This month’s blog is by Catherine Hoggarth – through the eyes of Lucius – we view the Tiber and its bridges on the Ides of May in AD 73. Catherine is a PhD student at the University of Kent, much of this blog draws on her own research on the bridges of Rome.

It is the ides of May in AD 73, in Rome Lucius and his father are making their way down to the Forum Boarium, a large market area located alongside the Tiber river. This area was public space and used as a cattle-market but it was also an ancient and important area of Rome. It was to this area that the infant founder of Rome, Romulus and his brother Remus, floated in a basket catching on a fig tree, some say though the divine intervention of the god of the Tiber, and were then suckled by a she-wolf and fed by a birds before being rescued. Today, Lucius and his father are heading, not to the market but to the Sublicius bridge to witness the rituals of the Argei. At the Liberalia (see a Glimpse of Teenage Life in Ancient Rome), Lucius and his father had visited one of the shrines holding the figurines of the Argei that will feature in the ritual, today, at Tiber.

Romulus and Remus and the she-wolf, the Capitoline museum, image Catherine Hoggarth.

When they arrive at the river bank the area is a hive of activity, the market place is a cacophony of noise with traders shouting and cattle lowing, increased by those waiting to witness the procession. Lucius and his father find a spot on the banks of the Tiber just above the giant Cloaca Maxima the drain for the Forum Romanum and surrounding valleys. Rumour has it that the emperor Augustus’s right hand man Marcus Agrippa once sailed a boat along the drain checking for repairs.

While they are waiting for the procession to arrive Lucius watches a multitude of small boats plying their way along the river, disappearing under the Sublicius bridge and pulling alongside the stone Aemilius bridge. Lucius stares down into the waters of the Tiber, he can see people fishing near the mouth of the Cloaca and knows that young men often take a swim in the river. Lucius would rather not swim in the river, he looks into its calm waters but knows a different side of the sacred Tiber, one that can inflict great damage on the city.

The single remaining arch of the Aemilius bridge in Rome, image Catherine Hoggarth.

Four years ago, when he was thirteen years old (AD 69) the city experienced one of the worst floods in recent memory. Lucius family lived just outside the flooding area but he vividly remembers a number of his father’s friends whose shops and homes were washed away or collapsed during the surge. The river had risen so quickly that there was little time to flee, huge trees and debris from city including wagons and building parts were deposited all over the city, blocking roads and damaging structures. The loss of much of the grain supply also caused food shortages adding to the misery of the city for some time after the water had receded. However, even though this was one of the worst floods in recent memory, the Roman’s took it in their stride. While the Tiber did destroy areas of the city on occasion, it also provided for the population; in the eyes of the Romans the Tiber was the supreme river and just as Cicero had, Lucius felt proud that his city was located at the most auspicious place on this most sacred river. Secretly he had also quite enjoyed accompanying his father around the flooded city in a small boat, it was like exploring a whole new world from the water.

Tiber high water levels in 2014 at the Aemilius bridge and debris left against the Ponte Sant’Angelo after the waters receded, images Catherine Hoggarth.

During the flood of 69 AD the Sublicius bridge, upon which Lucius now gazed, had been destroyed. This bridge was unlike any other in Rome, it was Rome’s first bridge and a sacred structure made completely of wood; no iron was allowed. When it was damaged, which was quite frequently, it was quickly rebuilt and stood as a reminder of Rome’s past triumphs. One of Lucius’s favourite hero’s of Rome was commemorated by a statue just near where he now stood; Horatius Colces was one of Rome’s great men (commemorate on the shield of Aeneas), he had defended the bridge single-handedly against an Etruscan army allowing his fellow Roman’s to cross the bridge to safety. As the bridge was wooden, Horatius was able to defend the bridge while it was cut down behind him, preventing the attackers passage into Rome. According to Livy he then dived into the Tiber and swam to the banks of Rome without the loss of his equipment or weapons, emerging a hero. However, Polybius believed that Horatius did not survive the swim across the river, sacrificing himself for Rome; Lucius prefers to believe Livy, he likes to think Horatius made it across.

Horatius Cocles defending the Sublicius bridge on a coin from the reign of Antoninus Pius (138-161 AD) from Fröhner. W (1878) Les Méaillons de l’Empire romain depuis le Règne d’Auguste jusqu’à Priscus Attale.

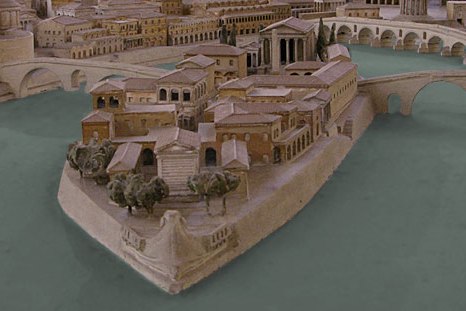

Remembering the great deeds of the past was important to the Romans and for Lucius looking at the wooden bridge reminded him of Rome’s history. Yet in the adjacent Aemilius bridge he also saw Rome’s current strength and power; the solid stone bridge was a symbol of Rome recognised across the empire. Maintaining the wooden bridge was a source of pride and an important act of commemoration but crossing the bridge was another matter. Lucius did not like to cross the Sublicius bridge it creaked and groaned and you could sometimes see the boats passing underneath the roadway. He preferred to walk on the solid stone of the Aemilius bridge and under the great arch which Augustus had erected at the end of the bridge. He also liked to look at the imposing prow of the Tiber island which was shaped like a huge boat and seemed to be heading toward the bridge. Sometimes he was even allowed to stop at the edge of the bridge and throw a votive offering (an object deposited in a sacred place) to the god Tiberinus.

The god of the Tiber River. Rome, Musei Vaticani, image Catherine Hoggarth.

Plastico di Roma Imperiale from the Museo della Civiltà Romana, image Catherine Hoggarth.

Lucius musings are suddenly interrupted by the arrival of the procession; he can see the Pontifex Maximus and the Vestal Virgins moving toward the Sublicius bridge carrying the twenty-seven or thirty argei (effigies) in the form of men, which they will throw into the Tiber.

Lucius is curious about this ritual, he has seen it before but it not sure why it is performed. Ritual and history are very important to the Roman’s as Lucius’ father explains; even though the origins of the ritual are obscured (Dionysius of Halicarnassus linked the ceremony to an archaic Greek ritual of human sacrifice) it was still an essential ritual purification of the city which had been observed over many lifetimes, continuing these traditions was a central part of the Roman life.

Prior to reaching the bridge the procession had visited the shrines of the argei around the city collecting an effigy from each. The effigies from each region would absorb the pollution or the bad luck of the city and then be cast into the Tiber to be carry away. As Lucius father finishes speaking the procession reaches the bridge, the Pontifex Maximus, literally meaning greatest bridge-builder was the highest priesthood in Rome, Julius Caesar had been a Pontifex Maximus but since Augustus held the title, it has been passed from emperor to emperor; the current emperor, Vespasian, is now wearing his toga of office which he has drawn up over his head. Among his other duties he was responsible for the oversight of the vestal virgins, who were now walking out onto the bridge.

Augustus in the dress of the Pontifex Maximus. Rome, Musei Vaticani, image Catherine Hoggarth.

There were between four and six Vestal Virgins living in the Temple of Vesta in the Forum Romanum, they were all from good families and chosen for the role by the Pontifex Maximus between the ages of six and ten years old. They served for 30 years during which time they maintained a vow of chastity; other duties including maintaining the perpetual fire in the temple of Vesta, fetching and drinking water from the sacred spring and caring for the sacred objects within the temple. The Vestals were held in very high regard in Rome and any failure in her duties led to harsh punishment which could include being buried alive at the Collina gate.

All the important members of the procession are now lined along the bridge, they can now be seen by all those standing alongside both banks and from the boats on the river itself, the effigies are then given to the Tiber. As the rites are being conducted on the bridge Lucius is distracted by the little effigies bobbing along on the Tiber. He starts to wonder which one will be the first to reach a small ferry which is waiting alongside the bank; he picks one he is sure will win and watches its progress avidly. As the procession moves away from the bridge Lucius and his father move back toward the market, where he hopes his father will purchase them a snack before they head off to the other business of the day.

Bibliography

Aldrete, G.S. (2007), Floods of the Tiber in Ancient Rome (London, John Hopkins University Press).

Beard, M., et al. (1998), Religions of Rome (Cambridge; New York: Cambridge University Press).

Coarelli, F. (2007), Rome and Environs, An Archaeological Guide (Berkeley and Los Angeles, California, University of California Press).

Favro, D. (1996), The Urban Image of Augustan Rome (Cambridge, Cambridge University Press).

Lott, J.B. (2004), The Neighbourhoods of Augustan Rome (Cambridge, Cambridge University Press).

O’Connor, C. (1993), Roman Bridges (Cambridge, Cambridge University Press).

Platner, S.B., and Ashby, T. (1929), A Topographical Dictionary of Ancient Rome (London, Oxford University Press).

Robinson, O.F. (1992), Ancient Rome: City Planning and Administration (London and New York, Routledge).

Richardson, L. (1992), A New Topographical Dictionary of Ancient Rome (London, John Hopkins University Press).

Steinby, E.M. ed. (1993 – 2001), Lexicon Topographicum Urbis Romae (LTUR) 6 Vols., (Roma: Edizioni Quasar).

Taylor, R. (2000), Public Needs and Private Pleasures: Water Distribution, the Tiber River and the Urban Development of Ancient Rome (Roma, L’Erma di Bretschneider).