‘Let me be read by a girl who warms to her betrothed’ (Ovid Amores 2.1.5).

The Lucius films have a strong focus on betrothal of teenage boys and younger girls by their fathers. Looking at the comments on YouTube, we’ve found that there are many people confusing the idea of Lucius being engaged to a 7 year old with the concept he would marry a 7 year old. Roman minimum age for marriage for girls was 12 years (interestingly it was fourteen years for males). What is so fascinating about the Romans is the idea in childhood that betrothal involved children of such different ages. This idea lies at the very heart of both films – a piece of research published by Mary Harlow of the University of Leicester and Ray Laurence of the University of Kent. In this blog, we connect you to the research behind the film on betrothal and to the key ancient sources on the subject.

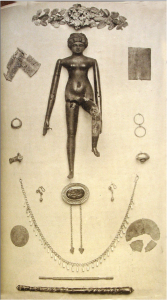

Betrothal was the announcement, or mutual promise, of marriage, underlying this announcement was agreement or consent to the betrothal. It needed to be agreed by the fathers of the children to be married, and the boy and girl also needed to give their consent. All parties needed to be old enough to understand what was being done and the nature of consent to marriage. The age of seven was picked out by lawyers as the minimum age for consent. Thus, in the film, you will have seen a seven year old girl becoming betrothed to a teenage Lucius. They would not have been able to legally marry until she was twelve – the minimum age for marriage in ancient Rome for girls. A key feature of betrothal was gift-giving that caused the girl to gain rings, jewels, ear-rings and so on. In this blog, some of the issues of age and gift giving are explained, and we provide the evidence from antiquity that provides us with the information lies at the heart of the Lucius films.

Gift Giving and Betrothal

Once betrothed, the girl was referred to as a sponsa and the boy as a sponsus. The gift of a finger ring by the sponsus to his sponsa occurred at this point and was regarded as a tradition stretching back in time. Numerous examples of these finger rings, that were betrothal gifts survive from antiquity. These tend feature images of joined hands (dextrarum iunctio), or the name of the sponsus, or a young man’s and young girl’s heads in profile facing each other. The range of gifts found in Roman law can include a farm, livestock, and slaves.

In Four Sisters in Ancient Rome, you will have seen the betrothed Domitia with all her jewels- this idea comes from Tertullian’s Apology (section 6)– a Christian Text that attacks the luxury of engagement-rings and all the gifts given to the sponsa by the sponsus. The film allowed us to visualise this text of Tertullian’s linked here – you need page 22. It is also worth taking a look at how Pliny in the first century AD saw the development of both finger rings and the wearing of the bulla by male children in The Natural History 33.4 (link here).

The practice of these gifts at betrothal can be found right across the empire, not just in the Mediterranean, but also in Britain) and in graves of women from the Rhineland There were other gifts to the future bride: necklaces, bejewelled net-caps, bracelets, highly ornate clothing, all of which may seen to constitute the insignia sponsalarium. The evidence for this comes from the life of the emperors known as the Two Maximini – the younger of whom is described as a truly beautiful young man – he died young at the age of 21 (though some said at the age of 18). He was engaged to Junia Fadilla and gave her the following: a necklace with 9 pearls, a hat with 11 emeralds, a bracelet with 4 saphires, and gowns with gold all over them. A link to this text so that you can read it for yourself is here. If you are doing Latin, take a look at how these words are translated.

What emerges is a young girl at puberty or at the approach to puberty receiving gifts that would mark her out as distinct from other girls – she was betrothed and the gifts symbolized the future relationship of marriage with her husband. The sponsa was marked out as still a virgin, but had entered a liminal stage in which she was neither a child nor a married woman.

Creperia Tryphena

A sarcophagus was discovered during the construction of the foundations for the the Palace of Justice, not far from the Vatican, in Rome over 100 years ago. The name of the dead person was inscribed on the sarcophagus: Creperia Tryphena; but inside was not just a body but also a whole series of items: amber pendants, a myrtle crown, combs, a ring with clasped hands and the male name Filetus, a hair net, a necklace and also a doll. What all this indicates is that Creperia Tryphena died at a time in her life when she was engaged to Filetus with her doll indicating that she was still a child. It is notable that Persius informs us that dolls were dedicated by girls on their wedding day in the shrine of the Lares in their parents’ house.

Exercise: Using Legal Sources for Social History: Betrothal

All the evidence for this comes from the Digest of Roman Law compiled by Justinian. You can review the evidence for yourself in this link to the Digest of Justinian 23.1. To do this, you need to use the link here to access an on-line library of Roman Law with the following instructions to locate the passage you want:

1) on left hand menus click on ’18 Lingua Anglica’ takes you to next page;

2) scroll down to ‘533 The Digest or Pandects of Justinian’ click on word Scott takes you to the next page;

3) click on Book 23

What you now have before you are a series of passages on betrothal quoted from earlier legal writings, but these give us all the information we needed for the film. Questions to think about whilst reading these texts:-

A) Can you identify the passages that provide us with information on ages of marriage and age of betrothal?

B) Who gave their consent to a betrothal?

C) How was a betrothal ended?

If you are curious about the nature of marriage and how it was legally defined by Roman lawyers, keep reading it is in section 2 of Book 23. However, before you leave this webpage, take a look at the arrangements for paying the dowry to girl’s family in section 3 – we may return to this question in a future blog. But it is worth remembering that part of the dowry is paid during the period of betrothal.

Exercise: Augustus and the Law on Marriage

The emperor Augustus discovered that many men would become betrothed to very young girls, so that they might void penalties associated with being unmarried. In consequence, he tightened things up to ensure betrothals did not last for years and insisted that betrothal should not last for more than two years – perhaps causing the youngest age of a girl to be betrothed to have been ten years. Examine the passage from Cassius Dio’s History of Rome book 54 – you need to scroll down to section 16. The matter of prizes for being married is discussed in the link on the page that takes you to a definition of the Augustan Marriage Laws that were enacted to incentivize marriage amongst the Roman upper-classes.

What about the teenager betrothed to a young girl?

The young adult, sponsus – often under the age of twenty-five, was prevented by the Lex Plaetoria from making firm business agreements prior to the age of twenty-five years (Cassius Dio 52.20). This was not a problem for sons subject to the power of their father, since the agreement over the dowry could be negotiated by the two patres familias. For sons, whose fathers’ had died, a tutor or guardian would have been involved in the ratification of the negotiation – if still a child. Yet within the arrangement of betrothal, financial agreements were to be made with his future father-in-law over the payment of the dowry associated with marriage of that man’s daughter. Take a look at the evidence from a fictional speech in 27 BC with regard to what age a person might hold a magistracy in Augustus’ ‘restored republic’. On this link you need to scroll down to section 20 – numbers are in red.

Exercise: finding Latin Tombstones of the Betrothed

There are some inscriptions set up on tombstones to betrothed girls, you can use this webpage to search for the word sponsa to discover where these tombstones were found in the Roman Empire and, if you have some Latin, have a go at translating the inscriptions. You could also search for the male betrothed using the word sponsus. If you search for both sponsa and sponsus – you will find an inscription set up by a sponsus to his dead sponsa – a betrothal that never led to a marriage.

The Betrothal of Cicero’s Daughter to Crassipes in 56 BC

The relationship between the two families created through the betrothal and expectation of marriage can be seen in through the linkages created by Cicero with this young man. Cicero threw the party two days after his daughter’s betrothal to Crassipes on 4 April 56 BC (Cicero Letters to Quintus 2.6.2). The party or sponsalia was a public occasion and one of the duties of a after the sponsalia on 6 April 56 BC, we find Crassipes and Cicero dining together again. Crassipes and Cicero would have been in their twenties and fifties respectively following the betrothal and marriage of Tullia, and we might suggest that the age difference may have caused a greater distance between the two men. The purpose of the sponsalia and subsequent dinner would seem to have been a form of male bonding, which made the relationship between the two men closer. For the future son-in-law, this may have been an intimidating experience conducted in public to display their new bond. Crassipes was Tullia’s second husband and we do not find in the evidence that we have anything like Cicero’s later expression of enthusiasm for her first husband Gaius Piso Frugi some ten years earlier.

The strength of the relationship between a son-in-law and a father-in-law ran alongside the continuing bond between a daughter and her father. Just as fathers were expected to control their daughters, they were expected to hold sway over their sons-in-law – a feature of marriage that did not always occur (Cicero Letters to Friends 3.10, Letters to Atticus5.6). Crassipes and Cicero were creating a bond during the period of betrothal in 56 BC that it was hoped would last through the marriage. In connection with this factor, we should note that Tullia’s previous husband, Calpurnius Piso Frugi, had been one of the group of key players behind Cicero’s recall from exile in the previous year, alongside: his brother-in-law – Atticus, his wife – Terentia, and his brother Quintus (Cicero Pro Sestio 54, De Domo sua.59). The social relationship between father-in-law and sons-in-law is played out in Cicero’s treatises On the Republic (De Republica) and on Friendship (De Amicitia), the sons-in-law of Laelius are attentive to the older man’s words regarding their social and political world of the later second century B.C.

Bibliography

Harlow, Mary and Laurence, Ray: Growing Up and Growing Old in Ancient Rome, Routledge 2002 – this link takes you to the book – check out page 58, where we discuss betrothal.

Harlow, Mary and Laurence, Ray: ‘Betrothal, Middle Childhood and the Life Course’, in L. Larrson-Lovén and A. Strömberg (eds) Ancient Marriage in Myth and Reality, CSP: Newcastle, pp.56-77 – 2010.

Harlow, Mary and Laurence, Ray: ‘De Amicitia: The Role of Age’, in Passages from Antiquity to the Middle Ages III: De Amicitia, Acta Instituti Romani Finlandiae 36, pp.21-32 – 2010.

Treggiari, Susan: Terentia, Tullia and Publilia, Routledge, 2007.