Although it was a little while ago now, I’d like to take the opportunity mention the exciting event which I was involved in a couple of weeks ago: a read through of one of the Melville melodramas.

If you’re a regular reader of the blog, you’ll probably have noticed how I keep talking about the Melvilles – a theatrical dynasty who reached the peak of their success around the turn of the nineteenth century through to the 1930s. Two of the Melville brothers, Walter and Fred, were immensely successful in running theatres and producing (and often writing) hugely popular plays. One of the genres they specialised in was melodrama, and they created their own niche in this type, with the ‘Bad Woman’ dramas.

As part of UoK’s Melodrama Research Group, I was asked to provide something for one of the evening discussion sessions; although the majority of the group are film specialists, this time we looked to the stage for inspiration, and decided to do a read-through of one of these once popular but now largely forgotten plays.

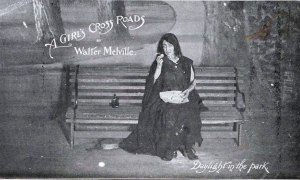

I chose ‘A Girl’s Cross Roads’ by Walter Melville as our piece, largely because it wasn’t too long (so it should fit into the two-hours allotted), and because we had already created a surrogate of the manuscript for teaching purposes (this means that we can provide access to the text without further damaging the original). The play was first performed in 1903, although we do not know where this performance too place. It has, as far as we know, never been published (like most of the other Melville plays in our collection) and has been subject to very little academic study. While I suspect that this play was revived later by the Melvilles, I felt privileged to know that this would probably be the first time the play had been read-through in around 100 years.

Publicity image from ‘Stageland’, September 1905 (0600336)

It’s a gripping plot, heavily reliant on past misunderstandings, mistakes made in life and no small amount of coincidence, but proved to be an exciting read. The story centres around Jack Livingstone, who has married and lives a comfortable life until his wife, Barbara, with secrets of her own, begins to suspect that he does not love her. Through a range of conversations at the beginning of the play, it transpires that Jack is not in love with Barbara after all, and now regrets not marrying his childhood sweetheart Constance. Of course, the plot does not stop there: the villains Cuthbert Lumley and Tilly Vane, the ‘bad woman’ of the piece, discover that Constance is ignorant of her inheritance and plot to steal it by marrying her to Cuthbert. With Barbara struggling to cope with the knowledge that her husband wishes he had never married her and past problems with alcohol, Tilly hopes that once Constance is married, she will be free to marry Jack herself.

Publicity image for the play from ‘Stageland’, September 1905 (0600336)

The play unfolds with surprising speed and with a significant amount of humour, not to mention a vast array of characters which our 7 strong cast managed by doubling and tripling up to cover all the parts! The read-through proved just how humourous the play was written to be, which is much clearer when reading it aloud in parts. Although there is a lot of slapstick which the small room and the limited acting experience of our group couldn’t quite do justice to, the script itself has some unexpected laugh-out-loud moments.

Most interesting to me, however, was that the play was not so stereotypical and one dimensional as the title (and stage melodrama’s posthumous reputation) led me to believe. Admittedly, there was little character development and little subtlety, but the plot was strong and the actors, particularly in the female roles, were given great opportunities to exercise their character talents. One character was developed throughout the play is that of Barbara (admirably played by Dr. Helen Brooks), who fluctuates between a victim of circumstance and of the hero, Jack, an obstacle to be overcome and a woman whose inability to maintain strict Edwardian control over herself led her to destruction.

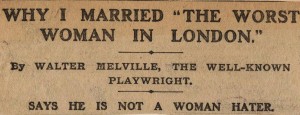

Far from being a moral diatribe on how women should behave, this play used the three female characters to explore very different choices made in life. These choices prove to be the girls’ cross-roads in life, although it’s never made clear to which girl the title refers. Tilly Vane in particular, the villainess, has several monologues in which she regrets her life and the outcast which her choices have made her. All three women find their lives shaped by men, whether or not they want to be, and this offers a rather more complex message than that of Walter Melville as a ‘woman hater’, as he was accused.

There’s more information and some discussion about the read through on the Melodrama Research Group’s blog, and we do hope to have some more read-throughs in the future, now that we’ve been well and truly bitten by the Melville bug. It just goes to show that, even after 110 years, the Bad Woman dramas can still intrigue and entertain us, as they were written to do.