A Culture of Shaving

Grooming was fundamental for the creation of a Roman. Hair was cut and combed – it is one of the main features of statues of famous emperors. Like cleanliness obtained by going to the baths, grooming created by a barber was an essential element in what it was to be a Roman. It would appear that this applied to both males and females in ancient Rome.

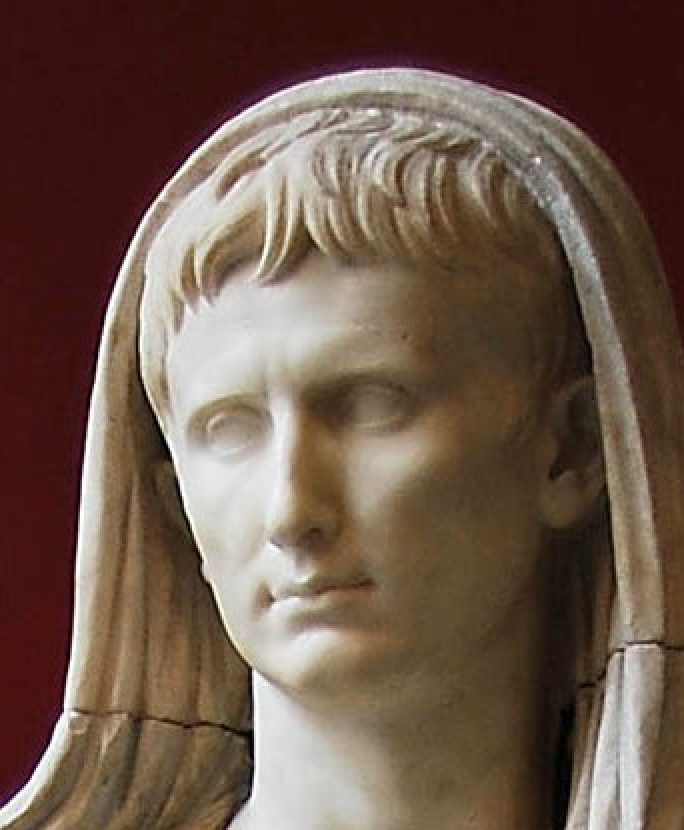

The emperor Augustus was one of those Romans, who shaved every day and paid special attention to his appearance, something that can be seen in the many statues that survive of Rome’s first emperor.

In the film, Four Sisters in Ancient Rome https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=RQMgLxVxsrw, you can spot the torturer going to the barber in the Subura early on in the film. This blog looks at the grooming of males, for the reason that most publications on hairdressing connect this Roman practice to female hair and, thus, omitting a major cultural practice. It might also be said that the favouring of female hairdressing may reflect our own social biases. Yet, it needs to be recognised that female hairstyles could be far more complex than those of males.

Hairstyle and hair-cutting is still associated with gender division today, leading one writer to call the Barbers’ Shop ‘the last male space’ http://www.spectator.co.uk/2013/08/the-last-male-space-why-old-fashioned-barbers-are-booming/. For female hairstyles in ancient Rome, see this film that introduces the subject https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1Ev5QIYOJyQ.

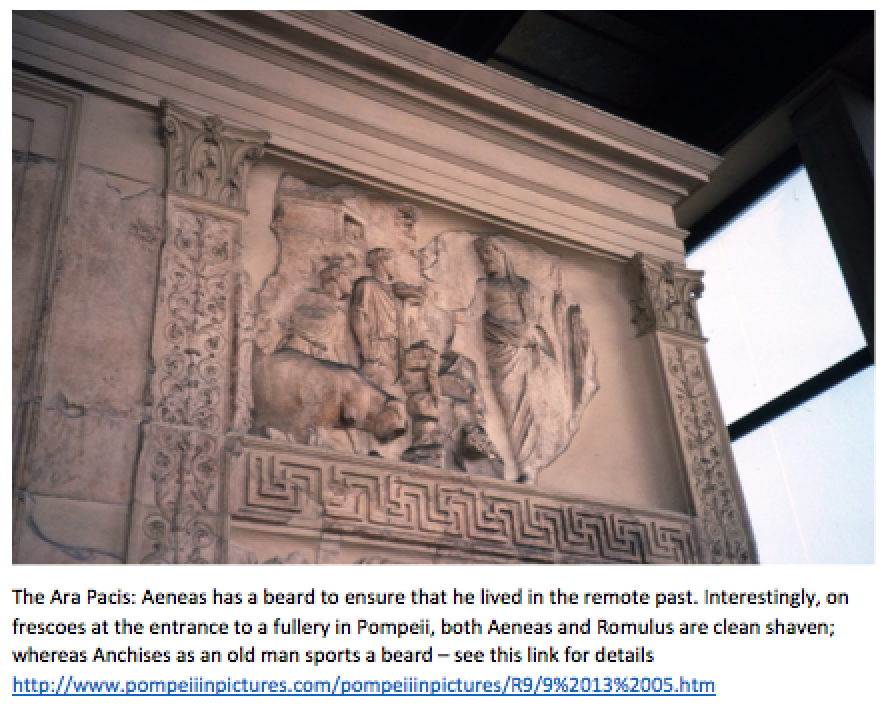

In ancient Rome, barbers had not always existed. Varro made this point clearly by observing its proof in the fact that very old statues featured beards and Pliny was to suggest that barbers were only introduced in 300 BC. Thus, our concept of the shaved Roman face did not stretch back into the myths of time and, as can be seen on the Ara Pacis in Rome – Aeneas had a beard. The contrast is striking with the images of Romans, such as Augustus, of whom Pliny the Elder (Natural History 7.211) never neglected the razor and shaved every day. A feature of Roman grooming that was traced back by Pliny to Scipio Aemilianus, who died in 129 BC. Like so much of what we see as typically Roman, shaving was introduced by barbers, Greeks, brought to Rome from Sicily.

Hairy Youths

Children took up their toga of adulthood, when they were between 14 and 16 years old, but their facial hair continued to set them apart from most adults. It seems apparent from a relatively small number of references (Ovid Tristia 4.10.58; Palatine Anthology 6.161) that young males did not shave and were associated with a downy beard until they were in their early twenties; when the first shaving of their beard was marked by a dedication of the hair to a goddess, such as by Nero to Jupiter (Petronius Satyrica 29; Suetonius, Nero 12; Censorinus On Birthdays 1.10).

There were in fact three types of young men, who could be defined by their facial hair:

- Those who had dedicated their first beard – such as Octavian who shaved his beard for the first time in 39 BC at the age of 23 years of age (Dio 48.34.3). It was convenient prior to this date to associate himself with the god without a beard – Apollo (other gods were characterised by their beards – Neptune’s was blue and Mercury’s was blond.

- Those who were growing their first beard – who were associated with a misdemeanours (Juvenal Satires 166) and were perhaps the runners or Luperci at the Lupercalia – Augustus insisted that they should not be inberbes (unbearded).

- Those who had smooth cheeks – one of whom we find in Apuleius’ Metamorphoses (9.22.5) as the miller’s lover – who was both an adulterer and sexually attractive to men.

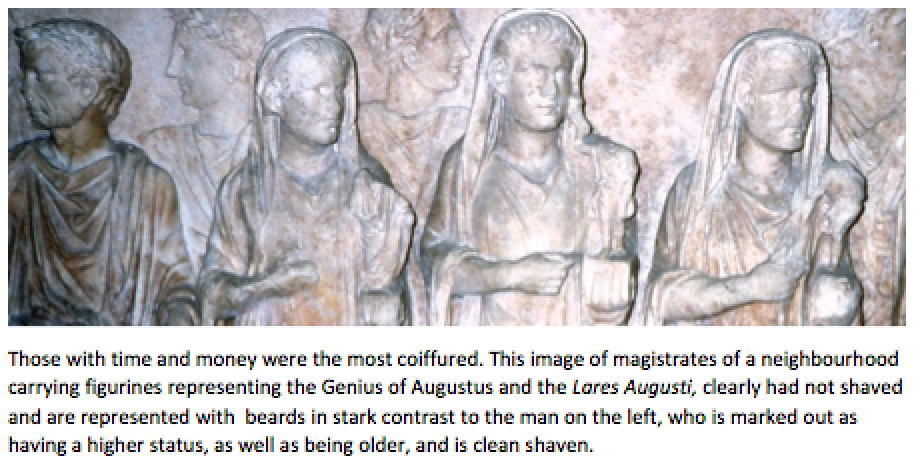

From Rustic Beard to Urban Grooming

Martial in quite a number of his Epigrams refers to hair, beards and grooming (e.g. 2.17, 9.27, 11.58, 12.59) that allow us to see the variation in Romaness from the visitor to Rome from the countryside with a beard to the fully groomed males of Rome – with their body hair carefully removed with tweezers. A feature that would produce some of the sounds recorded by Seneca (Letters 56) staying close to a bath-house. It allowed the Romans to also develop a contrast between their own culture of grooming and that of the Romans of the past, who had beards. Equally, the appearance of hair – groomed through to unclean was a clear marker of status.

Exercise: take a look at this short film to see what male hairstyle from the ancient world you find the most attractive https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=iYbJ7i8X47M

Exercise: take a look at this short film to see what male hairstyle from the ancient world you find the most attractive https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=iYbJ7i8X47M

Bad hair days and their meaning

In a society, where the appearance of the body was seen to reveal the state of mind of an individual – men grew beards and their hair, when they were in a deep crisis. Augustus, on hearing of the news of the defeat of Varus and loss of the legions in Germany, simply let his beard and hair grow for months – as well as famously bashing his head against a wall and shouting that Varus should give him back the lost legions (Suetonius Augustus 23). Similarly, when Caligula’s sister died, he also did not shave for days (Suetonius Caligula 24). Both Augustus and Caligula, by the appearance of their hair, showed their distress and appeared close to madness – something that is also found in the Aeneid (1.319 or 6.48)

Gender and hair care in ancient Rome

The tonsor or barber might work in the street or from a shop. They did not just cut hair and shave beards, but also trimmed finger and toe nails, removed unwanted body hair and made wigs. These seem very modern activities, but as Janet Stephens points out we need to avoid anachronisms and should not expect Roman hairdressing technologies to be the same as those found today.

The whole subject of ancient hairdressing is riven with complexity, not least because there was a whole technical language involving pins, needles, threads and so on. Interestingly, Varro (On the Latin Language 5.29.129) associates the words of hairdressing with a female toilet-sets (mundus). Yet, we know that males developed hair that was curled with similar equipment. Yet our sources, particularly Festus and Isidore of Seville, suggest that equipment was specifically for female hair that is associated with sewing with a needle and thread.

The gendering of the equipment is also matched by a Roman concept that fastidiousness over the body’s hair was a sign of effeminacy that is found at its most cutting in Martial’s Epigrams (e.g. 2.62). Yet, there was a fine line between being masculine and simply unkempt. Men might remove hair from their armpits, but regarded removing hair from their legs as a step towards effeminacy (Seneca Letters 114.4). Ovid in the Art of Love (1.505-524) offers advice to men don’t overdo the curling and avoid hairpins – this he sees as the grooming associated with women and effeminate men.

Instead, Ovid recommends that men make themselves attractive to women by ensuring that: their hair and beards should be trimmed by an experienced barber, their body should be bronzed from working out on the Campus Martius, their shoes should be the right size rather than too big, their toga should fit well and not be stained, their fingernails should be clean and not too long, hair should not protrude from their nostrils, teeth need to be free of plaque, their breadth should not smell, and their armpits should not smell like those of a goat. You have to wonder how many people in Rome did not do these things and were the inspiration for Ovid’s list of recommendations.

Exercise: can you use Ovid’s advice to see if Lucius and others followed this guidance in the film A Glimpse of Teenage Life in Ancient Rome? https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=juWYhMoDTN0

Further Reading

Elizabeth Bartman (2001) ‘Hair and the Artifice of Roman Female Adornment’, American Journal of Archaeology 105: 1-25.

John Englert and Timothy Long (1972) ‘Functions of Hair in Apuleius’ Metamorphoses’, Classical Journal 68.236-39.

Mary Harlow and Ray Laurence (2002) Growing Up and Growing Old in Ancient Rome: A Life Course Approach, Routledge: London pp.72-75. https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=aDvM81NIackC&pg=PA65&source=gbs_toc_r&cad=3#v=onepage&q&f=false

Martin Kilmer (1982) ‘Genital Phobia and Depilation’, Journal of Hellenic Studies 102: 104-112.

Janet Stephens (2008) ‘Ancient Roman Hairdressing: on (hair)pins and needles’, Journal of Roman Archaeology 21: 111-32.

Jerry Toner (2015) ‘Barbers, barbershops and searching for Roman popular culture’, Papers of the British School at Rome 83: 91-110.

Craig Williams (2010) Roman Homosexuality, 2nd edition, Oxford University Press, pages 139-144.