This 2nd century Roman mosaic from Tunisia is a fine example of its genre and interesting for its depiction of lions, a not unfamiliar scene in artwork of the era.

The picture manages to look both familiar and unfamiliar at the same time. Two lions devouring prey, yet it is two male lions. The prey is relatively large compared to the lions but it is only a pig. The scene is a dry and sparse climate and there are depictions of human presence a temple or palace perhaps… all somewhat fanciful, surely?

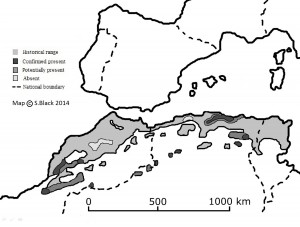

There are many pre-Roman artistic depictions of lions devouring prey in Mediterranean art (bulls, deer etc.). Perhaps fewer of lions eating wild boar. We do know that wild boar are the prey of lions in India today and boar would have been prey elsewhere in the former middle eastern range of the species. They would also have been a key prey for lions in North Africa as depicted in the mosaic. If lions were still present in the wilds of Algeria or Morocco today, then wild boar would probably be the best food source (other than domestic flocks).

We know that Barbary lions tended to operate in small family groups rather than the prides familiar in savannah landscapes, so it is interesting to see two males in this depiction – does this offer a clue to how Barbary lions behaved, perhaps?

In reality almost all lion depictions of the classical era show male lions and almost never lionesses, so little can be gained from this depiction. The Tunisian mosaic is most probably a purely artistic interpretation of events. It is satisifying, however, to see the lions depicted with a known wild prey species form the region. In classical European artwork lion prey is more often depicted as domestic cattle, donkeys, horses or wild deer. Interestingly 18th and 19th century art often depicts lions attacking horses and domestic camels.

Further Reading

Black SA, Fellous A, Yamaguchi N, Roberts DL (2013) Examining the Extinction of the Barbary Lion and Its Implications for Felid Conservation. PLoS ONE 8(4): e60174. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0060174

Yamaguchi N, Haddane B. 2002. The North African Barbary lion and the Atlas Lion Project. International Zoo News 49 (321): 465-481.

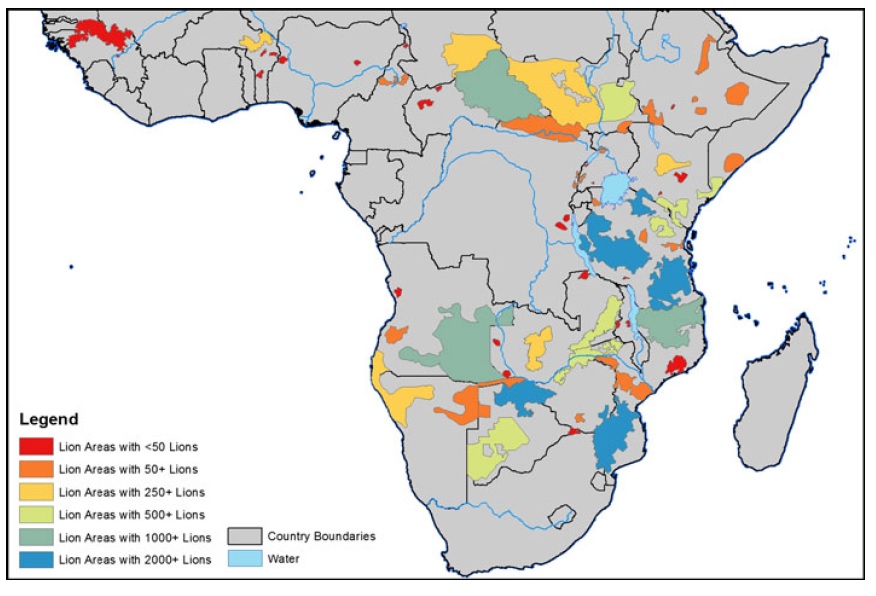

![North Africa's historical biodiversity is compatible with India temperate regions - even elephant existed in the Maghreb until historical times. Modern India is justifiably proud of its biodiversity heritage [Map adapted with North African additions from concept by Karanth (2014) photos: K. Varma, N. Mehta, S. Mahanta, H.S. Singh, H. Malik].](http://blogs.kent.ac.uk/barbarylion/files/2015/01/India-and-North-Africa-Fauna-enhanced-1024x711.jpg)