Working on The Lady’s Magazine can be a pretty heady experience. Take one magazine that ran for 13 issues a year for over six decades. Add a generous dose of content representing pretty much every single prose, poetic and dramatic genre you have ever heard of (and some you don’t like to admit you haven’t). Finish with the zest of a sprightly community of readers, almost none of whom used their own names within the magazine’s pages. The result: one dizzying cocktail that brightens up your day right up until the moment when the room starts spinning before your very eyes.

Today, after my latest binge on the magazine in preparation for two still not-yet finished papers I’m giving in quick succession next month, I feel it’s time to confess my sins.

My name is Jennie Batchelor. And I am a periodicalist. I sometimes say one thing and think another. I am beyond help. In fairness, though, it’s not really my fault. I mean, I know that old saying about workmen and their tools, but have you seen what I have to work with? I mean, come on!

LM, XV (Oct 1784): 547. Image © Adam Matthew Digital / Birmingham Central Library. Not to be reproduced without permission.

But I digress… This is how it happened. A couple of weeks ago I was sat at my desk having read through a big stack of interesting journal articles, chapters and monographs on anonymity and pseudonymity from the Early Modern period to the present. The goal was to contextualise and theorise my reading of the practice of pseudonymity in the Lady’s Magazine for a paper I am giving at an eighteenth-century studies conference in the US on a panel on the study of women’s writing now that we are in a ‘post-recovery’ moment. The abstract, which I sent off last year, promised to develop an argument that I had begun to sketch elsewhere: that anonymity and pseudonymity pose huge challenges not just to literary scholars but to feminist or women’s writing academics, in particular, and that we need to embrace these challenges enthusiastically. I maintained that the many hundreds of unknown women – the Constantia Marias and Lucindas – who wrote for the Lady’s Magazine and possibly had no more lofty career aspirations than publication within the periodical’s pages demand to be understood as an important part of women’s literary history, even if all we know about them are the presumably mostly false names they adopted.

As Virginia Wolf pointed out ‘Anon’ was all too often a woman. Of course, sometimes she was a man, too. And as the Lady’s Magazine suggests with dizzying frequency, sometimes she was a woman pretending to be a man, or man pretending to be a woman. Its readers commonly wrote in when articles by ‘A SPINSTER’ seemed more likely to have emerged from the pen of the most curmudgeonly of bachelors, or when the spirited defences of the fair sex by male wits seemed to speak more of insider knowledge than of chivalry. Nonetheless, as I contended in my abstract for the conference, I wanted to argue for the importance of the magazine in the history of women’s writing, even if some of its women were pretending to be or actually were men. The identities of individual authors interested me much less than their collective endeavours in the creation of a mixed-sex, but female dominated, dynamic writerly community which was not in the least hung up on the Romantic conception of the author as solitary genius and which set the agenda for the public discussion of women’s lives across the decades in which it thrived. (That’s the short and slightly simplified version, anyway.)

LM, XXXIV (May 1803): 252. © Adam Matthew Digital / British Library. Not to be reproduced without permission.

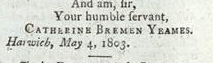

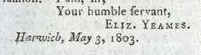

Yet for all my anti-Romanticist impulses (I told you this was confessional, didn’t I?), I still managed to spend about 6 hours on the day I had marked down in my diary as ‘anon research day’ trying to track down the identity of two women who I have become completely absorbed by in the past few months: Catherine Bremen Yeames and Elizabeth Yeames (although every single one of their Christian and surnames is spelled or abbreviated in multiple ways in the magazine’s pages). They started writing for the Lady’s in the 1800s and as I was re-reading the issues from those years, I became intrigued by their many, varied and distinctive contributions, just as I was tantalised by the fact that they shared a name and both resided in Norfolk, which seemed to indicate that they were related to one another.

Who am I kidding? I also was gripped by the thought that they had to be traceable given that they had such an unusual surname, untypically given in full in the magazine, and that they were tied to a specific locale. If I couldn’t find these women then I may as well give up the attribution ghost entirely.

LM, XXXIV (May 1803): 253. © Adam Matthew Digital / British Library. Not to be reproduced without permission.

Needless to say, I found them. A typo I made in the last Google search I was going to allow myself of the day set me on a chain of web searching that led me to the baptismal records of the sisters (because they were sisters after all), details of their parents’ names and wedding date (not in Norfolk, but rather pleasingly for this project, just a few miles from my University in Dover) and the birth and christening dates of their many other siblings.

I became lost in the websites complied by resourceful and generous family genealogists, who with little interest in the sisters nonetheless gave off hints of important information that led me to understand that Catherine’s contributions to the magazine stopped because of her premature death as a young woman (the family trees I had seen her mentioned in wrongly assumed she died at birth), while her younger sister Elizabeth continued to write for the periodical for many years afterwards and looked expressly to it for help to support her family after the death of her oldest sister and her naval father overseas. Three months after this appeal, Elizabeth married, I discovered, and regardless of whether this helped her financial situation, she continued to write for the Lady’s under her married name (the connection to her unmarried self is not openly acknowledged in the magazine’s pages and would have been known to me had I not made the connection this way). It was a fascinating journey that took me to the will of the sister’s mother (unbelievably available online) and to Elizabeth’s own resting place, in a grave with her mother and another of her sisters. I even managed to get a photograph of her tombstone emailed to me later that day through another website for genealogists.

There is a lot more to tell about the Yeames sisters and a good deal more to say about their writing. I’m not done with them, that’s for sure. So watch this space, as they say. Yet I confess, that on my ‘anon research day’ I felt bad rather than amused by the irony that I spent so much time obsessively trying to find out exactly who two women periodical contributors were that I forgot to eat lunch and only remembered to pick up my kids with five minutes to spare.

But this is what working with periodicals like the Lady’s Magazine is all about, isn’t it? You see, here’s my big confession. I like working with periodicals because they are so infuriating. I like them because every time I think I may be starting to understand what they are about they wrong-foot me and suggestion other, equally plausible, possibilities.

I really don’t believe that our research project needs to attribute huge swathes of articles to known or important writers to put the Lady’s Magazine on the academic map. Even to attempt to do so would, as I’ve already hinted, be rather at odds with what I think the magazine was about and trying to do. Nor do I believe any less in the importance of pseudonymity to the magazine or to the history of women’s writing for all my determination to seek out the identities of some magazine contributors.

I like historic periodicals and I believe that many of them are deeply important because they keep me people like me on toes by forcing me to question my and ‘the disipline’s’ logic and familiar crutches – of genre, gender, politics, period, and ‘the author’ – at every turn. Ephemera indeed!

Dr Jennie Batchelor

University of Kent

Dear Eleanor. Thanks so much for your comment and apologies for the belated reply. We’ve had problems with the blog that prevented us logging in for several days. We’re all very interested in thinking through the parallels between the culture of pseudonymity and anonymity in the blogosphere today and back in the Lady’s Magazine. Of course, you are right that what pseudonymity means in general in any given period is historically specific to a degree and things just were very different in the later eighteenth century. For one thing, anonymity was the norm, rather than the rule in publishing at the time. There has been some fascinating research done by James Raven on the novel in this period that categorically proves that the vast majority of new novels published in that period were anonymous (and that is men and women publishing anonymously). That said, you are absolutely right, I think that personal fame for women without wealth then could be risky and surely isn’t only to those who enjoy privileges of sex, wealth or class. The recent case of various drag queens taking on Facebook, who took down accounts in their professional drag names because they were pseudonymous, springs to mind here. I (Jennie) gave a paper on anonymity and pseudonymity at a conference recently and am writing a chapter for a book on it in the coming months. More to follow on the blog. Thanks again for commenting!

I’m curious to hear whatever you have to say on pseudonymity in women’s writing. I have published a pseudonymous blog since 2007, and although it is fairly easy for anyone who wants to, to find out who I am – either by asking around in the relevant community, by doing a little detective work, or indeed by asking me – I have nevertheless kept it pseudonymous. This preserves the brand, but it also means sacrificing the promotional opportunities of Facebook and G+, and working around their real-name policies. So I am deliberately much less well known than I could be. My reasons for this are complex but probably have a lot in common with the contributors to the Lady’s Magazine. Specifically, as a woman I feel that personal fame without wealth is more immediately risky than possibly advantageous. I think real-name policies obviously come from a position of male privilege (not having to worry about stalking, harassment, etc). But it’s surely a little more complex than that.

Pingback: Periodical Confessions | To Be An Electric Telegraph