I hesitate at gurning maw of the industrial paper compacter, suffering an existential crisis.

I’m at the council tip, clearing out my children’s school exercise books. There’s too many of them and they are cluttering up the house.

I’m at the other end of the historian’s telescope; I’m making decisions about archiving—or not. And it’s doing my head in.

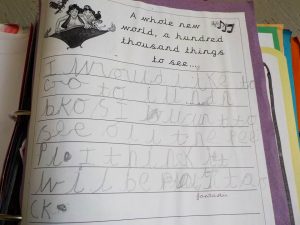

So many hours of work, from three small hands (two left, one right), are archived in these A4, paper-bound volumes. The maths is formulaic enough—lists of near-identical sums and times-tables—but there are also poems, stories, fragments of childish insight upon the world. I am throwing away my children’s labours. I am throwing away my children’s thoughts.

I am throwing away my children.

No, I correct myself: I am throwing away the fantasy that my children can be frozen in time, and the relinquishment of that fantasy is to the good. A fond memory is a dangerous thing; it takes up house-room that is needed for present realities. What kind of parent wants to preserve their child as an innocent five-year-old? What kind of innocence would that be?

Besides, if I keep the books, when will I look at them? When the children have left home? When I am old? Intolerable thought: it entails that I am facing death. Will I want to look at them if one of the children has died? Not merely intolerable: this thought is unthinkable. If I keep the book, I think superstitiously, I plan for the event.

Then I catch the snag in this train of thought: I am presuming the books are mine. Ah, but if I ask the children, they will certainly want to keep them. They want to keep everything: bus tickets, a sticky animal card from a box of sweets, a bit of hubcap they found on the roadside. So I must decide on behalf of their future selves. If I keep the children’s books, will they want them? Do I regret the fact that I have no examples of my own school work? Not in the least.

But suppose one of the children becomes famous, perhaps a novelist? Literature scholars will curse the fact that they have no insight into his earliest writing.

I reprimand myself for my vicariously hubristic fantasy. Then I think, hell, someone has to become a famous writer, and there’s no reason why it might not be one of them.

Who aspires to be a historical character? Surely only the self-entitled and the deluded. If only the self-entitled retain their records, then they manoeuvre themselves into their own historical afterlife. Perhaps their future history, proleptically enacted in the act of archiving, even makes their life ‘successful’. The act of archiving shapes the present in deeply conservative ways, re-engraving the same lines of historiography over and over again. The archive is destiny.

However, it is no hubris at all to assume that the children will be part of some collective historical story whose outlines I cannot yet discern. Who am I to say what sources will speak to that story? Perhaps I owe it to historians to keep my children’s material precisely because I believe they are ordinary, to dilute the archiving of the expected.

So far as the individual concerned goes, being destined for success—for a particular kind of success, as a writer, say—might be regarded as a blessing or a curse. By throwing away I keep my children’s choices open even as I hide them from the historical lens of success. I gain my children mental health, but I remain conservatively passive with regard to the shape of future history.

I console myself further with the professional thought that juvenilia reveals little: that psychologising of the infant subject is an unproductive research method.

And yet…

My current research concerns a set of historical ‘nobodies’, a group of young science fiction fans in inter-war Britain. Their very non-importance to history is what makes them interesting to me—they offer a precious clue into what (some) ordinary people thought about science: how they interacted with it. They have not left much by way of historical traces; even their census records from the period have been lost by fire. Their youthful enthusiasm is ephemeral, caught in a moment of hope before the Second World War, and all the more historically precious for it. I would be cock-a-hoop if I stumbled upon their school-books.

And now I am making life difficult for future historians in exactly the same way.

I am a thrower-away of my own potential archives. I can’t bear the thought of people reading my letters, my drafts, my notes. I can safely assume that I won’t be famous enough to cause a biographer to curse; but I am a part of stories that might be of future interest—gender stories, stories about higher education, stories about science and society. Do I have the right to deny future historians their sources? Do I have a right to disinter the sources of others?

I can’t help but notice that many of my historian colleagues talk about ‘The Archive’. Is it mere chance that this strange singularity institutionalises the life of sources, removing them from their originators’ choices about saving or discarding?

Should a historian think more about her afterlife as a historical subject, and if so, how would this change her historiographical practice?

*

I didn’t have time to think about all this too much, at least, not whilst I was facing the compactor. I had to hurry away; my eldest son was in the car, a doctor’s appointment due in ten minutes’ time. He had a bacterial infection—no big deal: the antibiotics he was prescribed are currently clearing it up nicely. A hundred years ago, he might have died from it. I know that from history.

Recent Comments