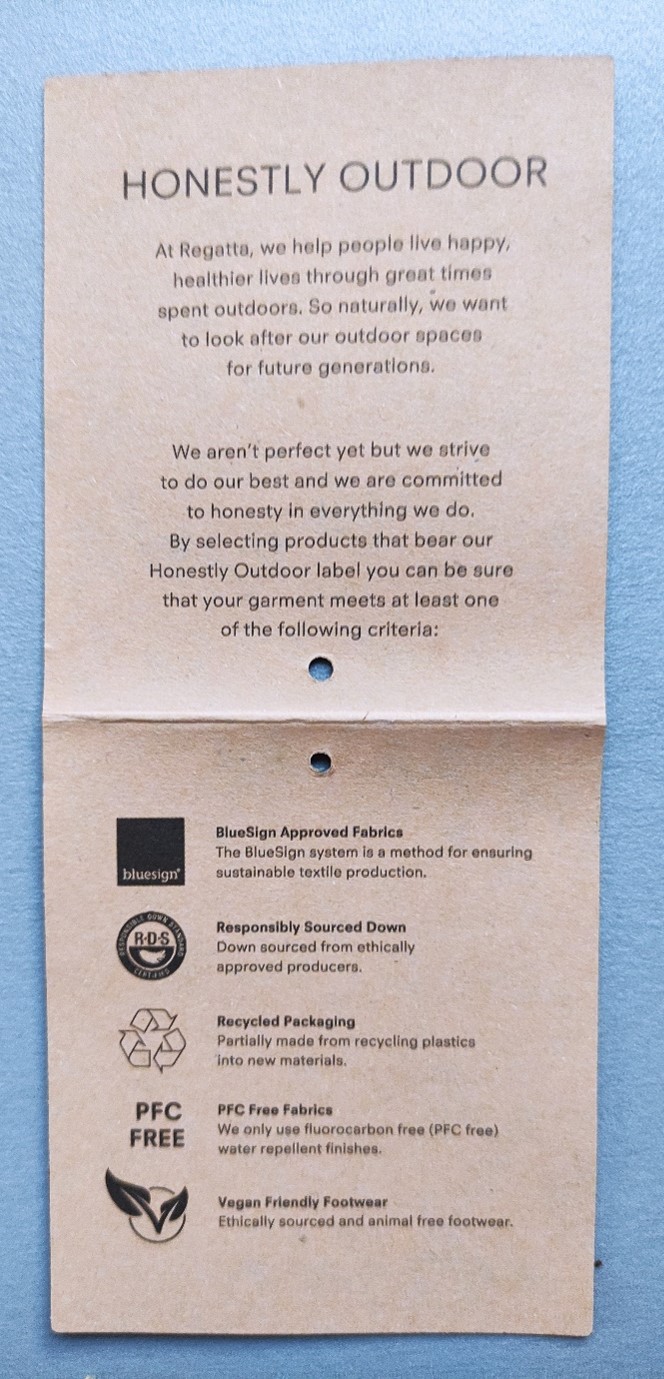

Of course, this needs to be achieved without falling into the ‘greenwashing’ trap – i.e. making people believe your company is doing more to protect the environment than it actually is. In 2021, the European Commission published a report suggesting that 42% of green online claims are exaggerated, false or deceptive. Large and small companies have fallen foul of this trend in the hopes of capturing the interest of eco-conscious consumers with their marketing campaigns – only to be called out and lose customer loyalty and trust in the process.

One reason organisations can get away with this is a lack of climate literacy globally. In a study of German, French, Italian, UK, and U.S citizens, only 14.2% of respondents proved to be truly climate literate. Yet it’s been shown that 94% of consumers are more likely to be loyal to a brand that’s completely transparent, so it is in marketers’ interests to use their position of influence to educate consumers (and internal staff) on the right terminology so that consumers can understand the evidence and credentials for themselves. That is, of course, if their sustainability strategy is anything to shout about!

Marketing also provides an opportunity for companies to change our traditional view of consumption. We’re already seeing examples of this, from the Vinted ad campaigns for sustainable fashion app, to Octopus Energy’s Saving Sessions, which reward customers for using less power. The same data, creativity and tools used by marketers to drive consumption could prove vital to changing customer and shareholder perceptions of value and help us on our way to adopting a circular economy.

If you’d like to learn more about marketing and how it is being used to inform and drive sustainable action, I recommend you listen to the “Can Marketing Save the Planet?” podcast, founded by Michelle Carvill and Gemma Butler, which hosts guests from a range of industries to discuss the successes, opportunities and challenges faced by the marketing industry. It provides an insight into an industry which is still learning how to be good – and in which I believe being good at your job shouldn’t always mean encouraging people to consume more.