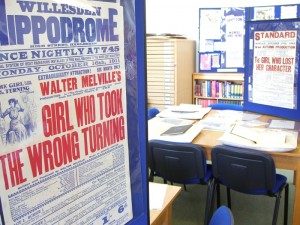

When you walk into an archive or library, it’s often much more exciting to find a variety of interesting and colourful materials laid out to look at than to enter a dull and stale space. Displaying Special Collections materials is one of the parts of my job which I enjoy the most; I’m lucky enough to do this several times a year for seminars and visits. Displays can celebrate a newly acquired collection, or the completion of a project, be used to show off some of the lesser known parts of a collection, or to pique interest and draw in people who might not otherwise think to look at the Collections. I find this especially satisfying because it allows us to delve into the lesser used materials in our store which deserve to be more widely studied: usually, being shown an object like this will encourage people to carry out their own research and discover the archive for themselves. From my experience as a researcher, I know how exciting this can be!

When you walk into an archive or library, it’s often much more exciting to find a variety of interesting and colourful materials laid out to look at than to enter a dull and stale space. Displaying Special Collections materials is one of the parts of my job which I enjoy the most; I’m lucky enough to do this several times a year for seminars and visits. Displays can celebrate a newly acquired collection, or the completion of a project, be used to show off some of the lesser known parts of a collection, or to pique interest and draw in people who might not otherwise think to look at the Collections. I find this especially satisfying because it allows us to delve into the lesser used materials in our store which deserve to be more widely studied: usually, being shown an object like this will encourage people to carry out their own research and discover the archive for themselves. From my experience as a researcher, I know how exciting this can be!

However, there is a major trade off in this method of drawing people’s interest and, having just been on an excellent course about the handling and display of rare books, it occurred to me that no-one in this sector has really come up with a satisfactory solution, yet.

The reality is that all books (even new ones) and archival objects are damaged by factors which are impossible to  remove in most normal workspaces. Light (daylight and electric), fluctuating temperatures and humidity, transport, dust and handling all play a part in slowly degrading a book over time. For preservation of books, the ideal would, I suspect, be to keep them in a climate controlled store, in the dark and fully sealed so that pests, mould and other external problems could not cause damage. Of course, in the real world, this isn’t possible: not least because the reason for having these books and items is help in research and learning. To be honest, it would be a waste to have a collection which was rarely seen or used, even if it was maintained in a perfect environment. Certainly in Special Collections, the materials need to be used and investigated to prove that they are worth having.

remove in most normal workspaces. Light (daylight and electric), fluctuating temperatures and humidity, transport, dust and handling all play a part in slowly degrading a book over time. For preservation of books, the ideal would, I suspect, be to keep them in a climate controlled store, in the dark and fully sealed so that pests, mould and other external problems could not cause damage. Of course, in the real world, this isn’t possible: not least because the reason for having these books and items is help in research and learning. To be honest, it would be a waste to have a collection which was rarely seen or used, even if it was maintained in a perfect environment. Certainly in Special Collections, the materials need to be used and investigated to prove that they are worth having.

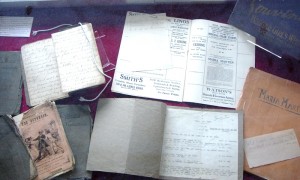

A major part of my work is focused on limiting the possible damages to collections. We store our materials in an environmentally controlled and locked store. The reading room is difficult to make an ideal space for the books, but we do have UV filters on the windows. Considering that most of the damage done to items is through use, we can limit this by putting items in protective covers, using copies and providing book supports. The ban on food, drink and pens in the reading room is to make sure that accidents don’t end up irrevocably damaging any of the materials. Our attitude towards copying, through scans or photocopies, is guided by the same principles. It’s worth noting as well that most archives or rare book collections no longer advocate the use of gloves because, among other reasons, wearing gloves makes it difficult to handle materials gently. It is much better for the materials that researchers have clean, dry and oil-free hands: the Natural History Museum has started issuing alcohol free hand wipes to all of their readers.

Displays can be difficult because I often have material that I would love to share but is just too fragile or delicate or bulky for an exhibition. This is where I really have to weigh up what can realistically be used. While using the originals is much more interesting, sometimes a copy is enough: if researchers are interested, they can then request the original to look at in a more controlled environment. If, as we hope, we are able to expand our displays beyond the reading room, this will require more careful thought and planning about how to minimise risks to materials and maximise the insight people can have into the collections.

Displays can be difficult because I often have material that I would love to share but is just too fragile or delicate or bulky for an exhibition. This is where I really have to weigh up what can realistically be used. While using the originals is much more interesting, sometimes a copy is enough: if researchers are interested, they can then request the original to look at in a more controlled environment. If, as we hope, we are able to expand our displays beyond the reading room, this will require more careful thought and planning about how to minimise risks to materials and maximise the insight people can have into the collections.

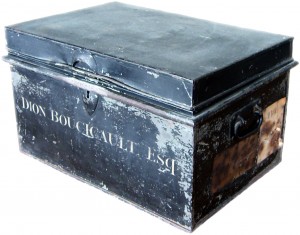

The materials in Special Collections were donated or bought on the understanding that they would be maintained and protected but at the same time made available to researchers in a way that has a real and useful impact on their research. This is our main aim in our work: a difficult balance which I spend most of my time trying to maintain. If we get it right, which I hope we do most of the time, the collections will be here to entrance and interest researchers for hundreds of years to come!