For Lucius and his family — just like for most Romans — a trip to the baths was an essential feature of every day life. By the first century CE, just about every town across the Empire took part in this practice. But the baths were not only about keeping clean, the practice of communal bathing also offered the chance to socialise and even get invites to dinner.

The changing face of public baths

As the practice of public bathing expanded, the bath complexes evolved into spectacular and sophisticated examples of Roman architecture. Early public baths were dark and steamy, but that began to change around the first century CE, as the newly perfected production of window glass allowed for a much lighter and airier environment. The improvements didn’t always find favour, however. In Letter 86, Seneca writes in support of the old-style baths buried in darkness at the villa of Scipio Africanus, contrasting the experience with the needless extravagance of the newer facilities. Seneca vividly describes how the new luxurious establishments are richly decorated with large and costly mirrors, imported marble, and have water pouring from silver spigots.

Seneca may not have been a big fan of the new style bathhouses, but others clearly were. Martial, for example, sings their praises — note how even the quality of water is exalted. Mart. 6.42 (link here)

However, some commentators paint a rather different picture. Marcus Aurelius, for example, talks of the oil, sweat, dirt, and filthy water at the baths. Med. 8.24. Celsus also casts aspersions on the water quality of the baths, as he warns that the worst thing for a fresh wound is a trip to the baths, as it can result in a wound becoming gangrenous. Celsus 5.26.

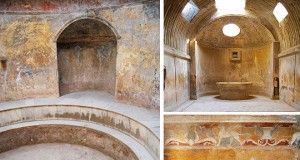

The Forum Baths at Pompeii give us an idea of the type of architecture and decoration lavished on the bathhouses. Left, the frigidarium (cold room), top right, the caldarium (hot room), bottom right, detail of decoration in the apodyterium (changing room). Images: Paula Lock

In the film, Lucius visits the Baths of Agrippa, located in the southern part of the Campus Martius. These baths were the first of the great Imperial Thermae.

Although today not much is left of the complex, the baths at Pompeii (Central Baths, Forum baths and the older Stabian Baths) can give us a good idea of the type of experience Lucius might have had on his visit.

Plan of the Baths of Agrippa (Plan by Inga Friis from Nielsen 1990, fig. 49).

A trip to the baths

The time you chose to visit the baths played a key role in shaping your experience, as the temperature varied throughout the day. In the film, Lucius visits the baths at the 8th hour (2pm) when they were at a ‘perfect’ temperature (this is the hour recommended by Martial 10.48). Two hours earlier, they would have been at their hottest and as the sun began to set, they became tepid. The rich, who had no time constraints, could choose to bathe at the optimum time and therefore temperature, but labourers or slaves — who were not in control of their time — had to settle for a tepid bathing experience once their work was done.

On entering the baths your first stop would be the apodyterium (changing room). Here you removed all of your clothes. The only thing you would keep on would be your bath sandals, which helped to protect your feet from the heat of the floors.

The apodyterium (changing room) in the Central Baths at Herculaneum. Image: Paula Lock

Some Romans took a clothes guard along to the baths with them — for example, Martial mentions Aper who employed a one-eyed woman to watch over his belongings. (Mart. 12.70.2) If you didn’t have a clothes guard, you could find yourself the victim of a thief. If so, you might call on the gods for justice, as the large haul of curse tablets found in the spring in the baths at Bath attest.

The overall bathing ritual was a lot more involved than what we would think of a bath entailing today. For a start, washing — or at least getting clean — was only one aspect of the process: exercise and massage also played a part. So having taken off your clothes, you would normally be anointed with oil and then head off for some light exercise, such as a ball game. Having worked up a bit of a sweat, you would start the sensory journey through the sequence of rooms that made up the baths themselves. Although there was no set route, you might start, as Lucius does, with an exhilarating visit to the frigidarium (cold room), luxuriate in the tepidarium (warm room), and then move onto the caldarium (hot room), where you would sweat some more. At some point, your skin would be scraped with a strigil to remove the sweat, dirt and oil, and you might also have a massage. At the end of the process, if you were wealthy enough, you would be anointed with perfumes. For Lucius and his family the bathing process takes just over an hour but for those with time to spare, it could be a much more leisurely experience.

Left, a set of bronze strigils. Right, bronze statue of an athlete scraping his skin with a strigil. British Museum. Images: Paula Lock

Bath sandal from Vindolanda. Image: The Vindolanda Trust

The sensory experience provided by the baths was not just for the bathers, as Seneca — who lived above a bathhouse — reveals. He paints a vivid picture of the cacophony of sounds that would shatter his valued peace and quiet.

Exercise: You can immerse yourself in Seneca’s sensory experience here. As you read try to identify:

- What activities took place at the baths?

- What sounds was Seneca subjected to?

- What sort of smells might have wafted around the bathhouses?

Baths, women and children

When watching the film, you may have noticed that there were no women present in the baths with Lucius and his family. Although in the first century CE men and women bathed naked together (edicts were later issued to stop this practice), women could also choose to visit one of the older Republican baths. In these, bathing was segregated and separate facilities were provided for men and women. Alternatively, if separate facilities were not available, a designated time was appointed for women-only bathing.

It seems, from the evidence, that children younger than Lucius and his brother were also welcome at the baths. Three children’s teeth have been found in the baths at Caerleon in Wales, and it has also been suggested (by Koloski-Ostrow) that a drawing of stick men in the Sarno Baths in Pompeii was made by a waiting child. An inscription from Rome also attests to child bathers. Here, two freedpeople mourn the death of their eight-year-old son who drowned in the piscine of the Baths of Mars. CIL 6.16740

One text that deals with the management of the baths at Vipasca, an imperial mining facility, not only details the allotted time for male and female bathers, but also provides an interesting behind-the-scenes glimpse into the operations of a bathhouse.

Exercise: Study the text, Of the Management of the Baths, and note down:

- The opening hours of the baths and the times designated for male and female bathers;

- The duties that must be performed;

- The penalties incurred for not adhering to the rules.

Home and dinner

As well as being centres for cleanliness, the baths had a social function as they were often used as a meeting place for people planning to have dinner together afterwards. One downside of this arrangement was that those without dinner plans would use the baths as a venue to hunt down an invitation. Martial paints a picture of one particularly tiresome dinner-hunter who latches onto his victim until he finally gets the offer ‘come and dine’. Mart. 12.82

For the Secundus family, having completed their trip to the baths, they head off home for a well deserved dinner, refreshed, relaxed and smelling of sweet perfume.

Bibliography

Fagan, Garrett G. Bathing in Public in the Roman World. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1999.

Laurence, Ray. Roman Passions: A History of Pleasure in Imperial Rome. London; New York: Continuum, 2009. See Chapter 5, The Roman Body at the Baths.

Nielsen, Inge. Thermae et Balnea: The Architecture and Cultural Historyof Roman Public Baths. Aarhus: Aarhus University Press, 1990.

Yegül, Fikret K. Bathing in the Roman World. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2010.