A reasonable expectation that subscribers have of their favourite magazine is that its publication frequency offers a hint as to how many numbers they may expect for their money. One expects quarterlies to appear four times a year, and in that same time span weeklies should surely do 52 issues. You may however have noticed that some periodicals are more generous than they let on. Monthlies, for instance, will often publish no less than thirteen numbers per year. This is a long-standing custom that we already find in the eighteenth century. In fact, the Lady’s Magazine did this too.

LM, XXXIX (1808). Image © Adam Matthew Digital / Birmingham Central Library. Not to be reproduced without permission.

Issues that appear outside the regular run of a periodical are referred to as ‘supplements’. Periodical scholars think of these as an interesting oddity for more than just the temporal irregularity that they present. We want to know what the need was for such extraneous issues. Generally speaking, supplements supply content for which inclusion in the regular issues of the magazine is not deemed opportune, but that the publishers want to be associated with the periodical all the same. They may be there for a variety of different reasons that depend on the particular case. The predominant concern will usually be commercial, and, having to do with the periodical’s market positioning. In the Victorian period ‘Christmas numbers’ for instance became a popular way to cash in on the holidays with an easily marketable, self-contained publication that readers could look out for.

The annual ‘Supplement’ of the Lady’s Magazine too appeared in December, although the magazine had a regular number in that month as well. It starts in 1774 and carries on until the end of the ‘First Series’ in 1818, and over that time undergoes no radical changes. Due to the lack of circumstantial information on the magazine in general, we cannot be sure whether the Supplement came free with the December issue, or whether readers were charged for it. As is often the case with supplemental publications, at least some readers or librarians must have thought of this extra instalment as not genuinely belonging to the series, because the surviving bound volumes of the magazine often do not have the Supplements in them.

The Lady’s Magazine shares all the editorial quirks and inconsistencies characteristic of eighteenth-century miscellanies, and it is not immediately apparent which function the Supplement would have fulfilled. Despite its appearance in December, there is nothing seasonal about it. Its contents do not differ significantly from those of the regular issues, and all the same genres found in the regular run appear here too. The Supplement seems to differ from the regular issues in two respects only. The first is that the usual editorial section, normally found on the back of the table of contents, is now replaced with an advertisement for the upcoming January issue. This contains enticing references to new series that the magazine had planned for the following year, and an assurance that regular favourites such as agony aunt column ‘The Matron’ would be continued. The advertisements can therefore serve as an indication of which kinds of content were especially appreciated by the readers. For instance, in 1776 they are told that in the next year there would be ‘more particular and minute Accounts of the Female Dress’. There are also always a few paragraphs reminding the readers of the rationale of the magazine, and calling upon them to continue sending in contributions. This points to one plausible main function for the Supplement: it was likely issued to convince readers to renew their annual subscriptions.

LM, VII (1776). Image © Adam Matthew Digital / Birmingham Central Library. Not to be reproduced without permission.

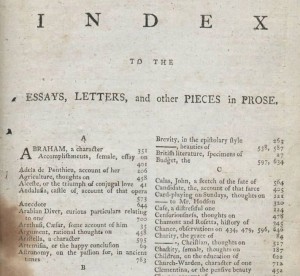

A second distinguishing feature of the Supplement is the inclusion of the yearly Index, an often inaccurate and incomplete list of the Lady’s Magazine’s contents over the past year. Issuing such an index encouraged the readers to retain their copies of the magazine for later consultation. The Supplement’s abovementioned advertisement also includes instructions to the binders concerning where some of the loosely inserted illustrations needed to go; additionally useful to us today because these are sometimes the only mention we get of long vanished items. The magazine’s inducing the readers to preserve the magazine obviously goes against the disposability often associated with periodical publications. If the readers hold on to their Lady’s Magazines and ideally even have them bound into annual volumes to form actual books, then the magazine is no longer ephemeral like other periodicals. It would thereby gain the prestige deserved for its aim to be ‘the Ornament and Amusement of the Fair’ (Suppl. 1776).