Yesterday was the annual Centre for the History of the Sciences (CHOTS) Away Day. Last year’s visit was to Chatham Dockyard: this year, although there were some maritime connections and we continue to make the most of Kent’s heritage, we were considerably more domestic at Down House.

Down House is, as the English Heritage website tells us, the “Home of Charles Darwin”. Like the Charles Dickens Museum or Pasteur Museum, it is in essence an attempt to convince us that the genius has just left the room: letters and pens are on the desk, coats hang in the hallway, and the family might just let us stay for a cup of tea. These men, famous in their lifetimes, were being memorialised even before they had kicked buckets and shuffled off coils – their families and colleagues kept not just their writings but also their handkerchiefs and desks, making full-blown recreations a possibility.

Down House was, however, not quite ready to open as a memorial and museum by the time of Darwin’s death in 1882, or even that of his wife Emma in 1896. The family let the house for a period, and for twenty years in the early 20th century it was a girls’ school. The second of the two schools closed in 1927, at which point an appeal was made by the president of the British Association for the Advancement of Science to save it for the nation. The benefactor who stepped up was the surgeon Sir George Buckston Browne and the house was opened as a museum in 1929, since when it has been overseen by the BAAS, the Royal College of Surgeons (1953-1996) and now English Heritage (with financial assistance from the Wellcome Trust, Natural History Museum and Heritage Lottery Fund).

Although we heard briefly about the later history from our guide, it does not feature in the displays, and neither do any of the pre-1840s owners of this Georgian villa. It is, unsurprisingly, all about Darwin, with recreations of the famous study, the sitting room, billiards room and rather splendid dining room downstairs, and attractive displays about the history of natural history, the voyage of the Beagle, Darwin’s work and family upstairs. The period rooms are, we were assured, full of genuine items from Darwin’s time, although props certainly featured and we were left unsure about whether or how much of the library was Darwin’s. The rooms have been recreated with the help of photographs taken by Darwin’s son Leonard.

Upstairs was equally full of treasures, this time in more conventional museum case displays, with the notebooks, the finches and Annie’s box featuring alongside other items from Darwin’s time on the Beagle and at Down. There were also galleries aimed at schools and children which amused us and, I’m sure, any children who visit.

For us, however, it was the gardens that were the main feature of the visit, partly because they are lovely and very evocative of Darwin’s passions, but also because we were treated to a knowledgeable tour by Down’s head gardener, Rowan Blaik. He was more than capable of giving this bunch of historians of science chapter and verse on the many experiments that Darwin conducted within the garden, and which had been used and how within Origin of Species, as well as helping us see how the family used the gardens (Emma ordered flowering plants haphazardly from catalogues; the children used the “ancient mulberry” tree to climb down from the first floor; the family set up one of the earliest hard tennis courts late in the century; and everyone stepped in and out of house and garden through the low dining room windows).

We saw a recreation of the “seedling mortality experiment”, through which Darwin showed that only 1 in 8 of the seedlings that germinate reach an age at which they can reproduce: competition, struggle and death within a few square inches of English countryside. There were also the climbing plants (which Darwin categorised), the primulas (that he showed did not speciate within a generation), the carnivorous plants and orchids on which he published, the worm stone and bees, all ready to be tested for their route-following and comb-building instincts.

Also, of course, there is the Sandwalk, on which Darwin strolled twice daily – you too can see if it works as your “thinking path”.

The planting in the gardens is meticulously managed, recreating what we know of Darwin’s world. The plants that have survived since his time are carefully maintained or, if they’re no longer viable, cloned and regrown. If he received plants, as he often did, from Joseph Hooker at Kew Gardens, then clones of surviving plants there – collected at the same time – can be grown. The surrounding fields are places in which the diversity of the flora has been studied longer than anywhere else on earth.

There has been an attempt to make Down and its surroundings a World Heritage Site (this decision was deferred in 2010, and it awaits renomination). It is a fascinating and unusual case as heritage, based not on outstanding architecture or a particular national cultural tradition, but on this long history of a relationship between scientific ideas, a particular geographical location, national heritage and celebrity. As Charlotte said (on the Sandwalk, of course), the extent to which the plants have been given agency in this context is particularly intriguing. So too is the overriding focus on the preservation of individual plants, species and a particular historical moment, given the context of waste, death and change that is natural selection.

As a day out, whether or not you are a Darwin fan, it is highly recommended – close London, as Darwin always wished, and yet (despite being reached by London bus and Oyster card) utterly within its village and countryside. A tea room beckons or, for later, Bromley’s CAMRA pub of 2014 is handy in Downe village. And, above all, the place retains a fascination, even for a cynical bunch of historians.

- Down House’s head gardener introduces the house and gardens to CHOTSers

- Head Gardener, Rowan Blaik, explains the seed mortality experiment recreation.

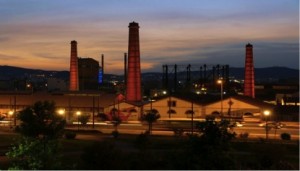

- Landscaping was carried out when the Darwins arrived: earth removed at the front to lower the road (for privacy) and brought to rear to create mounds.

- The rear of the house, showing climbing plants, dining room and (far right) mulberry tree.

- The kitchen garden with primulas nearest and the hot houses containing carnivorous plants and orchids.

- The path to the Sandwalk.

- Darwin’s study (we tried to work out how the chair and footstool and wheels might have been used – probably not with the desk…).

- Hutton, Paley et al…

- Some icons: the red notebook and the finches.

Recent Comments