The moral tales in the Lady’s Magazine form a distinct genre that consists of short, often illustrated, didactic stories intended to convey a lesson or moral to the reader. One might imagine that such a genre communicates a consistent or coherent ideology, but the fictional content of the moral tale varies widely in both instructive message and writing style – even in works by the same author.

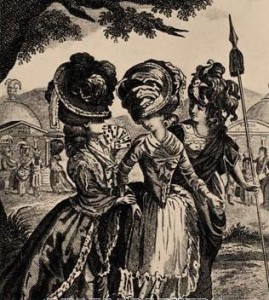

LM XXII (March 1781): 117. Image © Adam Matthew Digital / Birmingham Central Library. Not to be reproduced without permission

The prolific correspondent ‘R—.’ contributed moral tales for well over a decade, penning stories such as ‘Surgi, or the Stoic’ (LM IV [April 1773]: 193), ‘The Unexpected Meeting’ (LM IV [May 1773]: 233) – which takes place in Margate –, ‘Alphonso; or the Cruel Husband’ (LM V [April 1774]: 183), ‘Celadon and Florella; or the Perils of a Tete-a-tete’ (LM V [February 1773]: 65), ‘Penelope, or Matrimonial Constancy’ (LM V [September 1774]: 457) and ‘The Unwary Sleeper’ (LM V [May 1774]: 233). All of these tales have accompanying engravings and ‘R—.’ also contributed essays, opinion pieces, and serial fiction.

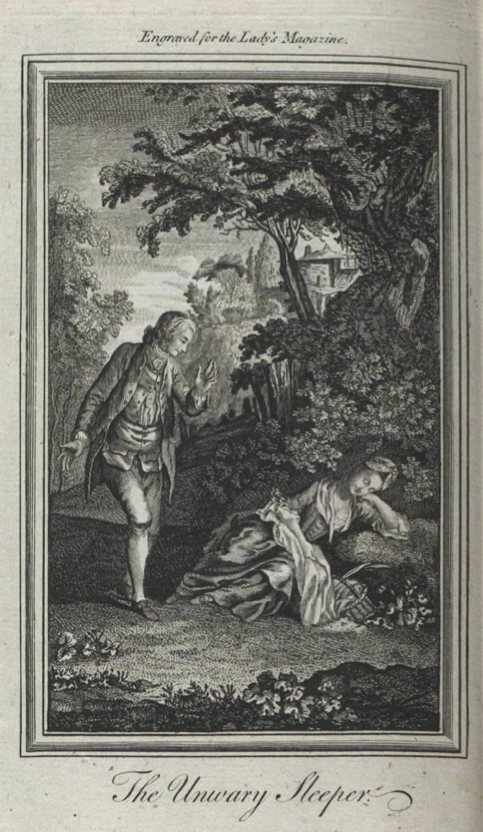

LM V (May 1774): 233. Image © Adam Matthew Digital / Birmingham Central Library. Not to be reproduced without permission

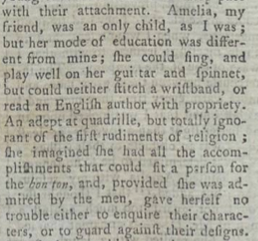

Because I would like to spend further time on this topic in future blog posts, I will only discuss two of the tales here. ‘The Unwary Sleeper’ and ‘The Fatal Wreath’ (LM XII [March 1781]: 117). In ‘The Unwary Sleeper’ the female character, Dulcetta, describes herself thusly: ‘My figure gave pleasure, but the readiness with which I imbibed the instructions of my teachers, recommended me more strongly than my personal accomplishments’ (233). In contrast, her friend Amelia’s : ‘mode of education was different from mine; she could sing, and play well on her guitar and spinet, but could neither stitch a wristband, or read an English author with propriety. An adept at quadrille, but totally ignorant of the first rudiments of religion’ (233), Amelia allows ‘liberties’ from men that shock her friend. After she elopes with Mr. D— it is revealed he is already married with ‘a family of half a score children’ (234).

LM V (May 1774): 233. Image © Adam Matthew Digital / Birmingham Central Library. Not to be reproduced without permission

Dulcetta’s religious and moral education has saved her from her friend’s fate, but the tale doesn’t conclude here, as it easily could. Instead, it transports Dulcetta one month forward to her father’s house three miles away. After this apparently insignificant alteration in time and location, Dulcetta feels removed from normality, a distance likewise experienced by the reader due to a shift from the earlier, matter-of-fact narration to a tone similar to a fairytale. The estate, ‘in the midst of a wood, and [. . . ] entirely by itself’ affords her no companion and so she wanders alone, picking wildflowers and reading. Laying down under a large tree, she is ‘immediately transported into the land of dreams. I thought that I was in a solitary place, and that a person was attempting to be rude with me. I shrieked—the shriek waked me—and who should stand before me but the treacherous Mr. D—,’ (234). Dulcetta is saved by one of her father’s servants and the incident causes her to conclude that ‘the fall of the sex is generally owing to their vigilance’s being asleep when it should be awake’ (234).

The pointed observation feels ill-suited to the preceding passage given that the moral female protagonist was sleeping when attacked and only fortuitously saved by an improbably located servant. If even a virtuous and properly educated female risks a ‘fall’ by falling asleep, R—. seems to suggest luck, more than vigilance, is needed to save one’s virtue.

LM XXII (March 1781): 117. Image © Adam Matthew Digital / Birmingham Central Library. Not to be reproduced without permission

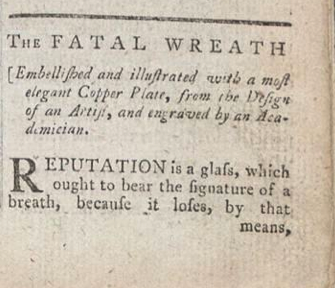

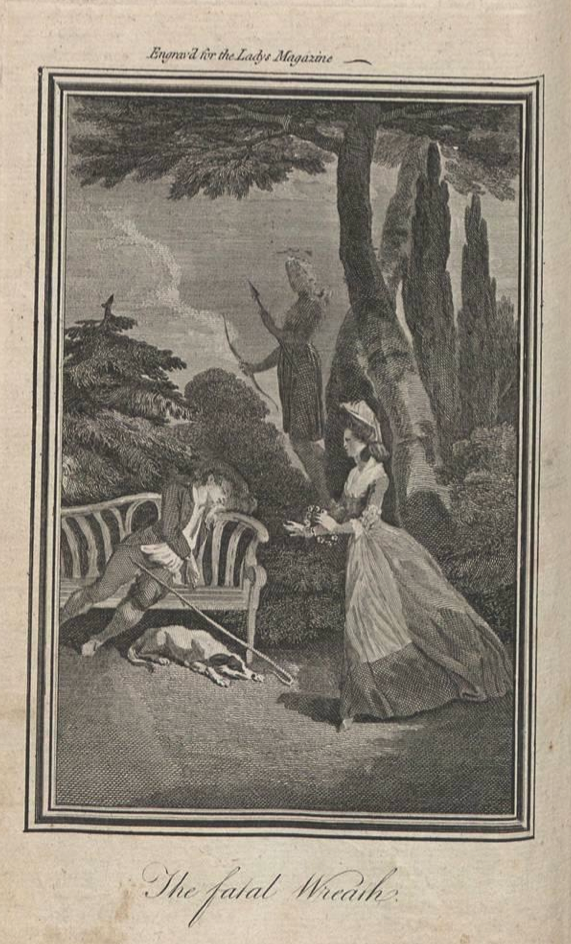

R—.’s March 1781 tale ‘The Fatal Wreath’ features another slumbering character, but this time the sleeper is the (would-be) seducer of the luckless Almira. Celadon, ‘fond of dissipation’, persuades Almira into frequent meetings in a grove decorated with a statue of Diana, goddess of chastity, where Almira makes ‘concessions [. . .] which she wished that she had not made’ (118). When she finds him asleep in the grove one summer’s evening, she places chaplet of flowers on his head. Suddenly fearing the statue of Diana is animated, ‘that she even pointed her shaft against her’, Almira flees, but ‘a viper bit her heel – she sunk – she died – she might have met with a worse, had Celadon awoke, when she placed the flowery wreath on his temples.—Let the sex beware of innocent advances and liberties; advances and liberties are dangerous’ (118).

LM XXII (March 1781): 117. Image © Adam Matthew Digital / Birmingham Central Library. Not to be reproduced without permission

Again, the moral is intriguingly elusive. R—. states that ‘advances and liberties are dangerous’ but it is unclear just how far the liberties between Celadon and Almira have gone. By suggesting that had Celadon awoken Almira would have met with a fate worse than death, R—. implies that she has not already had sexual intercourse with Celadon in spite of allowing some ‘concessions’. The viper bite saves Almira from what might have been, rather than punishing her for what has already occurred. The ‘what might have been’ fate could also have befallen the virtuous Dulcetta in the ‘The Unwary Sleeper’ yet she was saved by luck. Regardless of the potential danger of liberties, advances, and slumber, what R—. depicts as the actual, physical dangers to unwary or unguarded women are vipers and, of course, treacherous men.

Dr Jenny DiPlacidi

University of Kent