Part 2 of Life of a Slave in Ancient Rome continues to expand our understanding of this large group of people who were present in every aspect of life in Ancient Rome, but who are largely absent in the literature and archaeology that have survived. This is what ancient sources do tell us about Roman slaves:

Contents

Treatment

How slaves were treated depended largely on their master and his attitude to slaves. Columella, in his Res Rusticae, a type of handbook on farming, advises owners on how to treat their agricultural slaves including the clothing they should be provided with and how to achieve the greatest amount of labour from slaves while being as just as possible so that the slaves do not find their lives so difficult that they would wish to rebel.

Columella

In the care and clothing of the slave household he should have an eye to usefulness rather than appearance, taking care to keep them fortified against wind, cold, and rain, all of which are warded off with long-sleeved leather tunics, garments of patchwork, or hooded cloaks. If this be done, no weather is so unbearable but that some work may be done in the open.

(Columella, Res Rusticae, 1.8.9, click for link)

There is, moreover, no better way of keeping watch over even the most worthless of men than the strict enforcement of labour, the requirement that the proper tasks be performed and that the overseer be present at all times; for in that case the foremen in charge of the several operations are zealous in carrying out their duties, and the others, after their fatiguing toil, will turn their attention to rest and sleep rather than to dissipation.

(Columella, Res Rusticae, 1.8.11, click for link )

Nowadays I make it a practice to call [the slaves] into consultation on any new work, as if they were more experienced, and to discover by this means what sort of ability is possessed by each of them and how intelligent he is. Furthermore, I observe that they are more willing to set about a piece of work on which they think that their opinions have been asked and their advice followed… In addition he should give them frequent opportunities for making complaint against those persons who treat them cruelly or dishonestly. In fact, I now and then avenge those who have just cause for grievance, as well as punish those who incite the slaves to revolt, or who slander their taskmasters; and, on the other hand, I reward those who conduct themselves with energy and diligence. To women, too, who are unusually prolific, and who ought to be rewarded for the bearing of a certain number of offspring, I have granted exemption from work and sometimes even freedom after they had reared many children. For to a mother of three sons exemption from work was granted; to a mother of more her freedom as well.

(Columella, Res Rusticae, 1.8.15, click for link )

Many slaves were not fortunate enough to have a level-headed master such as Columella describes. Ancient philosopher and writer Seneca (1st century AD) provides several examples of the cruelty and injustice that slaves endured while he councils staying within ‘reasonable’ limits in the physical punishment of slaves.

Seneca

It is creditable to a man to keep within reasonable bounds in his treatment of his slaves. Even in the case of a human chattel one ought to consider, not how much one can torture him with impunity, but how far such treatment is permitted by natural goodness and justice, which prompts us to act kindly towards even prisoners of war and slaves bought for a price (how much more towards free-born, respectable gentlemen?), and not to treat them with scornful brutality as human chattels, but as persons somewhat below ourselves in station, who have been placed under our protection rather than assigned to us as servants. Slaves are allowed to run and take sanctuary at the statue of a god, though the laws allows a slave to be ill-treated to any extent, there are nevertheless some things which the common laws of life forbid us to do to a human being. Who does not hate Vedius Pollio more even than his own slaves did, because he used to fatten his lampreys with human blood, and ordered those who had offended him in any way to be cast into his fish-pond, or rather snake-pond? That man deserved to die a thousand deaths, both for throwing his slaves to be devoured by the lampreys which he himself meant to eat, and for keeping lampreys that he might feed them in such a fashion. Cruel masters are pointed at with disgust in all parts of the city, and are hated and loathed; the wrong-doings of kings are enacted on a wider theatre: their shame and unpopularity endures for ages.

(Seneca, Clem. 1.18.2, click for link)

Seneca despises those who are cruel to their slaves, but physician Galen (2nd century) has a different message in his discussion on cruelty. What does Galen criticise in the following passage?

Galen

When I was a young man I imposed upon myself an injunction which I have observed through my whole life, namely, never to strike any slave of my household with my hand. My father practiced this same restraint. Many were the friends he reproved when they had bruised a tendon while striking their slaves in the teeth; he told them that they deserved to have a stroke and die in the fit of passion which had come upon them. They could have waited a little while, he said, and used a rod or whip to inflict as many blows as they wished and to accomplish the act with reflection. Other men, however, not only (strike) with their fists but kick and gouge out the eyes and stab with a stylus when they happen to have one in their hands. I saw a man, in his anger, strike a slave in the eye with a reed pen. The Emperor Hadrian, they say, struck one of his slaves in the eye with a stylus; and when he learned that the man had lost his eye because of this wound, he summoned the slave and allowed him to ask for a gift which would be equal to his pain and loss. When the slave who had suffered the loss remained silent, Hadrian again asked him to speak up and ask for whatever he might wish. But he asked for nothing else but another eye. For what gift could match in value the eye which had been destroyed?

(Galen, On Passions and Errors of the Soul, trans. Paul W. Harkins, p. 38-9, click for link)

Galen writes that a master may strike a slave with a whip or rod as many times as he likes, as long as he has reflected first. To use a hand or an everyday object such as a stylus to punish a slave means the master has acted out of anger. Galen’s advice is to not beat a slave out of anger, but to inflict punishment calmly. Galen therefore, does not have the moral objections that Seneca has to physically harming slaves.

Villa Romana del Casale mosaic, Sicily

Rebellion

You have as many enemies as you have slaves.

-Roman proverb

As this Roman proverb indicates, Romans were in constant fear of their slaves. They were after all, enslaved people who were present in every part of their masters’ lives. They lived in their homes, worked their fields, and existed in large numbers throughout the city. Seneca tells us that once a proposal was put before the senate to dress all slaves in the same way. This proposal was turned down as the senate feared slaves recognising how great their numbers were (Seneca, de Clem. 1.24). The fear was well-founded as ancient sources demonstrate through tales of slaves murdering their masters and of large groups of slaves rising up in rebellion.

Tacitus

..the city prefect, Pedanius Secundus, was murdered by one of his own slaves; either because he had been refused emancipation after Pedanius had agreed to the price, or because he had contracted a passion for a catamite*, and declined to tolerate the rivalry of his owner. Be that as it may, when the whole of the domestics who had been resident under the same roof ought, in accordance with the old custom, to have been led to execution, the rapid assembly of the populace, bent on protecting so many innocent lives, brought matters to the point of sedition, and the senate house was besieged.

(Tacitus, Ann. 14.42.2, click for link)

*a boy kept for sexual purposes

To discourage slaves from conspiring to murder their masters a law was enacted that all slaves of a household would be tortured and executed if their master was murdered. This law motivated slaves to do all they could to prevent their master’s death.

Pliny

A shocking affair, worthy of more publicity than a letter can bestow, has befallen Largius Macedo, a man of praetorian rank, at the hands of his own slaves. He was known to be an overbearing and cruel master, and one who forgot — or rather remembered too keenly — that his own father had been a slave. He was bathing at his villa near Formiae, when he was suddenly surrounded by his slaves. One seized him by the throat, another struck him on the forehead, and others smote him in the chest, belly, and even — I am shocked to say — in the private parts… Macedo was kept alive for a few days and had the satisfaction of full vengeance before he died, for he exacted the same punishment while he still lived as is usually taken when the victim of a murder dies. You see the dangers, the affronts and insults we are exposed to, and no one can feel at all secure because he is an easy and mild-tempered master, for villainy not deliberation murders masters.

(Pliny, Letters, 3.14, click for link)

The Servile Wars:

Brutality and lack of control were cited as the conditions leading to the first major slave rebellion in c. 135 BCE:

Diodorus Siculus

Almost everyone as he got richer adopted first a luxurious, and then an arrogant and provocative pattern of behaviour As a result of these developments, slaves were coming to be treated worse and worse, and were correspondingly more and more alienated from their owners. …All men who owned a lot of land brought up their consignments of slaves to work their farms…some were bound with chains, some were worn out by the hard work they were given to do; they branded all of them with humiliating brand-marks. …The Sicilians who controlled all this wealth were competing in arrogance, greed and injustice with the Italians. Those Italians who owned a lot of slaves had accustomed their herdsmen to irresponsible behaviour to such an extent that instead of providing them with rations they encouraged them to rob.

(Diod. Sic. 34.2.26-27, trans. T. Wiedemann, click for link)

One of the greatest threats to Rome by a slave rebellion was the revolt of Sparticus, known as the Third Servile War. Depicted in the 1960’s Stanley Kubrick film, this story of Spartacus has survived through several sources, including that of Appian (2nd century).

Appian

Spartacus, a Thracian by birth, who had once served as a soldier with the Romans, but had since been a prisoner and sold for a gladiator, and was in the gladiatorial training-school at Capua, persuaded about seventy of his comrades to strike for their own freedom rather than for the amusement of spectators.

(Appian, The Civil Wars 1.14.115, click for link)

This war, so formidable to the Romans (although ridiculed and despised in the beginning, as being merely the work of gladiators), had now lasted three years.

(Appian, The Civil Wars 1.14.118, click for link)

[The slaves] all perished except 6000, who were captured and crucified along the whole road from Capua to Rome (The Via Appia).

(Appian, The Civil Wars 1.14.120, click for link)

Read more ancient sources on Spartacus here

The Romans reacted harshly towards the surviving slaves to ensure that slaves would not rebel again. The Via Appia from Capua to Rome is about 121 miles. To crucify 6000 slaves along this road it would be necessary to place a cross every two metres. For those travelling along the road it would have been a terrible sight and an effective warning to slaves.

Image source (click here)

Inscription: I have run away; hold me. When you shall have returned me to my master, Zoninus, you will receive a gold coin.

If a slave could not remove this collar the motivation of payment would turn any person into a slave catcher – willing to turn the runaway slave over to his or her master for the reward.

Although slaves were punished and means were taken to prevent them from running away, slaves still tried to find freedom in this way. Epictetus, a former slave, writes mockingly to someone who acts like a runaway slave who needs to find food while on the run.

Epictetus

ARE not you ashamed to be more fearful and mean-spirited than fugitive slaves? To what estates, to what servants, do they trust, when they run away and leave their masters? Do they not, after carrying off a little with them for the first days, travel over land and sea, contriving first one, then another method of getting food? And what fugitive ever died of hunger? But you tremble, and lie awake at night, for fear you should want necessaries. Foolish man! are you so blind? Do not you see the way whither the want of necessaries leads.

(Epictetus, 3.26.1, click for link)

According to Epictetus, we can assume that fugitive slaves were successful in finding food, as well as travelling over land and sea, presumably to freedom.

Holidays:

How is it possible to have a day off from being a slave? This is a valid question, but for the Romans it was thought to be possible. Generally slaves were considered to defile or pollute religious or ceremonial holidays, but there were certain ones in which they were able to participate. These were the Matronalia on 1 March, the festival of Fors Fortuna on 24 June, the Saturnalia from 17-23 December and the Compitalia from the 3-5 January (Bradley, 40). Dionysius describes the rites of the Compitalia festival in the following text. According to Dionysius, why did the Romans allow slaves to celebrate this holiday?

Dionysius of Halicarnassus

After this he commanded that there should be erected in every street by the inhabitants of the neighbourhood chapels to heroes whose statues stood in front of the houses, and he made a law that sacrifices should be performed to them every year, each family contributing a honey-cake. He directed also that the persons attending and assisting those who performed the sacrifices at these shrines on behalf of the neighbourhood should not be free men, but slaves, the ministry of servants being looked upon as pleasing to the heroes. This festival the Romans still continued to celebrate even in my day in the most solemn and sumptuous manner a few days after the Saturnalia, calling it the Compitalia, after the streets; for compiti, is their name for streets. And they still observe the ancient custom in connexion with those sacrifices, propitiating the heroes by the ministry of their servants, and during these days removing every badge of their servitude, in order that the slaves, being softened by this instance of humanity, which has something great and solemn about it, may make themselves more agreeable to their masters and be less sensible of the severity of their condition.

(Dion Hal. 4.14.3-4, click for link)

Freedom

In Roman society there were, as we have seen, only free citizens and slaves. There was also a category of people known as freedmen. This status was for former slaves who had been granted their freedom. The presence of these freedmen meant slaves had a real hope of one day achieving their freedom. Freedom was granted for many reasons. Pliny for example, explains that he grants freedom to any slave who is on the point of death.

Pliny

I have been much distressed by illness among my servants, the deaths, too, of some of the younger men. Two facts console me somewhat, though inadequately in trouble like this: I am always ready to grant my slaves their freedom, so I don’t feel their death is so untimely when they die free men, and I allow even those who remain slaves to make a sort of will which I treat as legally binding. They set out their instructions and requests as they think fit, and I carry them out as if acting under orders. They can distribute their possessions and make any gifts and bequests they like, within the limits of the household: for the house provides a slave with a country and a sort of citizenship.

(Pliny, Letters, 8. XVI)

Pliny gives freedom to slaves on the point of death as a kind of mercy. To grant a person freedom only when they will have no opportunity to enjoy it does seem quite unjust, but Pliny’s good intentions are demonstrated by his will to carry out the dying wishes of his slaves. Slaves under law could have no possessions, as anything they had belonged to their master.

Epictetus

Epictetus, a former slave, presents the interesting perspective of the life of a slave after freedom. According to Epictetus, what happens to a slave once they become a freedman?

A slave wishes to be immediately set free. Think you it is because he is desirous to pay his fee [of manumission] to the officer? No, but because he fancies that, for want of acquiring his freedom, he has hitherto lived under restraint and unprosperously. “If I am once set free,” he says, “it is all prosperity; I care for no one; I can speak to all as being their equal and on a level with them. I go where I will, I come when and how I will.” He is at last made free, and presently having nowhere to eat he seeks whom he may flatter, with whom he may sup. He then either submits to the basest and most infamous degradation; and if he can obtain admission to some great man’s table, falls into a slavery much worse than the former; or perhaps, if the ignorant fellow should grow rich, he doats upon some girl, laments, and is unhappy, and wishes for slavery again. “For what harm did it do me? Another clothed me, another shod me, another fed me, another took care of me when I was sick. It was but in a few things, by way of return, I used to serve him. But now, miserable wretch! what do I suffer, in being a slave to many, instead of one! Yet, if I can be promoted to equestrian rank, I shall live in the utmost prosperity and happiness.” In order to obtain this, he first deservedly suffers; and as soon as he has obtained it, it is all the same again. “But, then,” he says, “if I do but get a military command, I shall be delivered from all my troubles.” He gets a military command. He suffers as much as the vilest rogue of a slave; and, nevertheless, he asks for a second command, and a third; and when he has put the finishing touch, and is made a senator, then he is a slave indeed. When he comes into the public assembly, it is then that he undergoes his finest and most splendid slavery.

(Epictetus, 4.1.40-58, click for link)

Dionysius of Halicarnassus

Dionysius tells of how the granting of freedom to slaves changed from the time of the Republic to the Empire. Why does he object to these freedmen becoming Roman citizens?

Now that I have come to this part of my narrative, I think it necessary to give an account of the customs which at that time prevailed among the Romans with regard to slaves…

Most of these slaves obtained their liberty as a free gift because of meritorious conduct, and this was the best kind of discharge from their masters; but a few paid a ransom raised by lawful and honest labour.

This, however, is not the case in our day, but things have come to such a state of confusion and the noble traditions of the Roman commonwealth have become so debased and sullied, that some who have made a fortune by robbery, housebreaking, prostitution and every other base means, purchase their freedom with the money so acquired and straightway are Romans. Others, who have been confidants and accomplices of their masters in poisonings, receive from them this favour as their reward. Some are freed in order that, when they have received the monthly allowance of corn – given by the public or some other largesse distributed by the men in power to the poor among the citizens, they may bring it to those who granted them their freedom. And others owe their freedom to the levity of their masters and to their vain thirst for popularity. I, at any rate, know of some who have allowed all their slaves to be freed after their death, in order that they might be called good men when they were dead and that many people might follow their biers wearing their liberty-caps; indeed, some of those taking part in these processions, as one might have heard from those who knew, have been malefactors just out of jail, who had committed crimes deserving of a thousand deaths. Most people, nevertheless, as they look upon these stains that can scarce be washed away from the city, are grieved and condemn the custom, looking upon it as unseemly that a dominant city which aspires to rule the whole world should make such men citizens.

(Dionysius of Halicarnassus, a teacher of rhetoric in the late first century BCE, History of Rome 4.24.5, click for link)

In a letter from Cicero (1st century BC) we learn that a former slave of the family, Tiro, was set free. Why was Tiro freed?

Cicero

In the matter of Tiro, my dear Marcus… you have done what gave me extreme pleasure, when you preferred that he whose position was so unworthy of him should be our friend rather than a slave.

(Cicero, Fam. XVI, 16, click for link)

Abandonment

At the time of Claudius (mid-1st century AD) a law was enacted to protect slaves from being abandoned when they were sick or elderly.

Suetonius

When certain men were exposing their sick and worn out slaves on the Island of Aesculapius because of the trouble of treating them, Claudius decreed that all such slaves were free, and that if they recovered, they should not return to the control of their master; but if anyone preferred to kill such a slave rather than to abandon him, he was liable to the charge of murder.

(Suet. Claudius, 25, click for link)

Island of Aesclipius

Elements of the model © 2008 The Regents of the University of California, © 2011 Université de Caen Basse-Normandie, © 2012 Frischer Consulting. All rights reserved. Image © 2012 Bernard Frischer (click for link)

Death

An eternal release from slavery was of course, death. Owners had a responsibility to bury their dead slaves, for purposes of hygiene, but were not required to cremate slaves as was the custom for Roman citizens. Slaves who died in Rome after being abandoned would have been buried in a mass grave at ‘Potter’s Field’ on the Esquiline Hill up until the area was covered over and turned into the Gardens of Maecenas in 74-78 BC. In the cemetery on the Esquiline Horace tells us that:

Once slaves paid to have the corpses of their fellows,

Cast from their narrow cells, brought here in a cheap box

(Horace, Sat. 1.8.28)

The desire of slaves to receive a decent burial led to the building of columbaria – underground tombs with niches in the walls where cremated remains were placed in urns. Three columbaria in Rome, known as the Vigna Codini, were used in the 1st and 2nd centuries AD and held the cremated remains of freedmen and slaves. It is unknown exactly how these columbarium were funded, whether by the slaves themselves or by their owners, but their existence demonstrates that some slaves at least, were able to obtain some dignity in death that they may never have had in life.

Funerary inscriptions to Roman slaves further show the regard some owners had for their slaves.

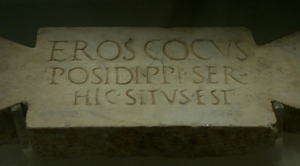

Inscription 1:

Baths of Diocletian, Rome (photo source: click here)

Latin inscription:

Eros, cocus Posidippi, ser(vus) hic situs est

Translation:

Eros, Posidippus’ cook, slave, lies here

Eros died a slave. His is only known by his first name – a name commonly given to slaves. His identity comes from having been owned by Posidippus and from his occupation. This inscription however, meant that he would not be forgotten by those who had known him.

Inscription 2:

photo source (click for link)

Funerary monument from Rome (c. 2nd century AD), currently in the Ashmolean Museum, Oxford.

The inscription reads:

Latin:

d(is) m(anibus) / L(ucio) Annaio Firm(—) / vixit annis ° V / m(ensibus) II . d(iebus) °VI . h(oris) ° VI ° /5 qui ° natus est / nonis °Iuliis / defunctus / est °IIII idus / Septembres /10Annaia Feru-/sa vernae su-/o karissimo

Translation :

To the spirits of the dead. For Lucius Annaius Firm(ius?), who lived 5 years, 2 months, 6 days, 6 hours, who was born on the 7th July and died on the 10th September. Annaia Ferusa set this up for her dearest household slave.

The mistress Annaia Ferusa calls Lucius a ‘household slave’, yet as the boy had three names, indicating he was a Roman citizen, it is likely that he died a freedman. Perhaps Lucius was freed just before death, as Pliny did for his slaves (see section: ‘Freedom’). The words of the text convey the strong affection of this mistress for her child-slave.

For Further Reading:

Bradley, Keith (1994) Slavery and Society at Rome, University of Cambridge, Cambridge

Joshel, Sandra R. (2010) Slavery in the Roman World, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge