This month’s post has been written by Brittany Stone, M.A. student in Roman History and Archaeology at the University of Kent.

Rome, the Eternal City, is the largest municipality in Europe today, double the size of Paris’ inner suburbs and almost as large as the Greater London area. This fact is owed to the city’s vast history as the capital of its eponymous transcontinental empire. Rome’s rich history has allowed the city to grow and transform in unexpected ways, making the layout confusing and unusual to modern visitors. Walking through the modern cityscape today reveals echoes of the city’s past in both its layout and surviving monuments. Let us begin by defining the city limits throughout the centuries.

One of the most remarkable structures of Rome is its city walls. Rome owed its massive power to its violent and victorious history against surrounding peoples, especially in the city’s founding period. According to Rome’s foundation myth, by April 21st 753 BCE, Romulus, the city’s founder and namesake, had conquered the nearby Sabines and defined the limits of original Rome. This boundary line, called the pomerium, was continuously extended as the city’s population grew following each new subjection of outsiders (such as the Latins and Etruscans). As the city expanded, so did the area that needed defending from attackers and the city built fortification defenses around its perimeter. In the early period, this was an earthen wall with ditches surrounding the city but over time, Rome needed stronger walls, which was proven when the Gauls invaded Rome during the Battle of Allia in 393 BCE. According to Livy, Gauls from the north defeated the Roman army and simply entered the city. It was after this humiliating defeat that Rome constructed the Servian Walls, named after Rome’s sixth king Servius Tullius (who ruled two centuries earlier) because the walls were built on top of his boundary line.

Figure 1: Servian Wall in McDonalds, Termini Station, Rome

Under the Republic, Rome became even more powerful before flourishing further in the Imperial Age. For centuries the population of Rome grew but the city was so confident in its dominance that there was no need to expand the city’s defenses. However, that changed during the Crisis of the Third Century. Rome’s economy was disrupted, expansion expeditions ceased, and barbarians were invading. For the first time in nearly 700 years, the city of Rome needed new defenses. Under Emperor Aurelian in 270 CE, new wall fortifications were commissioned as threats on Rome from barbarian attacks were imminent. The quicker these walls were built the better. This phase of rapid building is easily noticeable as one tenth of the Aurelian wall is composed of whatever buildings happened to be in the way, such as the Castrense amphitheatre which can still be seen within the wall structure today. Aurelian’s Wall, nearly double the length of the Servian walls, was sufficient for the time but has since gone through several expansion periods, the most dramatic of which occurred during the reign of Honorius when he doubled the height of the wall. However, this effort was not enough to stop the sack of Rome by the Goths in 410 CE. The wall is still a major component of modern Rome and even has its own museum, the Museo della Mura. Located on the Via Appia, the Museum of the Walls is in the largest and best preserved gatehouse, now called Porta San Sebastiano.

Now let’s look at the city itself. How is the area laid out? Rome is the city of seven hills. These hills have defined the area and been marked out as places of importance, but they have changed shape over time. Much of the inhabitable area of Rome had been intentionally manipulated through the efforts of politicians. For example, the most important hill of Rome, the Palatine, the centre of Rome’s hills, was the founding site of the city, said to have been founded by the mythical Romulus. It was, in legend, where Rome’s first leader had his house, a hut that Rome sanctified and constantly rebuilt. From then on, emperors used the special space as the site of their own homes, notably Augustus, Domitian, and Septimius Severus. Today, modern viewers can walk among the remains of these houses whose displays of grandeur are still evident. They can also see the space where the Circus Maximus once stood. Around the corner from the Palatine Hill is another important hill from ancient times, the Capitoline Hill. Now home to one of Rome’s finest museums, the Capitoline museum contains a history of the city through art, such as its massive collection of impressive statuary excavated from around the city, and building structures, including a few ancient temples such as the oldest Temple of Jupiter and the mysterious Temple of Veivois. It is in the valley between these two hills that the infamous Roman Forum is located.

Aside from the hills, a vital component of Rome’s topography is the Tiber River, which now runs through the city but in ancient times flowed to the left of the inhabited region. As Rome was based near the Tiber, originally the entire city was a swampy marshland due to the constant flooding of the river, but drainage platforms and construction sites throughout the Republican period transformed the land into a livable space. A significant portion of the area, however, to the northwest of Rome’s hills, remained marshland. This area, located just outside of the Servian walls, was known as the Field of Mars (Campus Martius) and remained uninhabited until the time of Augustus, noted in Strabo’s praises of the beautifully natural space (5.3.8). However, under Rome’s first emperor, the city expanded and this area became the construction site of various important structures, including the Pantheon, the Mausoleum of Augustus and the Ara Pacis.

The next great construction phase of the Campus Martius occurred under Domitian when he rebuilt a portion of grounds due to a great fire in 80 CE. Using this opportunity to establish himself as ruler, Domitian contributed new building structures to the area. Most notably, Domitian added his own theatre, stadium, and the Odeon. Although these buildings have not survived, the modern square called Piazza Navona has been built over the remains of Domitian’s stadium, giving the “square” the odd shape of an elongated oval, typical for stadiums. Finally, during the reigns of Hadrian and the Antonines, the region was equipped with a main road designed for funerary processions. During this time, temples and columns were additionally constructed in this region. Today, this region of the modern city still relies on its past, as the streets follow the same design and layout as they were set hundreds of years ago, making a stroll along Via dei Coronari a walk through time.

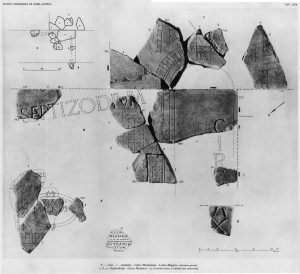

We owe a good deal of our understanding about the ancient layout of Rome to the Severan Marble Plan, an 18-metre wide by 13-metre high marble slab map of the city of Rome. Commissioned by Emperor Severus between 203 – 211 CE, this map is a 1:240 scale depiction of the city that originally hung on the inside of the Temple of Peace in the Imperial Forum. Due to scavenging over time, only about ten percent of the map has been recovered, composed of over a thousand tiny pieces of marble. Items that have been preserved on the plan include the Colosseum, the Circus Maximus, and the Theatre of Pompey. The map is orientated with south at the top and its perimeter conforms to the edge of the slab rather than political boundaries as maps do today. Despite the struggles in understanding this map, the Severan Marble Plan is still a valuable piece of architectural history that reveals information that may otherwise not have been known, such as the location of the Dacian Gladiatorial Training School, the Baths of Trajan, and the elusive Severan Septizodium.

Figure 2: Plate 17 of the Severan Mable Plan, courtesy of Stanford Digital Forma Urbis Romae Project

The city of Rome has experienced much change over its long history, from centuries of urban development to multiple sacks of the city to the rise of Christianity. Despite this, Rome has managed to cling to its illustrious past in conspicious ways through iconic monuments such as the Colosseum, the Arch of Constantine, and Trajan’s Column; as well as with architectural wonders such as the Roman Forum, the Imperial Fora and Trajan’s Market.

Rome’s past, however, is preserved in more forms than immediately meet the eye. The history of the city is everywhere: in the form of Rome’s defensive walls, in the layout of Rome’s roads, and within Rome’s defining topographical features like the Tiber River and the Seven Hills of Rome. Modern tourists are not limited to walking down the Via dei Fori Imperiali in order to walk in ancient Rome because ancient Rome survives and influences so much more of the modern city of Rome.

FURTHER READINGS

Primary Sources

- Livy. History of Rome.

- Strabo. Geography.

- Tacitus. Annals.

Secondary Sources

- Claridge, Amanda, Toms Judith and Cubberley Tony. Rome: An Oxford Archaeological Guide. New York: Oxford University Press, 1998.

- Coarelli, Filippo. Rome and Environs: An Archaeological Guide. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2014.

- Galinsky, Karl. “Memoria Romana: Memory in Rome and Rome in Memory,” Memoirs of the American Academy in Rome. Supplementary Volumes 10 (2014): Iii-193. JSTOR

- Patterson, John R. “The City of Rome Revisited: From Mid-Republic to Mid-Empire,” The Journal of Roman Studies 100 (2010): 210-32. JSTOR

- Stanford Digital Forma Urbis Romae Project. 2018. Available online.