Who or what makes meaning in magazines? Publishers? Editors? Advertisers (usually, in fact, these were the publishers or editors in the era I spend my working life in)? The authors of individual contributions? Or maybe even readers?

The answer, it seems to me, is never a clear cut one. The inherentally dialogic and dynamic format of the magazine means that it cannot ever be so.

The Lady’s Magazine is no exception. Individual contributors to the magazine often had very strident views on the topics about which they wrote, whether that topic was whether men were women’s intellectual superiors, the need to abolish the slave trade, or the best cure for unwanted female hair growth. But as we have indicated many times on the blog before – usually with a mixture of frustration and admiration – it is hard to identify any coherent editorial line running through the magazine at all. Nothing in the magazine is so consistent as its inconsistency.

It would be easy to offer ready answers to the question of why this is the case. These range from the uncharitable and surely untrue – the magazine was so shambolic that it didn’t know what it was doing – to the downright cynical and misleading – the Lady’s was so keen to secure as sizeable a readership as possible that it tried to be all things to all people. The more accurate answer still lies partly out of reach of my outstretched fingertips and would certainly take more words than I have here to try to work through. But any response to the question surely has to take into account one of the most important generators of meaning in the (indeed, any) magazine: the placement of contributions.

The implications of how articles speak to and against one another were something I spent a lot of time thinking about (again) in a recent talk I gave at the wonderful Disseminating Dress conference I attended at the University of York last month. This three-day conference organised by Serena Dyer (University of Warwick), Jade Halbert (University of Glasgow) and Sophie Littlewood (University of York) brought together academics, curators and practitioners to examine how sartorial ideas and knowledge were transmitted between individuals and communities from the medieval period to the present. I was delighted to be asked to speak about what the Lady’s Magazine had to say about dress and fashion.

Of course, the magazine has rather a lot to say and in lots of different genres, from antiquarian and anthropological accounts, to moral essays and advice columns on dress, to embroidery patterns and fashion plates. But perhaps inevitably, my talk ended up being less about what individual contributions or even distinct sartorial genres disseminated about dress than about how these different contributions and genres buffetted against one another to create meanings that were much more than the sum of the magazine’s individual parts.

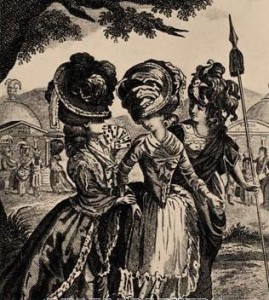

LM XXIV (May 1783): 267. Image © Adam Matthew Digital / Birmingham Central Library. Not to be reproduced without permission.

Take, for instance, this juxtaposition in the May 1783 issue. A month before, the magazine’s agony aunt, the Matron, had received a letter from a correspondent who went by the initials W. G., and who had complained bitterly about the unbecomingly masculine appearance of women who sported riding habits. The animosity behind W. G.’s attack is quickly diffused by the eminently sensible Matron who urges that ‘single ladies, if they find the riding habit more compact and convenient’ should be allowed to wear it ‘uncensured and unmolested’ even if she ultimately had to concede that married women, ‘if they are truly wise’, will ‘wear only those dresses which are most becoming in the eyes of their husbands’ (267). After a brief diversion on the ridiculous revival of the fashion for feathered garments, the Matron signs off by noting that ‘Moderation […] in dress as well as in diversions, is not only most convenient, it is also most becoming.’ With this, the Matron steers her usual, pragmatic course: misogyny is checked while propriety is observed.

LM XXIV (May 1783): 268. Image © Adam Matthew Digital / Birmingham Central Library. Not to be reproduced without permission.

But just when the magazine’s sartorial conservatism seems at its most surefooted, it is immediately undermined by the fashion report that follows it. Authored by an anonymous ‘Lady of Fashion’, one of a succession of early fashion journalists who graced the magazine’s pages, the report describes the latest fashions as popularized by the poet, actress (later novelist) and renowned celebrity Mary (Perdita) Robinson. The moderation called for by the Matron is flagrantly thrown off in the report in favour of sumptuous descriptions of the Rutland gown with its petticoats ‘tied back at the sides in the form of a Sultana’s robe’, the ’ made of silver or gold muslin and lined with coloured Persian’, as well as the ‘, trimmed with a wreath of white roses, and a panache of [the] white feathers’ the Matron despised, before closing with a reference to ‘Riding habits’, which are ‘much worn in the morning; the most fashionable are the Perdita’s pearl colour’ (268).

Whether the juxtaposition of the Matron’s column and the fashion report was a coincidence or manufactured is a puzzle that I suspect we will never solve. In a sense, though, it matters little. For this is no isolated incident and what is important about it is the range of effects the placement of such material had on readers’ experience of navigating the magazine’s content. And what is true for fashion is also true for the magazine’s conversations about marriage, class, domestic and global politics, the literary marketplace or any of the myriad subjects to which it returns. Few of these debates are ever definitively won or done with.

It would, I think, be all too easy to read these tensions as symptomatic of the mixed messages and impossibly contradictory feminine ideal that we have come to associate with the modern women’s magazine. But such views do not do justice to the complexity of the Lady’s. More to the point, they fail to acknowledge the form of the publication itself and the kinds of active reading practices it encouraged and which our blog and project as a whole seek to illuminate.

Readers of the Lady’s Magazine were far from passive. So many of the magazine’s most conservative pronouncements were actively challenged by editorial placement against articles or artifacts presenting contradictory points of view or by reader responses published in subsequent issues. The very form of the magazine – one in which every reader was a potential contributor and no one, not even respected authorities such as the Matron, could be guaranteed the final word on any subject – meant that every pronouncement it made in its pages was provisional and open to challenge.

The Lady’s Magazine’s driving principle, as we have alluded to before, was ‘conversation’, that ‘sieve that strains our thoughts of all their dross,’ as it put it in its March 1773 issue, ‘and like fire to gold, […] purifies the grosser and more unpolished ideas of our minds; it burnishes our mental magazine, and makes it fit for use’ (127). This is not to say that the magazine was entirely democratic or that some voices weren’t louder than others, but within the magazine’s community, dissent was encouraged and debate flourished.

Whether editorial placement was dictated by design or simply a happy accident matters little. Except to say, that the space that such placements opened up for readers to navigate the magazine’s content, to reflect on its import, to craft their own response, and perhaps to choose to share that response within the magazine’s pages, was surely one of the magazine’s greatest achievements and sources of its success.

Dr Jennie Batchelor

School of English

University of Kent

That’s so interesting. Thank you for sharing it. Very impressive article.

By making use of this support, you possibly can successfully make your web site significantly more interactive and social. The support of Blog site comments is hottest service that provide again hyperlinks on your own weblog. The support features two chief plans that include prompt site visitors likewise as a lot of back links. You also ought to consider treatment on the good quality which is certainly more chosen than amount in the time of submitting responses.