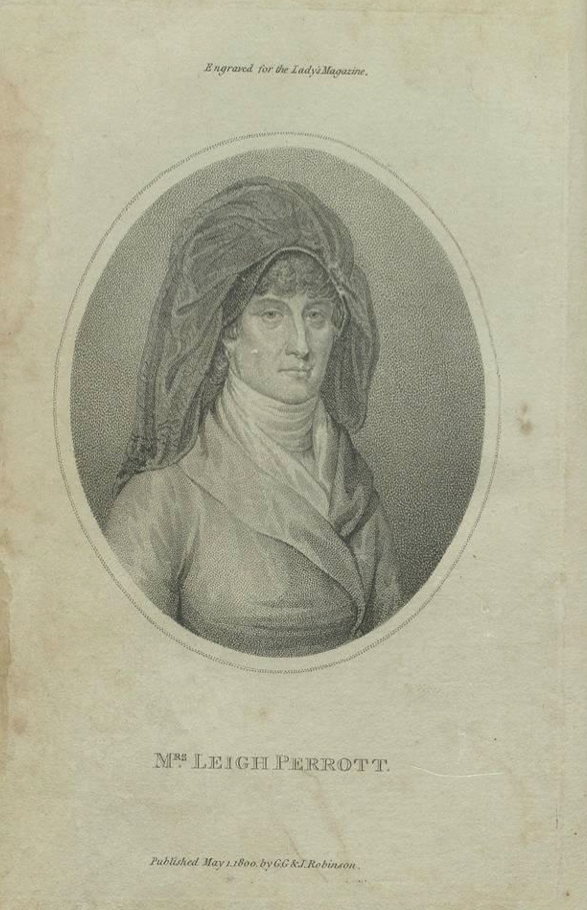

Detail from the frontispiece to The Ladys Magazine , or Entertaining Companion for the Fair Sex for 1780 .

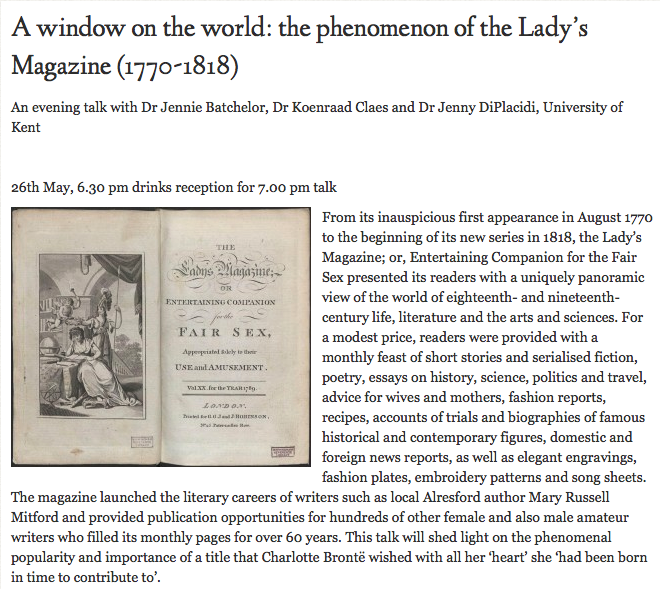

Last week, Koenraad posted about our project trip to the biennial BARS (British Association of Romantic Studies) conference at Cardiff. It was a brilliant event: the papers were wide-ranging, innovative and rigorous; the company was convivial and generous.

One of the great pleasures for me, beyond participating in our own project panel, was chairing another on ‘The Minerva Press and the Romantic Print Marketplace’, convened by Yael Shapira (Bar-Ilan University) and comprising papers by Yael, Elizabeth Neiman (University of Maine), Hannah Doherty Hudson (University of Texas, San Antonio) and Olivia Loksing Moy (CUNY). The pleasure was threefold: hearing the research of four scholars who used various disciplinary approaches to make clear just how important and influential William Lane’s much-derided press was; allowing me to revisit an immense body of page-turning work that I have been long interested in but realise I have only ever really skimmed the surface of; and making me think more about the relationship between the popular fiction and the Lady’s Magazine.

In some ways, the Lady’s Magazine is the Minerva Press fiction of the Romantic periodical marketplace. Both magazine and imprint are indelibly linked in the scholarly imagination with the popular (in a largely pejorative sense), the fashionable (or even cynically opportunistic), the feminine, the non-professional and the ephemeral. These are associations that we vigorously seek to interrogate and dispel on this blog and in a more sustained way in the project itself, just as the speakers at BARS did so convincingly in their papers and continue to do in their wider research.

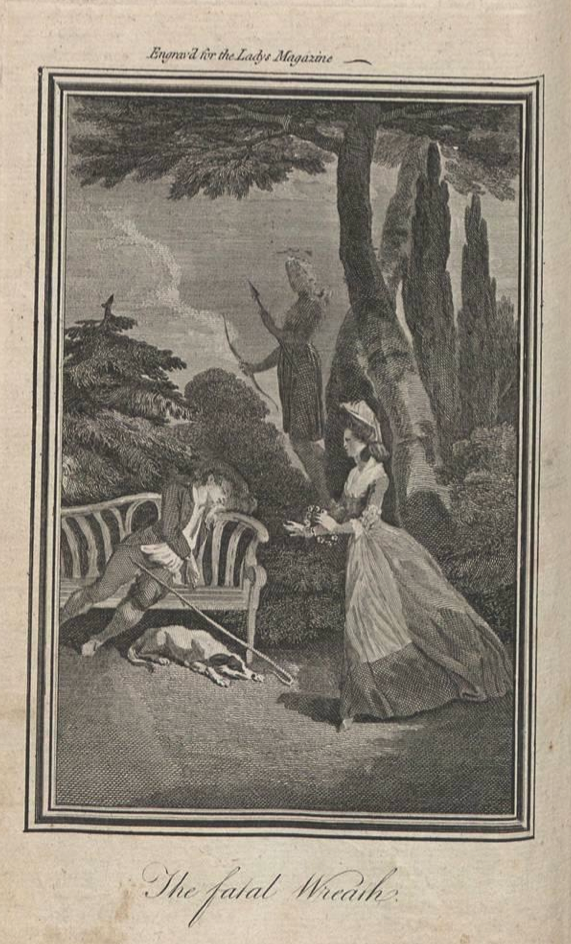

LM, XXXIII (Jan. 1802). Image © Adam Matthew Digital / British Library. Not to be reproduced without permission.

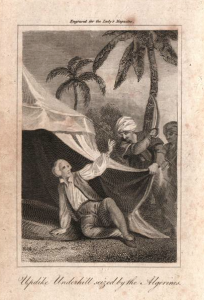

But I have long fantasised about more meaningful and demonstrable connections between the William Lane’s Minerva Press and the Lady’s Magazine. I’ve always been curious, for instance, by the importance of Minerva, Roman goddess of wisdom and strongly associated with the arts and with war, to the magazine. A Minerva figure is present in almost all of the annual frontispieces to the magazine in its first three decades, although eventually she begins to be usurped by Britannia. Usually, she is figured ushering women readers who carry the magazine in their hands, along the path of, or towards the temple of, wisdom. Was this at least partly on Lane’s mind when he adopted the name for his press? Was he hoping that some of the popularity of Robinson’s magazine might rub off on his new imprint?

I’ve also wondered if Lady’s Magazine authors (especially the fiction writers) might have subsequently found their way to Lane’s door or even, more tantalisingly still, moved from Lane to the Lady’s. Minerva Press novels are not monolithic in the way the shorthand term sometimes suggests. But nonetheless, the press’s often sentimental or Gothic fiction commonly return to similar themes of affect, economics and social injustice that preoccupy writers for the magazine, although each renders them differently. We are piecing together various bits of evidence on possible authorial migration between the Minerva Press and the Lady’s, which I for one find fascinating, and we’ll tell you about that in due course.

One thing we can say now, though, was that the magazine did stick up for Minerva at a time when other magazines and, in particular, the Reviews were doing just the opposite. Nowhere is this more evident than in a wonderful article entitled ‘On Criticism’ that appeared in the magazine for November 1804. The contributor, who went by the pseudonym ‘A Lover of Candour’, targeted the old-boy networks, shady credentials and self-interest that s/he saw as underpinning contemporary reviewing practices.

We simply do not know who ‘A Lover of Candour’ was, but s/he claimed to be ‘in the secret’ (577) of the trade and wanted to disabuse readers of the Lady’s of any fantastic notions that they might have that reviewers might be objective or even qualified to pronounce, with such authority, on the relative merits or demerits of the texts on which they opined. Writers who hoped their books might get ‘noticed’ needed some ‘interest’, that is to say, connection with potential reviewers or Reviews to ensure their work would appear on their radar (577).

Even if that interest could be relied upon, however, no author could be guaranteed a fair hearing. How could they be when their works were vulnerable to the whims of ‘a self-created dictatorship […] of anonymous individuals, subject to no dissent, no controul, no examination’ (577)? Reviewers might be people of ‘great learning’, but book learning was no guarantee of ‘genius’ or ‘taste’ after all (577). Authorial ‘merit’ was scarcely enough to secure a favourable review: ‘ for if the author is known, it is frequently rather him than his work that is reviewed’ (578). And readers were simply not trusted to make up their own minds on such important matters. The common long eighteenth-century reviewing practice of printing extracts of the reviewed work might seem to allow readers to ‘judge[e] for themselves’, but only on the basis of strategically excised passages, decontextualised and calculated for particular effect (578).

This general invective against reviewing conventions achieves a sharper focus when ‘A Lover of Candour’ turns to a particularly egregious abuse of privilege as s/he sees it, in the form of a recent issue of the Monthly Magazine. In it, ‘its editor or editors’ in a ‘half-yearly review’ ‘condescend[ed] to pass upon poor authors, whom they do not even deign to read’ by damning a class of the profession through cursory attention to a few examples: ‘A short article, under the head of Novels, concludes with saying, that “probably Lane might furnish a list of a hundred more but that they have names all, or perhaps more than all, that are worth reading”‘ (578).

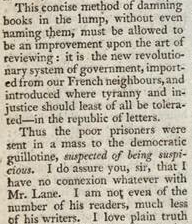

LM, XXXV (Nov. 1804): 578. Image © Adam Matthew Digital / British Library. Not to be reproduced without permission.

This tendency towards ‘damning books in the lump without naming them’ – of homogenising books and authors (the notorious and ever multiplying body of circulating library trash) so as to avoid having to read them – is strikingly likened by the Lady’s contributor to ‘the revolutionary system of government, imported by our French neighbours’ (578).

We don’t have to believe the ‘Lover of Candour’ when they say that they had ‘no connexion with Mr. Lane’ (578). And we know that some writers for the magazine did, in fact, have dealings with Lane and the Minerva Press. But regardless of whether this particular author did or did not have personal reason to defend Lane, what interests me most is that s/he felt that they could defend Minerva and expose the ‘tyranny’ of reviewing in this particular periodical. No doubt this was, in large part, because the Lady’s Magazine strikingly did not publish regular reviews of novels with the regularity of even usually in the form that most of its rivals did (but that’s a topic for another blog post). Surely, though, it must also be because s/he recognised that the magazine embraced different ways of thinking about contemporary fiction; that, foreshadowing chapter five of Northanger Abbey (published in 1818 but originally sent to Crosby in 1805, a year after this article appeared), it railed against the ‘abuse’ of reviewers who dismissed the ‘labour of the novelist’ despite the ‘wit’ and ‘taste’ they displayed or the ‘pleasure’ they elicited in their readers.

The ‘Lover of Candour’ may not have been Lane’s friend, but the magazine to which s/he sent ‘On Criticism’ was undoubtedly sympathetic to his press and the many popular writers who published with it. One of our many tasks, BARS reminded me, was to see how far such sympathy extended in the Lady’s Magazine promotion of the careers of individual authors.

Dr Jennie Batchelor

School of English

University of Kent