Simon Black –

I am involved in a lot of work with assertive behaviour training, coaching and support for conservation professionals working in the field, in office bureaucracies, in laboratories and in zoos.

The basic mindset of an assertive leader is to think win-win – to keep a strong value for yourself and your needs, but also be mindful and work with the needs of others. if you simply ride roughshod over other people’s interests you will destroy trust and erode support. remember compliance in not the same as commitment. A leader who thinks that a team simply ‘doing what it is told’ is performing at its peak is deluding themselves.

Win-win (Covey 1987) means looking to strongly but fairly assert what is needed to enable the project to succeed – to keep tasks on track and accurate, to keep the team dynamics effective, and to keep individuals developing and performing to potential. of course in the real world many things can compromise this success – money , resources, climate, luck. what you do not need is for manageable things – like your own behaviour as a leader, or the behaviour of others in the team, to get in the way on top of this.

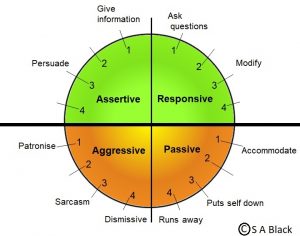

The model which I introduce to people in training and coaching sessions follows four segments of behaviour: Effective Assertive/Responsive behaviours and Self-Defeating Aggressive/Passive behaviours.

Assertiveness (Smith, 1975) enables you to access a range of behaviours in the green win/win areas of behaviour to influence others (Coppin and Barratt, 2002). You can show low level assertion by simply giving clear information or instructions. You can you higher level of assertion by giving reasons.

The skills can be learned and practiced.

The trick is to avoid the Aggressive and Passive behaviours yourself and in your team’s behaviour. This will not be achieved 100%, but aim to operate in the Assertive/Responsive boxes most of the time. I describe these effective win/win behaviours as “Above the Line Behaviour”.

Assertive behaviour is consistent with systems thinking. It gives colleagues clear inputs and feedback to allow them to make decisions about how to operate. If we have clear values that are consistent with the purpose of our team and a win/win mentality, we can use assertiveness to encourage people to work effectively with us and together with colleagues (Kouzes and Posner, 1995).

There is much to learn about interpersonal behaviour, and a huge amount to gain form new skills. it is not a matter of psycho-babble and game-playing. Quite the opposite. Assertiveness cuts through all the garbage.

References

Coppin, A. and Barratt, J (2002) Timeless management. Palgrave MacMillan, NY.

Covey, S. (1989) 7 Habits of Highly Effective People. Simon & Shuster, New York, NY.

Smith, M. (1975) When I say no I feel guilty. Bantam Press, New York, NY

Kouzes J.M. and Posner B.Z. (1995) The Leadership Challenge. Jossey-Bass, San Francisco, CA

Don’t rely on top down change; take a lead yourself and start small if necessary.

Don’t rely on top down change; take a lead yourself and start small if necessary.