LM X (May 1779). Image © Adam Matthew Digital / Birmingham Central Library. Not to be reproduced without permission.

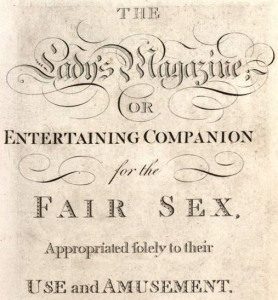

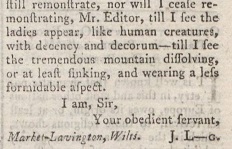

In her recent post on ‘J. L-g’, one of the hundreds of signatures appearing under contributions to the Lady’s Magazine, my fellow research associate Jenny DiPlacidi pointed out that the contributor who used this signature was situated in Market Lavington. I have to admit that I have not yet consulted many sources on the history of Wiltshire, but I will venture a guess, and assume that it was not a major hub of the late-eighteenth-century periodical press. However, the fact that someone from there was a frequent contributor did not surprise me. Our regular readers will know that a large part of the magazine’s content was supplied by amateur reader-contributors, who sometimes are helpfully forthcoming on their whereabouts, and these locations are spread all over the United Kingdom. When possible, the locations of authors will be included in our annotated index, parts of which will be published in the near future. This is the first in a series of blog posts to discuss the many uses of this kind of information.

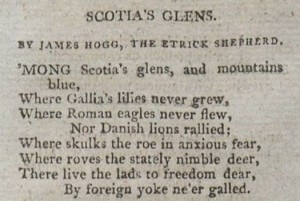

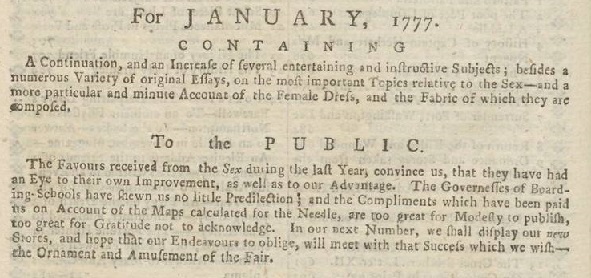

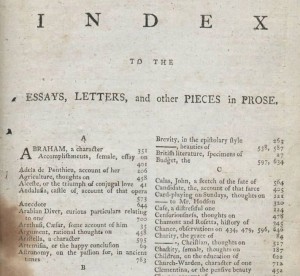

Scholars may want to know where contributors were based for several reasons. A location can be a great research lead when studying individual authors. When you are, for instance, looking into a contribution with a common signature such as “Camilla”, you will jump for joy upon discovering that this particular Camilla must be sought within the more manageable research context of the town of Cambridge (click image for larger version):

Lady’s Magazine devotees like myself, who wish to find out more about this publication as a whole, may wish to use this data to draw up so-called ‘prosopographies’ of people associated with the magazine. ‘Prosopography’ (emphasis on the third syllable) can be best understood as the practice of drawing up descriptions of groups of people about whom little precise information can be found individually, but about whom at least a few shared factors are known, on the basis of which we can get some idea of what they shared, and how they differed. You could for instance chart how different parts of the world are proportionally represented in the magazine, or, combined with the genre classifications and tags by the aforementioned Dr. DiPlacidi, which regions tended to furnish which types of content. Because for the Lady’s Magazine the categories of readers and contributors overlap, mapping the contributors will at once allow you to make cautious surmises about the geographical distribution of the readership as well, ever a problematic issue with older periodicals because data on subscription is inevitably scarce, and patchy at best.

LM XXI (Oct. 1790). Image © Adam Matthew Digital / Birmingham Central Library. Not to be reproduced without permission.

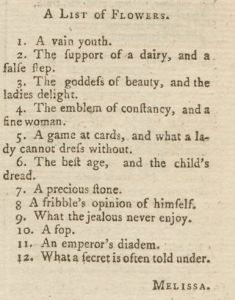

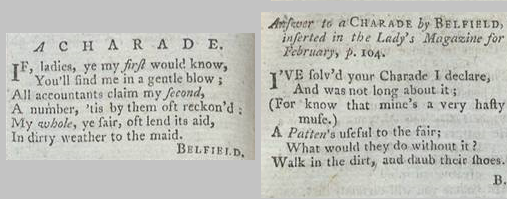

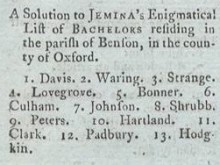

For about one tenth of the contributions per annual volume on average, the magazine will tell you straightforwardly where its contributors were based. It does this often by giving a location with the signature appearing under contributions, as in the example of ‘J. L-g’ given above, or by telling you a bit more about the contributors in its recurrent editorial “To our Correspondents” columns and the internal advertisements in the annual Supplement. At other times, it pays to read the contributions carefully, as some authors will tell you where they live somewhere within, or talk about other contributors whom they happen to know more about. Finally, some pieces discuss topics of extremely local interest, a case in point being the many submitted enigmatical lists of (eligible?) bachelors in specific rural situations, their secluded hiding place now to be discovered by every fair reader adept at solving puzzles.

We are busily at work on our index and are now about two-thirds into the covered run of the magazine, though we obviously will continue to update the index with new findings after it has gone online. We will soon be able to provide a few basic charts indicating geographical patterns in the magazine’s authorship, but at this early stage of our research some preliminary observations may serve to illustrate the use of these locations, and suggest some issues that I will address in the future instalments in this series. The first of these is that the Lady’s Magazine seems to have been foremost an English publication. Irish, Scottish, Welsh and even colonial locations appear, but in far lower numbers than English ones. While the relative demographics of the different British territories of course are relevant, the number of contributors indicating a location outside of England is conspicuously low. This would argue, though not conclusively, that the magazine also had relatively fewer readers in these places, and begs the question whether this hypothetical predominantly English audience is reflected in the selection of republished content, and its diverse ideological implications. Secondly, although every region of England appears to be represented, a disproportionately large part of the located contributors lived close to the magazine’s publishing office in Central London. With locations in London it is taken for granted that the reader will know where to place them, as even for less fashionable areas only the street name is stated.

We hope that you are as excited as we are about getting the figures behind these observations, as well as many others that will allow us (and that means you too) to finally give this pioneering and vastly influential periodical the scholarly attention that it deserves.