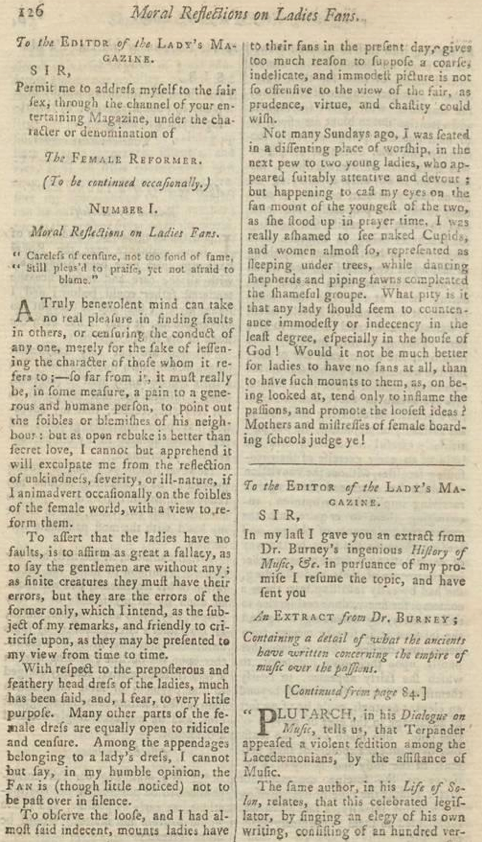

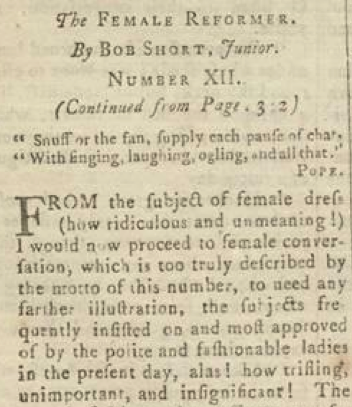

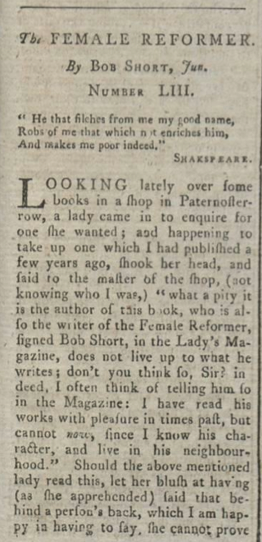

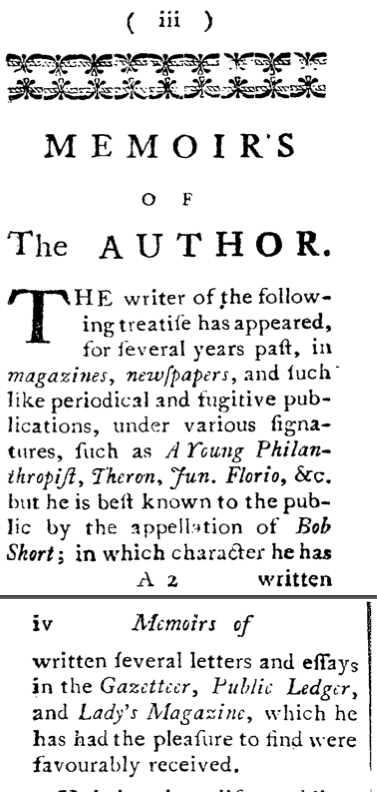

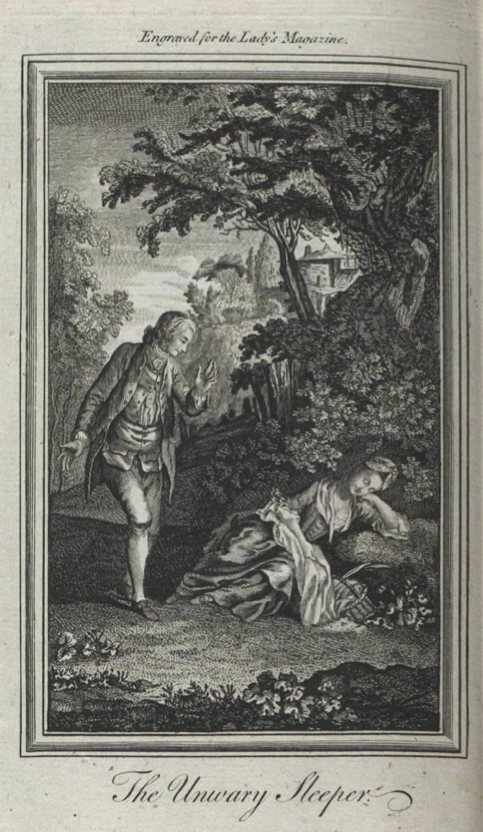

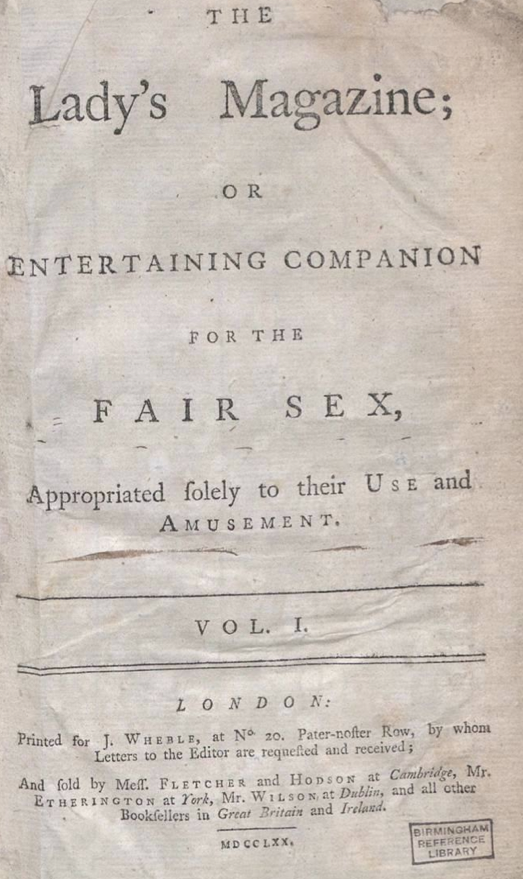

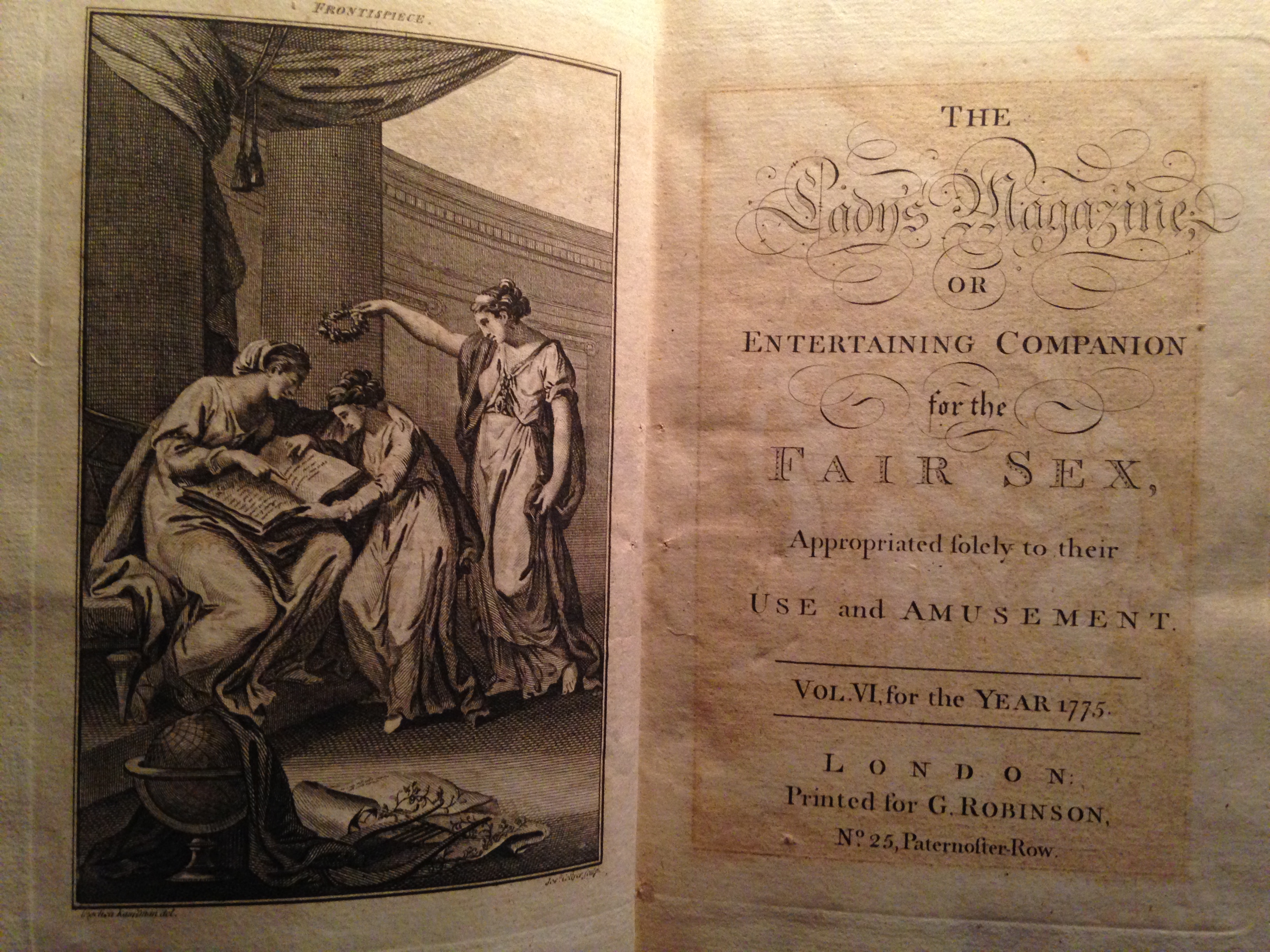

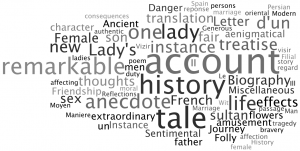

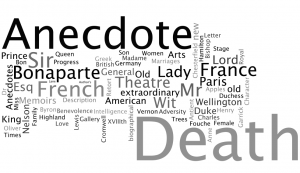

The discourses on fashion in the Lady’s Magazine (1770-1832) are, as we have seen, complex and multifaceted. While I have discussed some of the ways fashion appears in the magazine previously, in today’s post I would like to draw attention to the representation of fashion in three distinct genres: the serial novel, the opinion piece, and the advice column. My decision to give a brief overview of how fashion appears within these three genres is precisely because of the difficulties a researcher or reader would find in attempting to reconcile its representations across the genres. This is, of course, also true within genres; different serial novels offer sharply divergent opinions on social issues central to the magazine’s readership; likewise readers would receive distinctly dissimilar guidance depending on the authorship of an advice column. Nonetheless, by examining fashion across the genres rather than within one, it is possible to gain a better understanding of 1) the competing forms that discourses appeared in within the periodical and 2) how the eighteenth-century reader would have experienced these divergent representations.

My decision to give a brief overview of how fashion appears within these three genres is precisely because of the difficulties a researcher or reader would find in attempting to reconcile its representations across the genres. This is, of course, also true within genres; different serial novels offer sharply divergent opinions on social issues central to the magazine’s readership; likewise readers would receive distinctly dissimilar guidance depending on the authorship of an advice column. Nonetheless, by examining fashion across the genres rather than within one, it is possible to gain a better understanding of 1) the competing forms that discourses appeared in within the periodical and 2) how the eighteenth-century reader would have experienced these divergent representations.

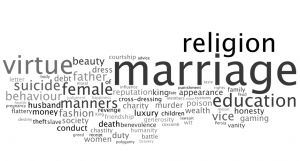

Fashion is merely one subject among hundreds that could be used to demonstrate this point, but it is a subject of perpetual fascination to me because of how discussions of it are consistently bound of with debates on morality, modernity, gender and sexuality.

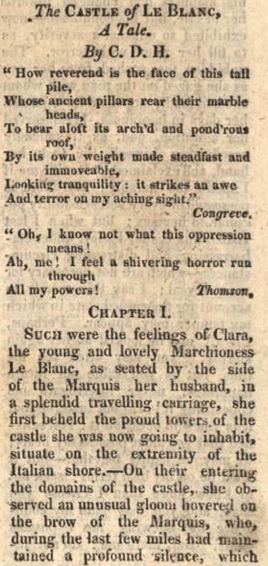

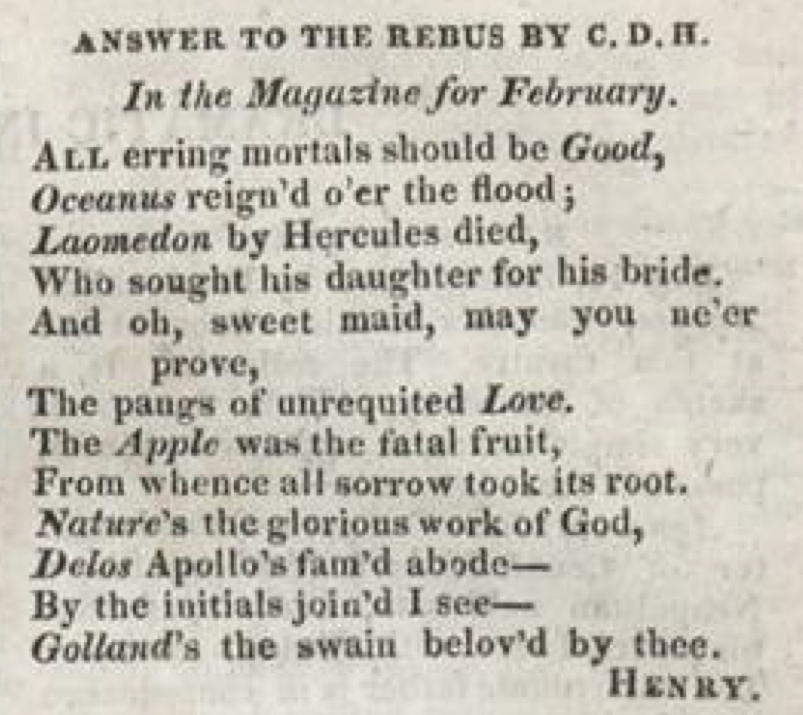

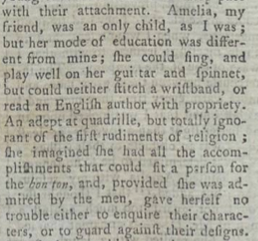

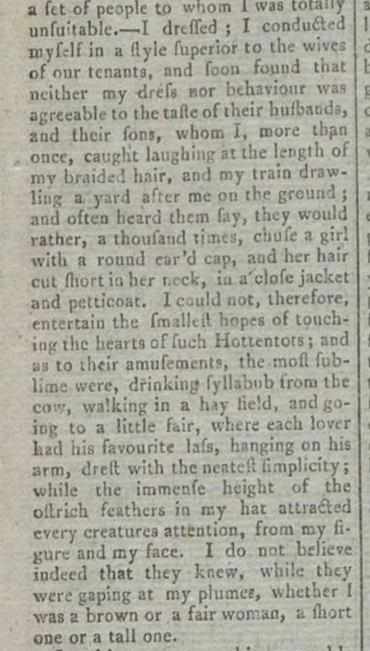

The anonymously authored serial novel The Dangers of Dissipation (1783-85) features a first-person narrator, Maria Wilding, who is a pleasure-seeking young lady whose tendency towards  dissipation (as the title indicates) puts her in dangerous situations, and who is most fond of admiration. This propensity carries on after she is married to the highly moral Mr. Wells, and causes her some mortification in the countryside when her fashionable dress renders her the object of ridicule rather than admiration to the local rustics, who she: ‘more than once, caught laughing at the length of my braided hair, and my train drawing a yard after me on the ground; and often heard them say, they would rather, a thousand times, chuse a girl with a round ear’d cap, and her hair cut short in her neck, in a close jacket and petticoat’ LM XVI [August 1784]: 412.

dissipation (as the title indicates) puts her in dangerous situations, and who is most fond of admiration. This propensity carries on after she is married to the highly moral Mr. Wells, and causes her some mortification in the countryside when her fashionable dress renders her the object of ridicule rather than admiration to the local rustics, who she: ‘more than once, caught laughing at the length of my braided hair, and my train drawing a yard after me on the ground; and often heard them say, they would rather, a thousand times, chuse a girl with a round ear’d cap, and her hair cut short in her neck, in a close jacket and petticoat’ LM XVI [August 1784]: 412.

But in spite of Maria’s dangerous desire to be admired, when she almost loses her husband’s regard entirely after he finds her in a compromising (though not guilty) position, she realizes that it is his love and esteem that are most important. Her husband pretends to flirt with another woman to make her jealous, and it is around a cap that this plot point and the novel culminate. Maria is assisting Miss Gataker at her toilet one day before they go out when her husband enters with ‘a new-fashioned hat [. . .] trimmed with lace and ribbon, in a very elegant taste, and presented it to Miss Gataker, desiring her leave to put  it on himself’ (LM XVI [January 1785]: 32). Maria is naturally very upset at her husband’s behaviour but especially when his friend, sir William, suggest that Mr. Wells give the cap to Maria and Mr. Wells replies ‘it will not become her’ (LM XVI [January 1785]: 32). Immediately after this Mr. Wells finally relents and confesses that both his flirtation with Miss Gataker and sir William’s repeated profession of love to Maria have been ruses to test her fortitude and fidelity.

it on himself’ (LM XVI [January 1785]: 32). Maria is naturally very upset at her husband’s behaviour but especially when his friend, sir William, suggest that Mr. Wells give the cap to Maria and Mr. Wells replies ‘it will not become her’ (LM XVI [January 1785]: 32). Immediately after this Mr. Wells finally relents and confesses that both his flirtation with Miss Gataker and sir William’s repeated profession of love to Maria have been ruses to test her fortitude and fidelity.

In the same issue, the Matron’s advice column [link] features an anecdote revolving around her cousin, Miss Partlett. Miss Partlett consistently dresses too young for her age, and Mrs. Grey just as frequently attempts to advise her against her fashion selections. In this column, Miss Partlett is ‘sallying forth’ in in a very fashionable ensemble featuring ‘an enormous feather’ that Mrs. Grey’s daughter attempts to reason with her, stating that propriety, not feathers, ‘render a woman worthy of esteem’ and that ‘every attempt that she makes to look younger than she really is, will have quite an opposite effect: it would only serve to make her more conspiculously ancient [. . .] Feathers, in the manner many young women wear them, put one too much in mind of funeral ornaments, upon the head of an old woman. They can make us think of nothing else, indeed, but a hearse’ (LM XVI [January 1785]: 27).

This is not the first time, or the last, that the Matron weighs in against older women dressing too young for their age. Her concern is not with fashionable attire in general; in other installments she compliments the expensive and beautiful dresses that her grandson’s wife wears, and she admires the elegant simplicity with which her granddaughter Sophia dresses. But the showy and cheap satin deshabille that her other granddaughter wears, and the age-inappropriate attire of Miss Partlett attract her censure. That is to say, it is not fashionable or modern styles in themselves, but inelegant or inappropriate choices that do not suit the wearer against which the Matron advises; becoming and stylish fashions that are genteel and elegant rather than tawdy or modish are always advised.

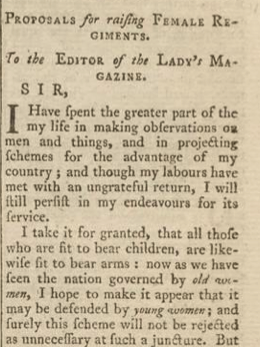

A serial opinion piece, rather wonderfully titled ‘One of the Leading Causes of Prostitution: The Dress of Servant Girls above their Stations’ appears in 1785 as well, and, though the writer claims not to want to usurp the place of the Mat ron in giving advice to the magazine’s readers, she must offer her opinion on the profligacy and depravity of women who become prostitutes. Two/thirds of these women, the writer claims (though offers perhaps unsurprisingly no source for this statistic) were previously servants. The cause of prostitution for these former servants is, the writer argues, ‘pride, and a desire of appearing out of their proper sphere’ (LM XVI [February 1785]: 96). Indeed, one of the most vexatious consequences of dressing beyond one’s rank is not a life of prostution (and consequently degradation, disease, squalor, unwanted pregnancy and early death): no, this writer finds the real disastrous effect is that it is no longer

ron in giving advice to the magazine’s readers, she must offer her opinion on the profligacy and depravity of women who become prostitutes. Two/thirds of these women, the writer claims (though offers perhaps unsurprisingly no source for this statistic) were previously servants. The cause of prostitution for these former servants is, the writer argues, ‘pride, and a desire of appearing out of their proper sphere’ (LM XVI [February 1785]: 96). Indeed, one of the most vexatious consequences of dressing beyond one’s rank is not a life of prostution (and consequently degradation, disease, squalor, unwanted pregnancy and early death): no, this writer finds the real disastrous effect is that it is no longer  ‘possible to judge people’s rank by their exterior; but now all propriety is banished, and one is momentarily in danger of mistaking a modern mop-squeezer for a capital tradesman’s wife’ (LM XVI [February 1785]: 27).

‘possible to judge people’s rank by their exterior; but now all propriety is banished, and one is momentarily in danger of mistaking a modern mop-squeezer for a capital tradesman’s wife’ (LM XVI [February 1785]: 27).

The serial continues with anecdotes and purportedly true stories for another two installments and is ultimately signed by ‘Annabella Evergreen’. It continues to blame servant girls for almost every ill known to humanity, including their own seductions by honest and innocent sons of the families for which they work. The rhetoric is fascinating and I highly recommend it. But what’s so interesting about its location in the magazine and its pointed nod to the Matron is that this opinion piece that masquerades as a moral essay would likely not have pleased the Matron, who offers a much more moderate view and is very empathetic to the plight of the less fortunate.

The genre of the miscellany necessitates that there is always a vexed relationship between how the various genres represent discourses, almost regardless of topic. Yet by probing these distinct treatments, it is possible to see that the magazine, while in one instance seemingly

reactionary and in the next radical, tends to offer an overall liberal treatment of the social issues that were of such interest to its readership. What makes it so fruitful to look at one topic across a range of genres within a given year, or within a given genre across a range of years, is that the variety and shifts in opinions and view represented within the periodical are given their voice again. The magazine’s multiple dialogues — between the genres as well as between the contributors to the different genres and columns — requires reading these conversations and their engagement with the contemporary social and cultural concerns in order to understand the otherwise seemingly disjointed and competing discourses.

Jenny DiPlacidi

University of Kent