It’s a hot July day in Rome, a shimmering heat haze hovers above the cobblestones of the forum of Augustus. Lucius’ stomach rumbles and his throat is as dry as papyrus. It’s time to make a detour to a popina — the ancient Roman equivalent of the modern snack shop or bar!

Style and structure

For many Romans, whose cramped tenement apartments did not run to mod cons such as cooking facilities, the popina was an essential part of everyday life. Although no ancient bars survive in Rome, they litter the streets of sites such as Pompeii, Herculaneum and Ostia, giving us a good idea of what these places actually looked like. The bars are often found on street corners or busy main streets. At Pompeii, the street that runs alongside the theatre district from the Porta Stabia had no less than 13 bars, all vying for customers.

A bar at Ostia (I.2.5) with its large front-of-shop counter decorated in marble. Image: Paula Lock.

You can usually spot a bar by the wide shop front opening directly onto the street and the service counter placed at the very front of the shop — a position that allowed customers to be served on the go. To attract customers, some canny bar owners adorned their counters with elaborate designs. Decoration ranged from sophisticated marble to painted images such as mythological scenes, plants and animals, and theatre masks, all of which were intended to chime with the interests and aspirations of the would-be customer.

The counters varied in height considerably but on average were about 80 centimetres tall, somewhat lower than the counters found in modern bars. Unlike today’s establishments, the counters in Roman bars were not necessarily set up so that children could not use them — in fact, one bar at Pompeii has a mysterious ‘step’ that might have been used by children to reach the counter. We also find evidence of children close to the bars, where, just as you may have seen in the Four Sisters in Ancient Rome film, they have made their mark with graffiti — often drawing little stick men. It would seem that it might have been reasonably common to see children in a Roman bar — maybe this is one way they began to learn how to behave as an adult.

Left, the ‘Grande’ bar at Herculaneum, IV.15-16. Top right, one of the smallest bars in Pompeii, VI.16.33. Bottom right, plaster cast of the shutters that would secure the shop at night (Pompeii, IX.7.10). Images: Paula Lock.

Many of the bars had some kind of cooking facility either built into the counter or placed at the shop threshold — a position that would help to expel smoky fumes and send the aromas of cooking food wafting down the streets.

The bars came in a variety of shapes and sizes — the smaller places would have been standing room only, whereas others would have offered a more leisurely experience with tables and stools. A few of the better class establishments even had couches on which to recline.

The menu

So what might Lucius find on a bar menu to relieve his hunger pangs? The ancient literature gives us some clues — they talk of ‘cuts of meat fetched smoking hot from wayside cookshops’ (Suet. Vit. 13.3.6), tripe (Juv. 11.81), green vegetables and dried beans (Suet. Ner. 16.2.4), and ‘hot tarts’ (Plaut. Poen. 41).

More revealing still is a graffito found in a room connected to a bar at Pompeii that lists products that were either bought or sold. The list includes bread, cheese, sausage, whitebait and porridge. You can find the full list here, and the Latin text here (paste ‘CIL 04, 05380’ into the top box). If you are learning Latin you could have a go at ordering your own bar food.

Exercise: This link will take you to some authentic Roman recipes. Many of the ingredients used by the Romans will be familiar to you, but see if you can spot any that you don’t recognise — do they sound enticing?

If you fancy making some Roman bread, watch chef Giorgio Locatelli guide you through the process here.

Frescoes from the back room of the bar at VI.10.1, Pompeii. Left, customers seated around a table, note the foodstuffs hanging above their heads. Right, a customer gets a refill of Setinian wine. Images: Paula Lock.

And what would Lucius wash his food down with? Perhaps a little wine. Roman wine was much stronger than the wine we drink today, so it was diluted with either cold or warmed water (3 parts water to 1 part wine). Although children of Lucius’s age would not be served alcohol in bars today, in ancient times, wine was the main drink for everyone. However, as you may have spotted in the film, A Glimpse of Teenage Life in Ancient Rome, despite the consumption of wine being the norm, this did not stop the Secundus boys overindulging.

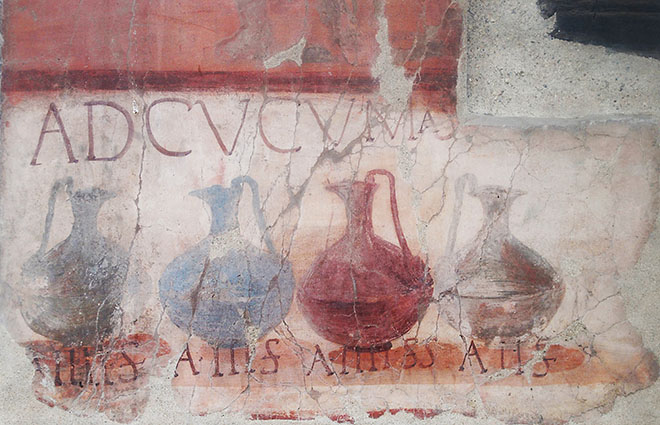

The Romans had a range of wines to choose from that varied in price according to quality. This is illustrated in a sign from Herculaneum and a graffito from Pompeii, which mentions the popular Falernian wine.

Hedone says, ‘You can drink here for one as, if you give two, you will drink better; if you give four, you will drink Falernian.’ (CIL IV 1679)

Translation from Pompeii and Herculaneum: A Sourcebook, Alison E. Cooley and M. G. L. Cooley, (p.235, H20).

A shop sign from Herculaneum, advertising the prices of different wines. Image: Paula Lock.

The wine was often seasoned with ingredient such as pepper, honey or cumin. Some people were so particular about the spices that went into their wine, that they took their own particular mix along with them when they went travelling.

A poem attributed to Virgil also mentions the types of fare on offer at a bar, whilst giving us a flavour of what the ambience might have been like. The poet talks of the sounds of music, the splash of water, the song of the cicadas and the smell of roses and fragrant fruits. You can read the poem here.

The customers

This portrayal of a bar is in stark contrast to the picture we get from most of the literary sources. This is because the upper-class Romans had a rather snooty attitude towards the bars, their patrons and to what the shops sold. For example, the bar is described as an ‘infamous and shameful vittling house’ (Lucil. 1.11), a ‘greasy café’ (Hor. Epist. 1.14.21), nasty eating house (Hor. Sat. 2.4.62), vile cookshop (Cic. Pis. 13.4) and reeking cookshop (Juv. 11.81).

Juvenal gives us a rundown of the type of characters that might typically be seen in such a place…

Send your Legate to Ostia, O Caesar, but search for him in some big cookshop! There you will find him, lying cheek-by-jowl beside a cut-throat, in the company of bargees, thieves, and runaway slaves, beside hangmen and coffin-makers, or of some eunuch priest lying drunk with idle timbrels. Here is Liberty Hall! One cup serves for everybody; no one has a bed to himself, nor a table apart from the rest.

Juvenal, 8.171. Translated by G. G. Ramsay, (click for link).

Martial is particularly scathing about the clientele of the bars, especially a character called Syriscus, who did not recline to eat when at the popina, as was the custom. Such practices, along with eating in public, were seen by the elite as socially incorrect behaviour, so in this satire Martial is highlighting the Roman class distinctions.

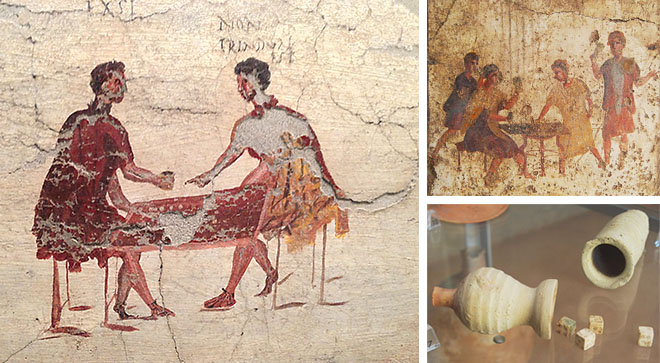

Gambling

Gambling was also often linked with the bars — despite it being outlawed. The dice box had such a distinctive sound, it could give away the not so secretive gambler, as Martial highlights (V.LXXXIV). Such games of chance might also result in a punch up, as depicted in a fresco from Pompeii, where the outcome of the throw of the dice sparks a fight between the two players.

Left and top right, wall paintings from Pompeii showing gaming scenes. Bottom right, dice boxes (fritillus) and dice. Images: Paula Lock.

Exercise: Follow this link 5. Concerning gamblers, jot down the main points set out by these laws. What is allowed and what isn’t?

Women

Overall, the sources suggest that the Roman bars were very much a place for men — where we do find women portrayed, they tend to be barmaids rather than customers.

For example, electoral graffiti written outside a bar at Pompeii names three women — Maria, Aegle and Zmyrina — who it is thought worked in the bar. The names are exotic (Aegle and Zmyrina are of Greek origin) and remind us of the multi-cultural nature of the labour force of the Roman world and that many different languages and accents would have been heard around these cities.

Left, wall painting from a bar in Pompeii showing a barmaid serving drinks. Right, electoral graffiti, naming Zmyrina (CIL IV 7863). Images: Paula Lock.

In another graffito we find a rather popular barmaid called Iris, who has two admirers vying for her affections.

Severus: Successus the weaver loves the barmaid of the inn, called Iris, who doesn’t care for him, but he asks and she feels sorry for him. A rival wrote this. Farewell.

Successus: You’re jealous, bursting out with that. Don’t try to muscle in on someone who’s better-looking and is a wicked and charming man.

Severus: I have written and spoken. You love Iris, who doesn’t care for you. Severus to Successus. (CIL IV 8259, 8258)

Translation from Pompeii and Herculaneum: A Sourcebook, Alison E. Cooley and M. G. L. Cooley, (p.109, D105).

The poor reputation of some of these bars may have been the reason women did not venture across their thresholds. However, the Roman laws make it clear that such establishments were linked with prostitution, and therefore no place for a respectable woman. The association of the bar with prostitution was so ingrained that even if a woman entered one, she could be branded as a prostitute.

We hold that a woman openly practices prostitution, not only where she does so in a house of ill-fame, but also if she is accustomed to do this in taverns, or in other places where she manifests no regard for her modesty.

Dig.23.2.43.pr. Translated by Samuel P. Scott, (click for link).

Certainly, if the graffiti found in the bars are to be believed, some of the women associated with these establishments may have been rather free with their favours. However, to what extent these texts reflect reality is unclear — it could just be a case of male bravado.

Exercise: Follow the link here and search for the word ‘tavern’, what other laws can you find that relate to women and bars?

Despite the negative press handed out by the elite, the bars provided much needed refreshment to many. They were also a focus for social interaction, gossip and general well-being for the lower strata of society. As such they played a key role in the urban landscape of the city.

For Lucius, now revived, he can continue his day with a full stomach and a spring in his step!

Bibliography and further reading

Cooley, Alison, and M. G. L. Cooley. Pompeii and Herculaneum: A Sourcebook. Routledge Sourcebooks for the Ancient World. London; New York: Routledge, 2014.

Dalby, Andrew, and Grainger, Sally. The Classical Cookbook. London: British Museum Press, 1996.

Ellis, Steven, ‘Pes dexter: Superstition and state in the shaping of shop-fronts and street activity in the Roman world’ in Rome, Ostia, Pompeii: Movement and Space. Oxford, edited by Laurence, Ray, and Newsome, David J., 160-173. Toronto: New York: OUP Oxford, 2011. You can download a pdf of the chapter here.

Hermansen, Gustav. Ostia: Aspects of Roman City Life. Edmonton, Alta: University of Alberta Press, 1982. See pages 125-204.

Laes, Christian, and Ville Vuolanto, eds. Children and Everyday Life in the Roman and Late Antique World. S.l.: Routledge, 2016.

See especially, ‘Children and the Urban Environment: Agency in Pompeii’, Ray Laurence and ‘Age, Agency, and Material Culture in the Roman World: the Graffiti Evidence from Roman Campania’, Katherine Huntley (This book will be released October 2016.)

Laurence, Ray. Roman Pompeii: Space and Society. London; New York: Routledge, 2007. See pages 82-101.

Packer, James E. ‘Inns at Pompeii: A Short Survey.’ Cronache Pompeiane 4 (1978): 19480.

Toner, J. P. Popular Culture in Ancient Rome. Cambridge: Polity, 2009.