Simon Black –

This week Carl Jones was awarded the 2016 Indianapolis Prize which was instigated in 2005 to celebrate the men and women who have made extraordinary contributions to the sustainability of wildlife.

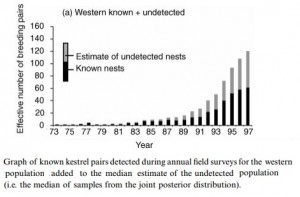

Carl, the Chief Scientist for Durrell Wildlife Conservation Trust and Scientific Director for the Mauritian Wildlife Foundation, received the award for his momentous victories saving species and restoring ecosystems. These are all well documented elsewhere (for example see the Durrell site), but in a nutshell, Carl’s achievements in saving bird, bat and reptile species on Mauritus and Rodrigues account for about 10% of all recovered species globally. His bird recoveries (Pink Pigeon, Mauritius Kestrel, Echo Parakeet, Rodrigues Fody and Rodrigues Warbler) account for 19% of all saved bird species.

For all of his accolades, Carl is most satisfied that, through the award, the importance of these less well-recognised species of Mauritius has been honored.

What is important in Carl’s work, aside from the fact that animals still exist in the Mascarene forests today which would otherwise be limited to a few dusty museum skins, is that he has pioneered a method. Species conservation is about doing it not just talking about it. Hands-on skills are vital, as is a commitment to short-term goals, but always with a long term vision of what could be achieved.

For Carl, leadership is not about the leader, but about leading others in the work, and enabling them to take up the mantle, to apply and further develop skills and techniques. Hundreds of people have been ‘apprentices’ in Mauritius and now work all over the globe directly influenced and taught by Carl. His is a great example of distributed leadership.

It is a pleasure to work with Carl, picking out the do’s and don’ts of conservation management. It was fantastic to see his career of over 40 years recognised for its outstanding achievements. Long may his influence continue to enable the recovery and sustainability of wildlife on the planet.

Black, S.A. (2016) How the last two Montserrat ‘mountain chicken’ frogs could save their species. The Conversation https://theconversation.com/how-the-last-two-montserrat-mountain-chicken-frogs-could-save-their-species-58681

Carl Jones, who has led the Mauritian programmes for over 30 years, was quick to enhance his own knowledge of kestrel breeding with techniques which had previously proven successful in efforts in New Zealand and the USA. He has used a better way. Instead of imposing a command-and-control structure on his teams, he has developed a ‘system’ and more importantly, he appears to be applying systems thinking in the way that he manages the team. Every part of the system; habitats, diet, supplementary feeding, breeding facilities, nest locations, monitoring, predator eradication, bird behaviour, technical skills, equipment.

Carl Jones, who has led the Mauritian programmes for over 30 years, was quick to enhance his own knowledge of kestrel breeding with techniques which had previously proven successful in efforts in New Zealand and the USA. He has used a better way. Instead of imposing a command-and-control structure on his teams, he has developed a ‘system’ and more importantly, he appears to be applying systems thinking in the way that he manages the team. Every part of the system; habitats, diet, supplementary feeding, breeding facilities, nest locations, monitoring, predator eradication, bird behaviour, technical skills, equipment.