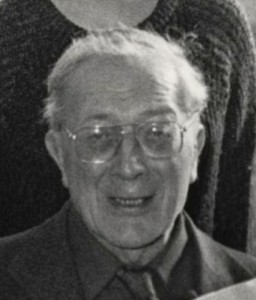

I thought I would share with you another find which came out of the Baldwin archive last week. It was a chance find; I spotted it as I was flicking through one of the many black folders to list the types of materials enclosed. Having said that, I think it’s one of the most important, since most of us working on this collection had no idea what the collection’s tireless collater actually looked like. So, here he is: Mr Ronald Baldwin.

Mr Baldwin was a keen local historian and produced The Gillingham Chronicles : a history of Gillingham, Kent as well as teaching on the subject. He was also a keen collector of ephemera, a Bible Christian (a sect which sprang out of Methodism) and his interests ranged across many disciplines from brickmaking to elections, and trains to trade tokens. In starting the work on the remaining uncatalogued material in the Baldwin collection, we have only begun to get a sense of the sheer scope of his interests.

What was really nice about finding this photograph was to finally put some kind of identity to the collection. The sheer range of collections which we hold makes it difficult to keep track of the individuals who dedicated significant time, often a lifetime, to their collecting. Some, for example the Melville family or Hewlett Johnson, were larger than life and more than a trace of their exceptional personalities has come across in the work which they have left us. Others, like Jack Johns, Jack Reading and Colin Rayner, are almost anonymous in their own collections now that the majority of the staff who knew them have moved on. Of course, those collections are the ones which were collected for their own sake, rather than about a particular individual. It’s interesting to reflect, when it comes to our work with archives, about the reasons behind its creation and the uses to which the collator wanted their collection to be put.

Once the collection is passed to any institution, of course, the needs and abilities of that institution play a role in the archive’s evolution and uses. UoK’s Special Collections is no different to other museums and archives in this; when we accept collections, we do so on the understanding that the materials will be used in order to make an important contribution to the learning and teaching at the University, and will benefit the wider community. In this way, I think that Mr Baldwin’s collection may be one of the most difficult to ‘pigeonhole’: his collection is so varied that I hope the materials will, when available, be of use to many people both inside and outside the University.

So, the work we’re currently carrying out on Mr Baldwin’s collection is focussed on the materials which weren’t put straight into Special Collections’ Local History section. This section consists of around 800 ringbinders full of notes, cuttings, photographs and ephemera, over 4000 published volumes and some postcard albums. There are also some more indentures and legal documents, later than those which caused a lot of excitement when they were discovered to date from 1424 up to the reign of Charles II. The current process is to pull the ringbinders out of their (slightly disordered) storage space in order to try to recreate Mr Baldwin’s sequence. Due to constraints on time and space, we’re pulling out small groups of folders on related disciplines, boxing them up and listing them. Once our lists are complete, we’ll be able to pull together the themes and subjects to create manageable sections to continue our work. It’s only a preliminary stage and it will probably be some time before work on the archive is completed, but the sheer amount of information which Mr Baldwin collated means that this will be a worthwhile task.

So while we see countless photographs of countless people in our day to day lives, it’s nice to have Mr Baldwin looking on over ‘Baldwin Corner’ as it fills up with organised boxes containing just a fraction of his life’s impressive collection.