This month Catherine Hoggarth, a PhD student funded by the AHRC through CHASE at University of Kent, draws on her recent placement at Corinium Museum to discuss daily life of soliders on the edge of the Roman Empire.

Now that Lucius’ education is complete he may choose to become a military tribune, and as the video suggests this could mean commanding troops at the edge of the Empire. This included Britannia (Britain) which was added to the Roman empire by the emperor Claudius 30 years before (AD 43) and was still, as we learn from Tacitus, rather unsettled during Lucius’s lifetime.

Despite the resistance large Roman towns sprang up across Britain including Londinium (London), Camulodunum (Colchester), Verulamium (St Albans) and Aquae Sulis (Bath) but there were also lots of smaller military forts dotted around the country, defending strategically important areas and securing supply lines and communications. Fifty years before the creation of Hadrian’s wall, what would Lucius have encountered if he had travelled to one of the smaller forts, and what would everyday life be like? Was it all red skirts, sandals and plumed helmets and beating up the locals? Underneath the town of modern day Cirencester three tombstones and a multitude of artefacts provide a rather different image.

Image: http://insertmedia.office.microsoft.com

The town of Cirencester, in the South West of England, is best known as the site of the prosperous Roman town of Corinium Dobunnorum which began life in the late AD 70’s, but its Roman origins can be traced back a further thirty years to when a fort occupied the site; the final version of this fort is what Lucius would have encountered in AD 73. On his way to the fort he may have encountered the tombstones of the cavalrymen Genalis and Dannicus and a merchant called Philus. All three memorials were placed in an area adjacent to the Fosse Way, an ancient road on which the fort was situated, and which still runs as A and B roads today. All three tombstones have inscriptions which show they were not from Britain or from Italy but auxiliary soldiers, recruited from the one of Rome’s allied states (provinces); all three men had travelled to Britain from across Europe.

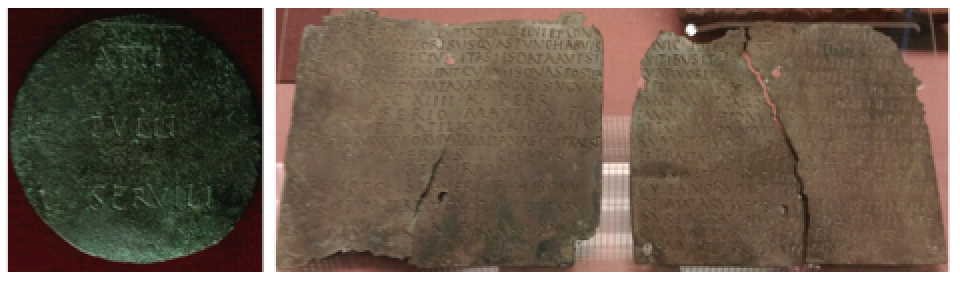

Images: Corinium Museum and Gloucester City Museum.

The full inscription for the tombstone of Sextus Valerius Genalis can be found here, he was a trooper of the Cavalry Regiment of Thracians, a Frisiavone tribesman (in the area east of Belgium, bordered by the Netherlands and Germany), he died when he was 40 years old after 20 years of service. Dannicus was a trooper of the Cavalry Regiment Indiana and a tribesman of the Raurici (who lived in the vicinity of the Western Alps on the boarder of Switzerland and France) who died after serving for 16 years; the full inscription can be found here.

Why would men from provinces who may have fought against Rome in the past want to join the Roman army? Aside from a job, the army offered many perks, clothing and feeding its recruits and offering them the chance, not just to travel and learn new skills but for social advancement. Auxiliary soldiers were also granted citizenship once they had completed 25 years, giving them enhanced legal status, tax exemptions and the knowledge that they could not be punished or put to death without a trial.

Images: Bronze Military Diploma’s which were worn, much like dog-tags, as proof of citizenship Corinium Museum and the British Museum, Catherine Hoggarth.

The tombstones of Genalis and Dannicus give an insight into what was important to both these men and how they identified themselves within the confines of the Roman military machine. They both chose a common design for an auxiliary cavalry tombstone; a horseman with spear or sword riding over the body of a prostrate enemy. Genalis is a standard bearer, a role of privilege within the army, he is decked out in the elaborate trappings of the hippika gymnasia (to which we will return to later) wearing rather splendid armour, with a large Medusa head in the centre of his breast plate, and a distinctive helmet which may have had a face visor. His horse is equipped with a multitude of buckles and harness mounts, all of which would both reflect light and make noise as the horse moved.

In contrast Dannicus tombstone is not as elaborate, but we can clearly see that his horse is equipped in a similar way. What stands out is his helmet or head decoration which is very different to that of Genalius, its worn decoration almost resembles a large flower. While these are idealised images they still demonstrate that the two men, while identifying with the Roman army, still saw themselves very differently. In much the same way that wearing a rugby or football shirt identifies a person as a fan of the sport, it is the colours and decoration which align them with a specific team. Neither man looked like a Roman legionnaire but they marked themselves out as both a part of and different to the main army with their equipment and dress.

We can also see this difference within the inscriptions on the tombstones. Despite not having completed 25 years of service Genialis had three part Roman name (a tria nomina) Sextus Valerius Genalis, which could indicate that he came from a tribe which had already received Roman citizenship or that his unit was enfranchised through valour on the battlefield; in contrast Dannicus displays only one name. Each man associated himself with his regiment and unit and with his home tribe; there is little doubt that these men felt a strong connection to the Roman army but their origins were still an important part of their identity. Both men joined units created outside their home provinces, travelled across Europe, and maybe even further and then died in yet another corner of the empire. We do not know if Genalis and Dannicus were ever at the fort at the same time but their daily lives would have followed a similar routine.

Roman camps and forts were built to adapt to the local terrain, but were often a playing card shape and included certain principle buildings such as the horrea (warehouses) and the principia (the forts headquarters) and the pretorium (commanders house) they also had central streets and large intervallum which was a space between the fort walls and the buildings/tents both to protect from missiles thrown over the walls and to allow the soldiers to form up within the camp and ride out ready for action. Kitchens and Latrines were set up around the walls for easy waste removal and to reduce the risk of fire.

Image: Houseteads Roman Fort, Catherine Hoggarth.

Large ditches were be dug around the camp area which in hostile territory, would be deeper with additional rather spiky defences. Marching camps used goat skin tents but during the winter months (the Roman army did not campaign during the winter when supplies were difficult to source and roads difficult to travel Vindolanda Tablet 343) or if a more permanent military presence was required, a more substantial wooden fort was erected; it was of course the soldiers themselves who undertook the building and ditch digging.

“…The hides which you write are at Cataractonium (Catterick, N. Yorkshire)…. I would have already been to collect them except that I did not care to injure the animals while the roads are bad..” Vindolanda Tablet 343

Genalis and Dannicus would have lived within the walls of a wooden fort at Cirencester and as Cavalrymen their horses would have been with them, both inside and outside the fort. Evidence from Wallsend and South Shields has shown a unit (turma) would be split into rooms of three or four men with their horses in the outward facing adjoining room. This would have ensured quick formation for the cavalry in the event of an attack, and also deepened the bond between the men and their horses.

There was no central mess or canteen for the soldiers but they received a daily ration of food which they cooked themselves. Locally produced food was supplemented from food shipped in from across the empire. Men also wrote home for luxuries to enhance their daily food and clothing needs. All lost or broken equipment had to be paid out of their wages so the men would mark their utensils, much as we do today with our lunch-boxes and mugs, so they could identify their own equipment.

Soldiers also bought their own kit and clothing, this was expensive and therefore well looked after and oft repaired, either by the soldiers themselves or by blacksmiths who travelled with the units. The copper Thames coolas helmet, now in the British Museum, survived long enough to bear the mark of four different owners. Apart from looking after themselves, the horses and the fort, daily patrols would have been sent out to scout the local area and remind the local population of the their presence. Communication was a vital part of the Roman army’s success, therefore the soldiers may also have been put to work building roads (which was unpopular and back breaking work) or relaying messages between the forts or towns.

The unit would also have spent a large part of their day training and drilling in order to maintain their fitness and to hone and develop their skills. Practice would have been on a parade ground (gyrus) much like the reconstructed one which can be seen at the Lunt fortress today. This training was important for developing a bond between the units and between the rider and horse. New recruits would also be drilled in full armour, running and jumping over wooden horses and using heavy wooden weapons to build stamina and muscle.

Image: ©2013-2017 JohnnyShumate

The Hippika gymnasia gave the men something to work towards, much like an equestrian team event today, the units would demonstrate their skills by competing against one another and showing their prowess in manoeuvring and throwing weapons at full gallop. This was watched and judged by senior officers and visitors and on occasion the emperor himself. The Lambaesis inscription details an address given by the emperor Hadrian to a cavalry unit referring to a military exercises he has observed:

‘You did everything according to the book. You filled the training ground with your wheelings, you threw spears not ungracefully, though with short and stiff spears.’

The decoration worn by both Genalis and Dannicus is suggestive of the finery worn during the games, though it has been argued that the decoration seen on both horse and rider could also have been used more regularly. As Ammianus Marcellinus recounts the bright bronze of the buckles and the armour which dazzled in the sun, alongside the jangling of decoration would have been a formidable and unnerving experience for any opposing forces. While the games were competitive and a source of pride for the units, they also ensured that the cavalry was a well trained and deadly fighting force.

Image: Plates and a pendant with coloured paint and fitting from a horse harness, Corinium Museum.

We have already seen that the auxiliary units identified themselves differently through their clothing but they also had practical considerations. A fragment of a cavalry tombstone shows the folded cuff of a long-sleeved tunic; men who had grown up in Gaul and Germania were used to the vagaries of the weather and sensibly adapted their clothing in order to deal with the British climate, adding long sleeves and trousers for warmth.

Relationships with the locals could be tense, we know from Juvenal Satires 16 that soldiers were used to a certain degree of legal protection which allowed them to intimidate the population (Vindolanda tablet 344). Despite this, upsetting the locals was not in the best interests of the Romans. Rebellions were costly and time consuming, as Nero found out, and local populations were needed to supply the army with food and extra men. The army was also accompanied by the soldiers families and the merchants and traders who made a living supplying their needs. A vicus (civilian settlement) would spring up near the fort attracting traders ready to serve the needs of the army. In their spare time the soldiers would head down to the vicus where they could drink, visit their families or play dice games and the traders could relieve the soldiers of their wages. Soldiers could not marry but women and children who accompanied them would live in the vicus, higher ranks were allowed wives within the fort as Tablet 291 from Vindolanda demonstrates. Some soldiers even choose to settle in Britannia with their families (as was the case in Gloucester, Colonia Nervia Glevum) rather than returning to a home they had not seen since they were young men.

Images: Bone dice from Corinium Museum and game boards from Rome, Catherine Hoggarth

The tombstone of Philus was likely to have been one such trader, he came from Sequanian (near Besançon, in eastern France). His tombstone maybe simple in comparison to those of the cavalrymen, but it links the army to the traders who also travelled to Britain to work and make a profit alongside a multitude of people from all parts of the empire. It was these, rather overlooked people, who ensured the success of the Roman occupation of Britannia, and the conversion of Cirencester’s early Roman fort into a successful town.

Some units would have continued to recruit from the provinces of their creation, but for units further from home replacements would have been sought through local recruitment. Over time the units would have represented a mixture of cultures and languages. The Roman army used Latin for all its administrative functions, it is argued that that soldiers would have had a rudimentary understanding of Latin and all three tombstones have Latin inscriptions. Regardless of origin and language the units functioned successfully and integrated men from across the empire. Literacy would have been a bonus within the army, men who could read and write were more likely to be promoted within the ranks. The same is true for the traders such as Philus who would have had to employ a scribe if he could not read or write himself (Vindolanda tablet 344 ).

Image: Appian Way, Catherine Hoggarth

In the end all three men were memoralised in stone, in a very Roman fashion, along a road where their image and details could be seen and read by a multitude of travellers, as the following tombstone inscription attests:

‘Stranger, this silent stone asks you to stop, while it reveals to you what he, whose shade it covers, entrusted it to show. Here are laid the bones of Aulus Granius the auctioneer, an honourable man of high trustworthiness. No more. This he wanted you to know. Farewell.’ Aulus Granius Stabilio, auctioneer, freedman of Marcus. Found at Rome. Latin Text

They could not have imagined they would be found two thousand years later and helped us to understand the multicultural army which set up home in Britannia in the middle of the first century AD.

Bibliography and further reading:

Bidwell, P. T. (2007). Roman Forts in Britain. London: London : The History Press, English Heritage.

Bull, S. (2007). Triumphant Rider, The Lancaster Roman Cavalry Tombstone. Lancaster: Lancaster: Palatine Books, Carnegie Publishing Ltd.

Dixon, K. (. R. (1992). The Roman Cavalry : From the First to the Third Century AD. London: London : Batsford.

Goldsworthy, A. (2003). The Complete Roman Army. London: London : Thames & Hudson.

Hodgson, N. and Bidwell, P. T. (2004). Auxiliary Barracks in a New Light: Recent Discoveries on Hadrian’s Wall. Britannia, 35, 121-157.

Holbrook, N. (1998). Cirencester : The Roman Town Defences, Public Buildings and Shops. Cirencester: Cirencester : Cotswold Archaeological Trust.

Holbrook, N. (2008). Excavations and Observations in Roman Cirencester 1998-2007. Cirencester: Cirencester: Cotswold Archaeological Trust.

Jones, R.H. (2012). Roman Camps in Britain. Stroud: Gloucestershire: Amberley Publishing.

Hyland, A. (1993). Training the Roman Cavalry : From Arrian’s Ars Tactica. London: London : Grange Books.

Hyland, A. (1990). Equus : The Horse in the Roman World. London: London : Batsford.

Shotter, D. (2007). Roman Britain. Abingdon: Oxon: Routledge.

Webster, G. (1988). Fortress into City : The Consolidation of Roman Britain, First Century AD. London: London : Batsford.

Wacher, J. & McWhirr, A. (1982). Early Roman Occupation at Cirencester, Cirencester Excavations I. Cirencester: Cirencester: Cotswold Archaeological Trust.